Bumpkin Files

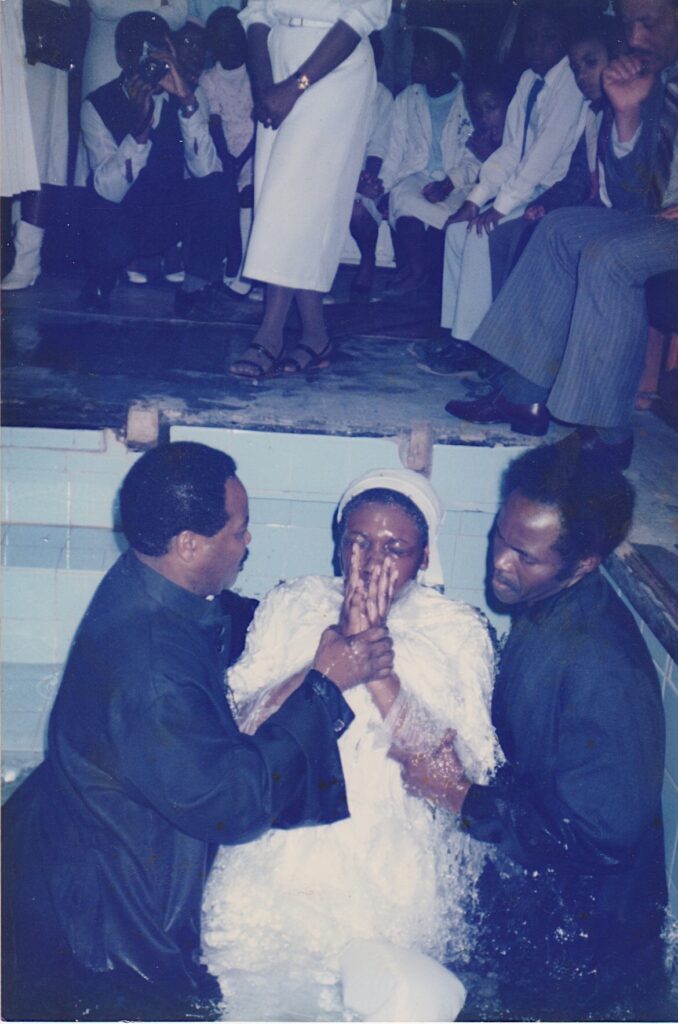

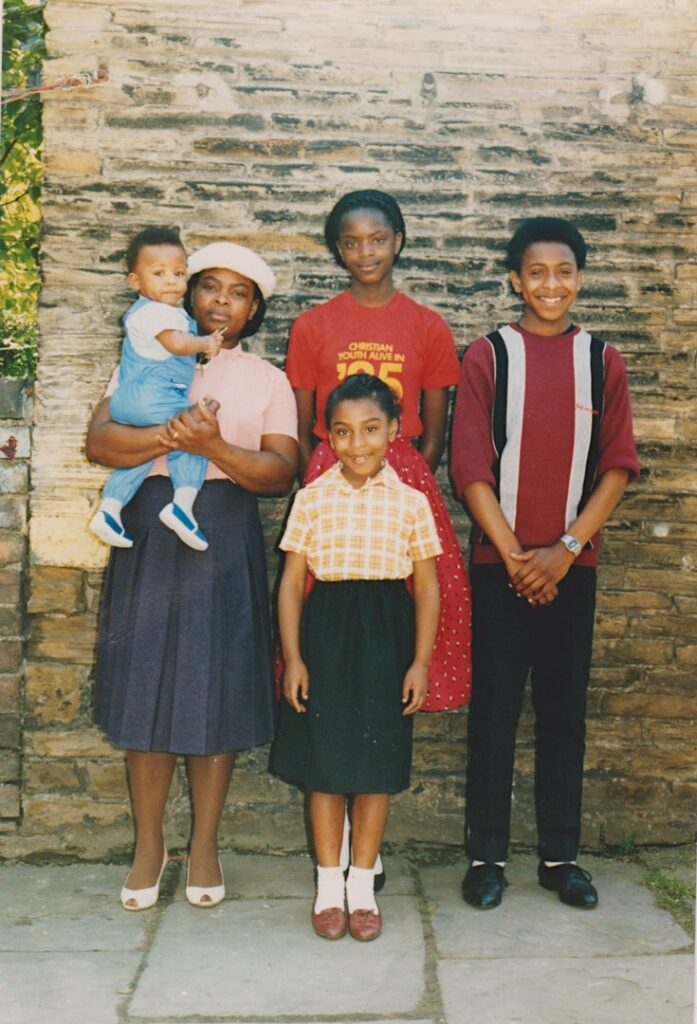

“I can smell the hot comb,” reads one of the comments on the Bumpkin Files Instagram page. It refers to an archive image of a wedding in Handsworth during 1968, taken by the godfather of Black British photography, Vanley Burke. The black-and-white photo sees a beautiful bride and her bridesmaids at the altar, all with expertly teased textured hair in elegant up-dos; the husband-to-be’s afro is picked out, round, high and proud. This snapshot, and the entire Bumpkin Files page, offer a time capsule to black British life beyond London. A quick scroll through archive photos reveals Leeds Carnival in 1969, photos of dashing Windrush gents in sharps suits in Essex, and even family photos of baby Jorja Smith in 1997.

The Bumpkin Files multi-media platform was founded by 25-year-old photographer Karis Beaumont in 2016 out of a very real desire to feel seen. From Hemel Hempstead in Hertfordshire, the photographer counts herself as one of the “Black Brits in the sticks” who felt distant from London-centric storytelling about black Britishness in black history documentaries and television programming.

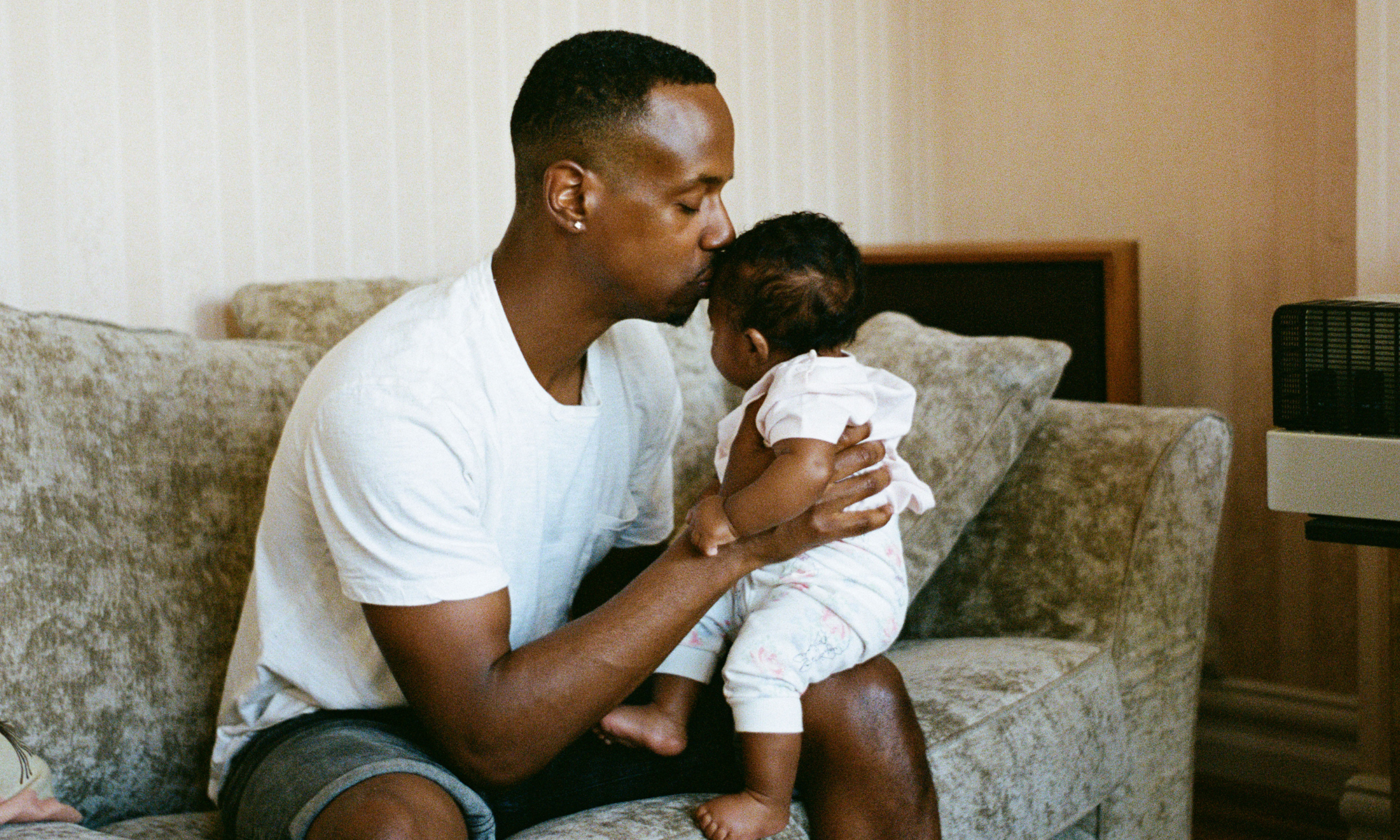

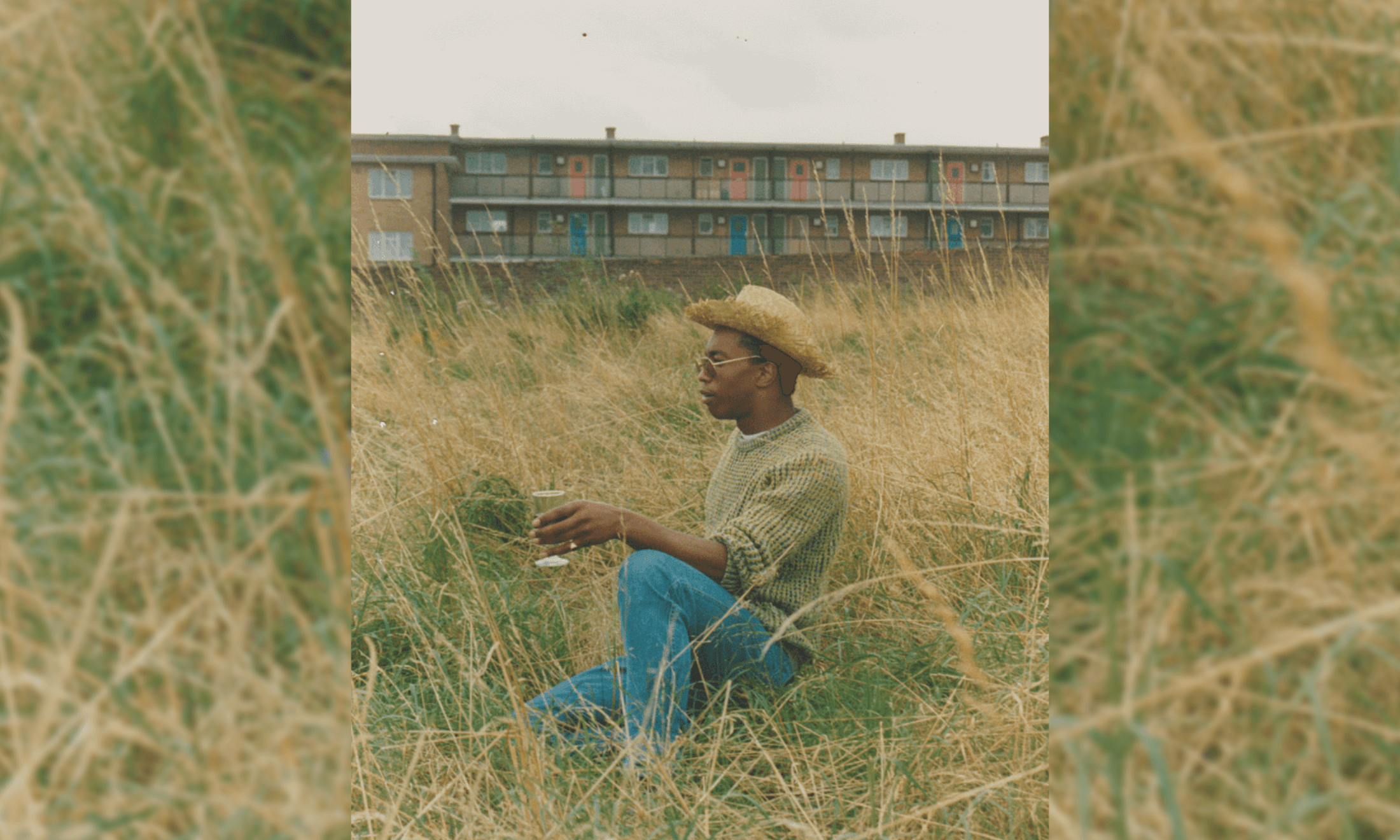

“I want to highlight the past, but make sure the present is acknowledged as well,” the photographer explains via Zoom, referring to her own photography project capturing black creatives who are thriving on their own turf against a backdrop of rural towns, as opposed to cityscapes.

Bumpkin Files performs a public service for a black Mancunian of Caribbean descent like myself. The photos taken in Manchester during the 1990s feel as if they could be from my parents’ photo album. It’s rare to see my own, very black, yet distinctly Northern, British history represented in this way.

Whether sourcing photos from 1960s Bristol or capturing burgeoning black talent from present-day Milton Keynes, for Karis, sharing stories of black Britishness outside of London offer an opportunity to deepen the connection of global diaspora.

gal-dem: Why did you start Bumpkin Files?

Karis Beaumont: I remember watching a documentary about pirate radio with my dad in 2016, and he’d share stories about tuning into [pirate radio] from St Albans, in Hertfordshire where he’s from. I’ve always liked watching documentaries about black British history but there was almost… not quite a void but something was missing. I couldn’t put my finger on it. After listening to my parents’ stories about their upbringing in different parts of Hertfordshire, the coin dropped. The thing that’s missing from black British storytelling is stories beyond London.

How did you find the images?

I first went back through my own family photo albums. Then I began to research whether I could access images of us in certain spaces and it was really hard to find. There were a couple of archives, like Black Cultural Archives and Black In The Day and I realised it was mainly [images from] London. So I scanned some of my pictures to see if I could contribute, then I decided to do my own thing. People responded on Instagram and sent in submissions.

What are your favourite photos from the archives?

I love looking at other people’s family photos. Our parents and grandparents were the original curators and the pictures would always bang! They were a lot more intentional with their photos, unlike now. Whether a disposable or film camera, they would shoot us at home or on holiday and then take the film to get developed. Our parents really put in the effort to conserve memories.

You describe yourself as “an image maker from the sticks” — did growing up in a small town help shape you artistically?

The one thing I hear from people is that my perception is refreshingly different. It [being outside of London] can be a positive. When you’re from a small town that doesn’t have as many resources as a big city, naturally you wander. I’ve always had wanderlust in travel but also in art, and music and I think that translates to my images.

Why is it important to shine a light on black British communities outside of the capital?

I want to stop [the] erasure. It can be easy to think that if the majority of the black community is in London, that you’ll barely see black people in the small towns and cities. But, black communities across the country are thriving. It may depend on where you go — sometimes there’s not really a hub — but by feeding into the narrative that there’s not many of us outside of the expected areas, it contributes to the erasure.

There are big and small stories from black people across the UK who have contributed to their societies, but unfortunately, we don’t acknowledge it or even know about it because commercially we don’t see it. It’s important that if [black people] want to do something different — just do it — because in the years to come it can form part of the cultural DNA of black Britain. Just do your thing, man.

Through your explorations with Bumpkin File, what have you learned?

The black community in Bristol did the work [via the Bristol Bus Boycott in1968] to ensure that anti-racist laws were in place. If it wasn’t for them we’d be in the gutter right now!

How do you hope audiences respond to your images?

I just want people to recognise that [black people] are thriving across the whole diaspora. I made sure to prioritise ‘us’ in my photos. It’s to the extent that I don’t even say, ‘I shoot black people.’ I simply say, ‘I shoot people,’ because, in my world, black people are the default.