Boxing and combat sports are and always have been working class. The phenomenon of “white collar boxing” is where people in “white collar jobs”, or middle class people, train specifically for charity bouts with little prior training to their fight prep. Novice fights that the fighter is sponsored for. The activity is considered so alien for middle class people to do that the novelty of it becomes a charity spectacle.

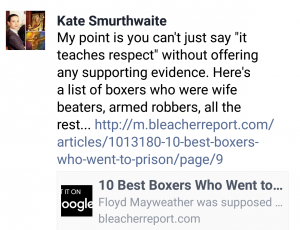

Following the deaths of both “white collar” boxer Lance Ferguson-Prayogg (an inquiry found his death to be attributed to fat-burning drug use in 2014) and then undefeated professional boxer Mike Towell in the UK, a new wave of internet vanguards against combat sports have emerged. For example, Kate Smurthwaite has used the deaths to push her article in the New Statesman, arguing relentlessly online for a case she has so little invested in.

The article reduces boxing to “effectively formalised pub brawls”, in total ignorance of the stamina, the delicate technique, the accuracy, the balance and the flexibility needed – every ingredient, every moment of research and training. The badly coded classist element of “pub brawls” hasn’t gone undetected either.

My favourite part of sparring isn’t the satisfaction in potentially hurting a training partner. It’s in playing the game, having a strategy, one upping one another technically using our newest techniques and ideas. We congratulate each other and laugh at the times we catch one another out. This involves a level of trust and compassion, a healthy level of competition and a genuine urge to help one another improve.

People do get hurt. We’re using our bodies to hit another body, but it’s with consent, with restraint, with training.

Statistically, where does boxing lie when it comes to fatality? Three runners have died running the London Marathon in the last four years. The chance of fatality when scuba diving is one in 34,400; when hand gliding it’s one in 560. Base jumping? One in 60. Four cyclists have died during the Tour de France. Seven FIFA associated players have died on the pitch in 2016 so far. 12 notable cricketers have died on the cricket pitch – the same number, globally, of professional boxers that have died in the ring due to head injuries.

In 2011, the National Safety Council (United States) found that when it came to the number of injuries in sport that required emergency hospital treatment, boxing came 26th. Bowling, cheerleading and tennis reported more injuries than boxing.

Smurthwaite has established false links between domestic violence, crime and boxers. Instead of discussing rampant rape culture, misogyny and racism in professional sports like football, cricket and any number of male dominated arenas, the writer’s insistence later online was that boxing was “violent” and therefore boxers must be violent toward women. This assumption erases the very existence of female fighters, and it uses the experience of abuse survivors like myself for baseless political points. Most worryingly, it is a clear reduction that “working class people hate women”, and through this, boxing has become code for working class.

When refusing to recognise a person’s right to train, to box, to fight, it’s key to look at why people fight, and what you’re trying to deny them. Any pretend concern for physical safety clearly isn’t the motivation for the hatred of boxing.

I started to learn and train Muay Thai in Reading two years ago under trainer and owner of Shaolin Tigers, Frank Bowen. I train consistently and frequently and help vulnerable people with self-defence. My relationship with violence is one which has always seen me on the exploited end. I don’t consider the physical empowerment of myself as a woman, a further chapter in my history as a victim of violence. It comes as directly the opposite.

Frustrated by the article and the continuous dismissal of women in combat sports, I spoke to two inspiring female fighters currently living in Thailand. Both are consistently showcasing other fighters and detailing their struggles, often motivating me in my training.

Emma Thomas – Writer, Muay Thai fighter, Thailand.

I’m a Muay Thai fighter, living in Thailand and training daily for the last four years. Before that, I was a shy 22-year old graduate with absolutely no experience of combat sports. In fact, I had pretty much no athletic ability or knowledge at all. When I first set my sights on training Muay Thai, I was apprehensive.

The hyper-masculine image of the sport that I’d been fed made me worried that I might not be welcome in the gym, or that no one would want me as a training partner. It took me over a year to push myself to do it.

Muay Thai opened up a whole new world for me. It gave me confidence that I’d never had before and showed me that I was capable of so much more than I’d previously thought. Still now, it has me on a continuous journey of self-improvement. That’s why I ended up fighting. With each fight, I grow, and that doesn’t just apply to my technique or power in the ring. It’s allowed me to build resilience and mental strength that has helped me elsewhere in life, too. Along with the many skills Muay Thai has helped me to forge, I’ve also had opportunities to create wonderful relationships with inspirational women who share my enthusiasm for the sport, which has been equally empowering.

While some may call Muay Thai “violent”, I wouldn’t agree. To me, it’s beautiful; not only in its aesthetic form but in how it challenges and changes those who make it their lives. I can’t count how many times I’ve been on the receiving end of jokes suggesting that people shouldn’t mess with me in case I punch them. These are usually coming from a good place, but show how not only how little understanding people have of what it means to be a fighter, but also how they connect combat sports with violence. To suggest that because I train to fight, I’d be likely to hit someone outside the ring, couldn’t be further from the truth. It’s almost insulting for a sport that has given me so much to be reduced to something so simple and derogatory.

Sylvie von Duuglas-Ittu, Muay Thai Fighter, Thailand.

“White Collar” participation is just now gaining momentum in Thailand, where Muay Thai is being advertised toward the middle class and, indeed, specifically women as a way of keeping fit. That’s a truly remarkable development from the working poor and farming roots of the sport. I find it encouraging and, as a woman, martial arts (western boxing included under that umbrella) have a tendency to empower the women who participate in them. If those women choose to do it for fitness, that’s great, just as men can have that same motivation. But dedicating oneself to fighting, to competition, is another thing entirely. It is a terrible thing when anyone is injured or worse, in any sport. But it is a terrible thing to cast away an entire category of art under the accusation of it being nothing more than violence, or entirely damaging and without merit. Ballet is beautiful to look at, but it does violent things to the bodies of dancers; and that’s beautiful, too. Training for the purpose of challenging yourself under the pressure of another trained opponent, so that you step into the ring with Intention versus Intention, is not the same thing as violence. And taking this artform away from the millions of people who have benefited from it, who live and love it, simply because you don’t understand it. Well, that does feel like violence.

I’ve been the victim of real violence, the kind that is intended for and carried out only with the will to harm. My experience with fighting is the exact opposite of that. Fighting has lessened my fear, has reduced my pain, has brought me greater compassion. I don’t need the people who watch my fights to know that at the moment they’re watching me in the ring, but there are very few fighters, I think, who haven’t tasted something like that for themselves.

—

Muay Thai has become an integral part of my life, and I can’t see myself not training. With Muay Thai however, an element of orientalism comes into play alongside the classism. The prayer, the folklore, the tradition and elements of respect (bowing to your gym and Kru’s, not dropping your hands when your teacher is speaking) are ignored and the sport is dismissed as brutal and foreign. This is a typical imperialist mindset, and fighters from around the world who actually train Muay Thai have nothing but respect and admiration for the sport and its origins.

Passing on to others, the empowerment that Muay Thai has given me is an amazing thing to be able to do. Shaolin Tigers is considering a women’s only class in 2017 should they find a space, and I’ve begun speaking with a Tae Kwon Do instructor in Oxford about working with them to organise Muslim women self defence classes with us too.

Learning to fight is a monumental power for our bodies, learning to defend ourselves is nothing short of a necessity.