How Drake gets away with being the biggest beg in music (and why I love him for it)

Varaidzo

06 Apr 2016

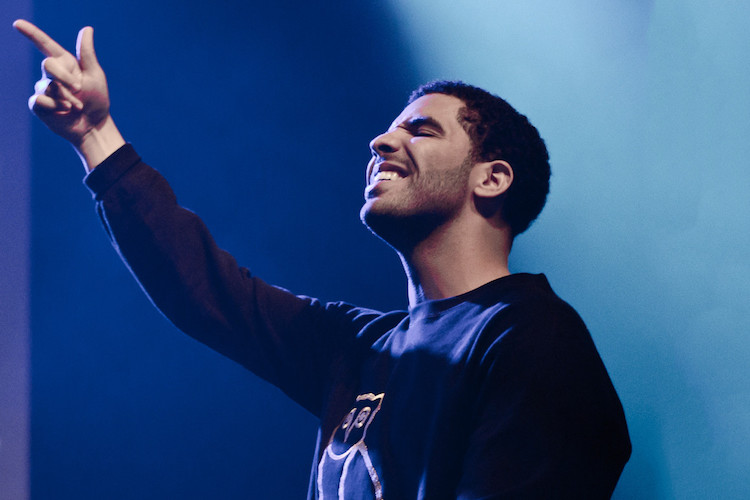

Drake is a beg. We know this. We’ve been knowing this. He’s a paradox that shouldn’t work: a Jewish black boy from the Toronto suburbs who went from being a sweet child star to one of the biggest rap stars of right now. He’s the same dude who rapped “we can stare up at the stars and put the Beatles on” on a song about f*ckin’ bad bitches. He dances like a dad, and inspired a series of cringe worthy memes that parody how his sensitive lyrics go “against the alpha male stereotype that is still prevalent in hip hop.”

Now, Drake has released a song called ‘One Dance’, where he’s crooning over the top of UK Funky House artists Crazy Cousinz production ‘Do You Mind’ by Kyla, a song so old in our British music scene that I was banging it when I was doing my GCSEs. You can imagine Drake in the studio, hearing the song for the first time, and nodding, wide-eyed, “Yes! This is funky!”

He’s embarrassing, man. Undeniably. Yet we love him all the same. It’s kind of a wonder we let him get away with it. Sure, he’s got a goofy smile and seems sweet enough for us to let it slide, but I have a theory that the reasons we let Drake get away with his begginess run much deeper. Reasons that are tied up in societies own complex relationship with race and identity, and further than that, our own. Bear with me.

Drake’s career started out in acting, on the teen show Degrassi. At the time, he was living between an affluent part of Toronto with his white mother, where he describes his experience of attending a Jewish high school by saying “the kids that were cool… I wasn’t really on their wavelength, which made me sorta uncool,” and his father’s in Memphis, where he was described as being “the furthest thing from the hood.”

When he made the decision to be a rapper, he entered into a musical culture rooted firmly in both blackness and repping your ends. There had never been a Canadian rapper that achieved Drake-level success before Drake, and Drake had no ties to historical hip-hop areas like New York, Chicago, California. Being mixed, his blackness was questioned too, “I’m so light that people are like ‘you’re white.’” he told the Village Voice.

Being in Degrassi, Drake was already known. People already assumed that they knew where he was from and what he was about. He had to prove that hip-hop was his art form too. Thus, he had to beg it:

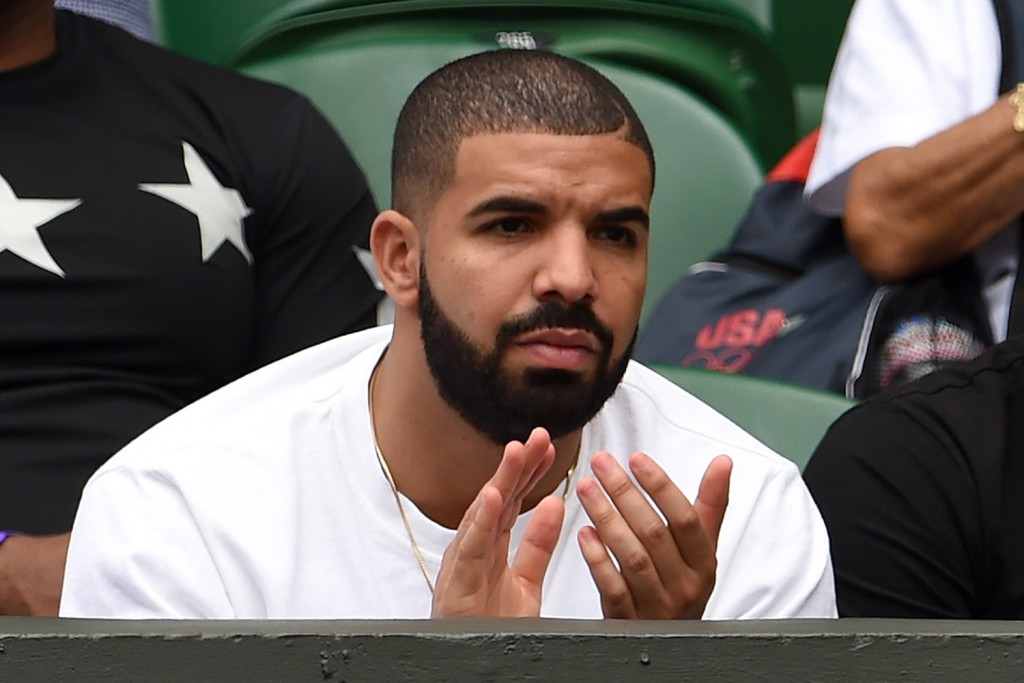

Source 1. Drake reps every sports team

In April 2014, SB Nation compiled a list of Drake’s sporting allegiances. Even they claim that his “allegiances are too far and wide” to create a comprehensive list, but it spans multiple sports, states, and even countries. And they weren’t the first to mention Drake’s sporting allegiances. In 2012, Drake tweeted to his critics, “I have friends on different teams. Proud of them today. Stop watching man so closely.”

In a similar way to hip hop, sports allegiance is rooted in where you’re from, and Drake’s allegiances are all over the place. Although he does support the Toronto Raptors, he transcends Toronto, and begs teams from everywhere. His transcendent nature replicates itself in his music too; we all know he’s a proud Canadian, but he transcends it, meaning that he can certify himself into hip-hop and specifically the US hip-hop scene without coming from an area historically associated with hip-hop.

Source 2. Drake’s ‘Scarborough Fever’

DRAKE ~ JUNGLE from October’s Very Own on Vimeo.

Before dropping If You’re Reading This It’s Too Late in early 2015, Drake dropped a mini-movie Jungle where he appeared with a Scarborough accent. He was then accused by Katie Heidl, a writer for Now Toronto, of, to paraphrase, begging it. “He’s sure as hell taken his appreciation to appropriation levels,” Heidl writes.

Scarborough is a far more diverse area of Toronto than the affluent Forest Hills where Drake grew up, and the Scarborough accent reflects that. “Breaking it down linguistically,” Heidl says, “would mean giving a huge credit to its West Indian background and heavy influx of Patois.” So, Drake was talking black, Heidl is insinuating. And he’s begging it, because he didn’t grow up in an area known for having black people living there.

It buys into the idea the blackness can be performed (or begged), and that Drake is mimicking this accent to prove his blackness, to prove that he has a place in hip-hop. But Heidl is a white woman, and as Kyrell Grant wrote back in an article entitled Sorry Music Journalists, Drake is Black, “that’s not a conversation with room for people outside of that culture to insert their voices.” Most importantly, Grant writes, “Trying to qualify or caveat his blackness because of his life experience… is a tactic that ignores the beauty and diversity of black experience and black people.”

So although, as Grant admits, there might be criticisms of Drake’s “use of the slang from a cultural heritage to which he may not have strong ties,” his blackness is not something we need him to beg. He’s black. He just is.

Source 3. The London Roadman

In July 2015, Drake came to London to play a set at Wireless festival. Around the same time, Twitter users began to point out that he was “trying to be a London roadman,” as Capital Xtra mentions in their photoset documenting the transformation. This included him using London slang, attempting to resurrect Channel 4 show Top Boy, a show set in London streets and featuring several British grime artists, and allegedly signing with grime label BBK (after getting them tatted on his shoulder).

Yeah, he was begging it hard. Trusss me daddi.

It’s not that Canadians can’t make grime, we’ve seen Canadian grime rapper Tre Mission freestyle with JME, but even he didn’t try and beg that he was from London as much as Drake. But grime and the black British rap scene is equally as rooted in black culture and stating your area as US hip-hop is, and this is just further proof of Drake’s ability to transcend the limits of where he’s from whilst still trying to beg that he’s from somewhere else.

So why does he do it? We all know where Drake is from, he’s always been honest about his upbringing. So perhaps Drake isn’t begging it at all, he’s just trying to prove that he can defy the limits we set on him.

When people like Kris Ex are writing pieces for Complex comparing him to Kendrick Lamar by stating Kendrick “is making music about the black experience, while Drake is kicking in the door by making black music for white people,” Drake can’t seemingly win. To be himself is already to be judged as begging it, as packaging his blackness for white palatability.

He is already being policed for where he’s from, for being a light-skinned black dude, for growing up with ties to more than one cultural sphere, all before he can claim these things as his own. And isn’t this a disjuncture that many of us from ethnically mixed families, or those growing up in the diaspora, also feel? The need to prove we are who we say who we are, when others continue to ask us where we’re really from, or deem us “not enough” of this or that.

And sometimes, in our hastiness to prove that our identity is ours, we beg it. We parody ourselves to show that we exist, that we are not always limited to one race, one nationality, one check-box on the census. We love Drake because he does this as well. And we let him get away with it because there’s nothing to get away with, not really. We can all be just a little bit beggy sometimes too.