Ning Yang

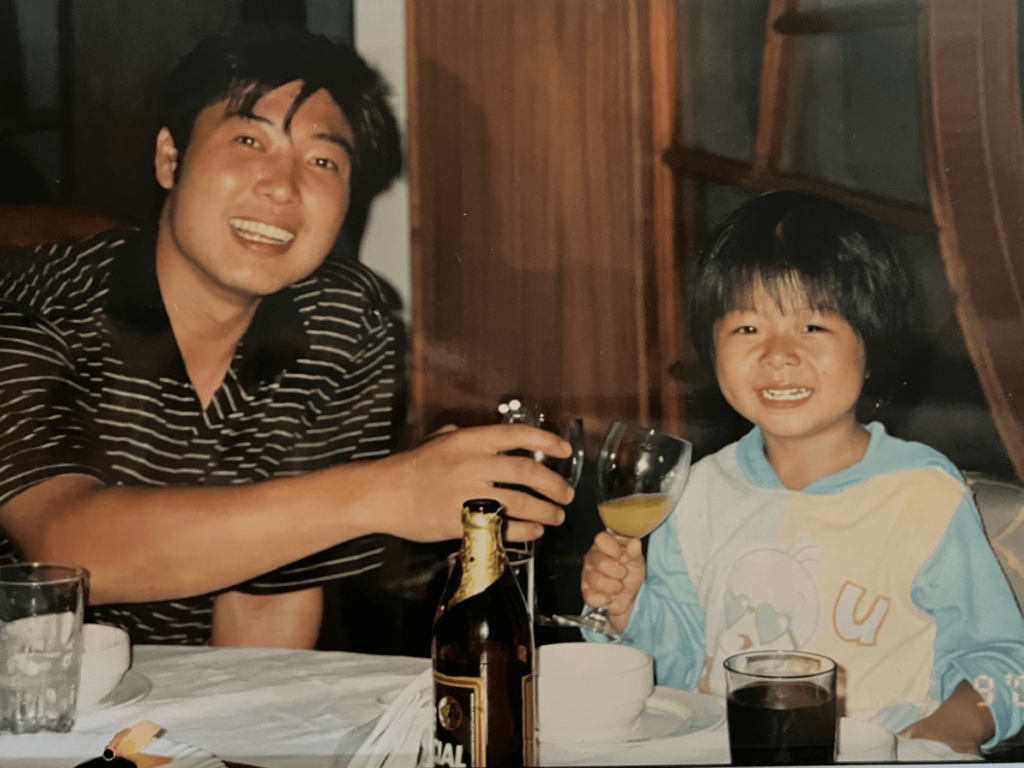

Growing up in Uganda as the only Asian person in my class, I did not feel Chinese at all. Except when I ate. Long before my mama and auntie taught me how to cook, they taught me how to eat – how to work my tongue around fish bones and spit them out delicately, how to suck the flesh from a prawn shell after ripping off its head, how to savour the gelatinous goodness of a fisheye. Otherwise, I did not think of myself as different to my friends. After all, we grew up together. Kampala was our city; Kam-pa-la – her name is a hymn of ascension that lifts us up in a symphony of rounded vowels.

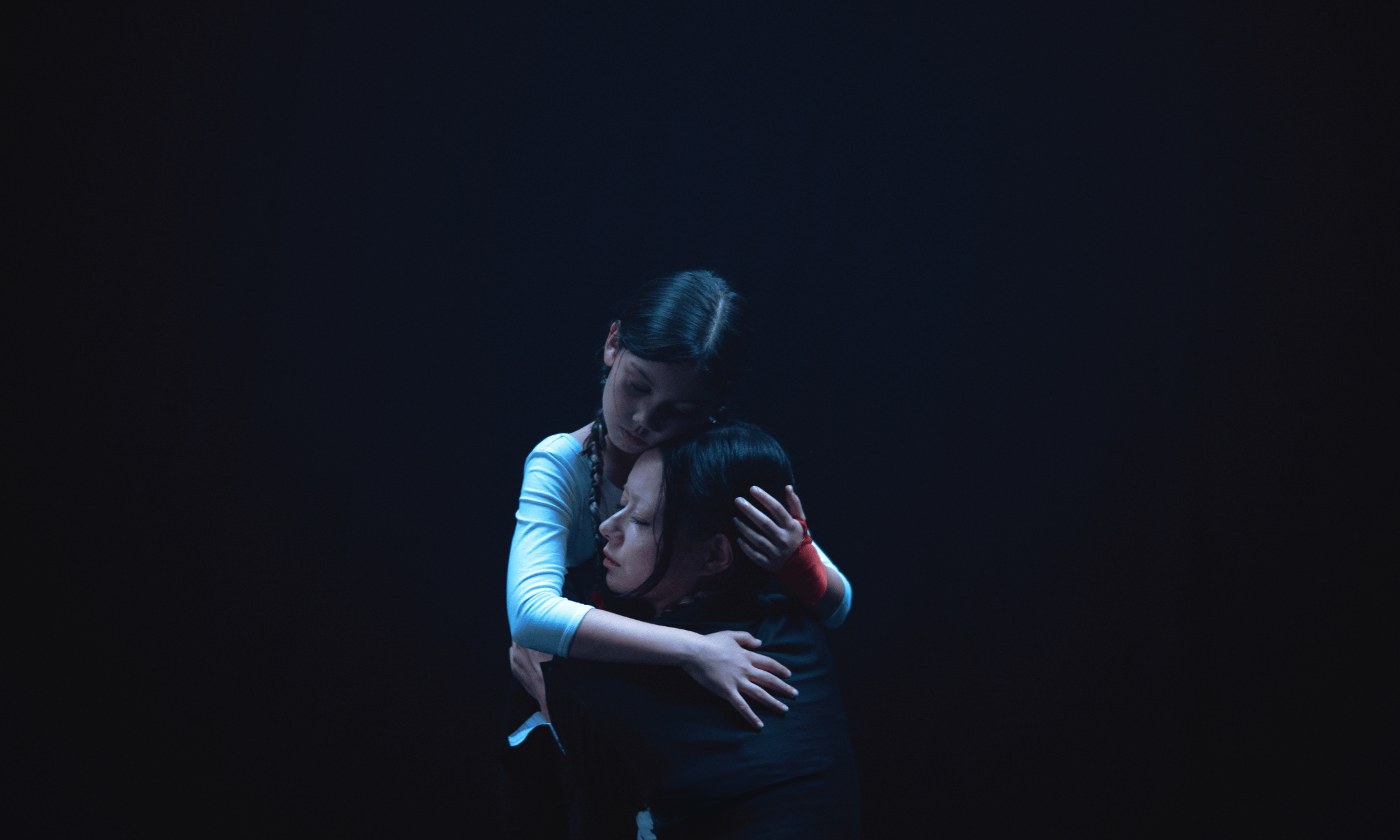

As I got older, I realised that it was not so easy to find a place to be, to feel at home. I wondered: where did my roots lie? My roots had overgrown their soil, overflowing into the sea, divided, bent and dispersed in every direction. My mama recognised this homelessness, this rootlessness within me without ever saying it in words. Instead, as all Asian mothers do, she spoke to me through the language of food.

“As all Asian mothers do, she spoke to me through the language of food”

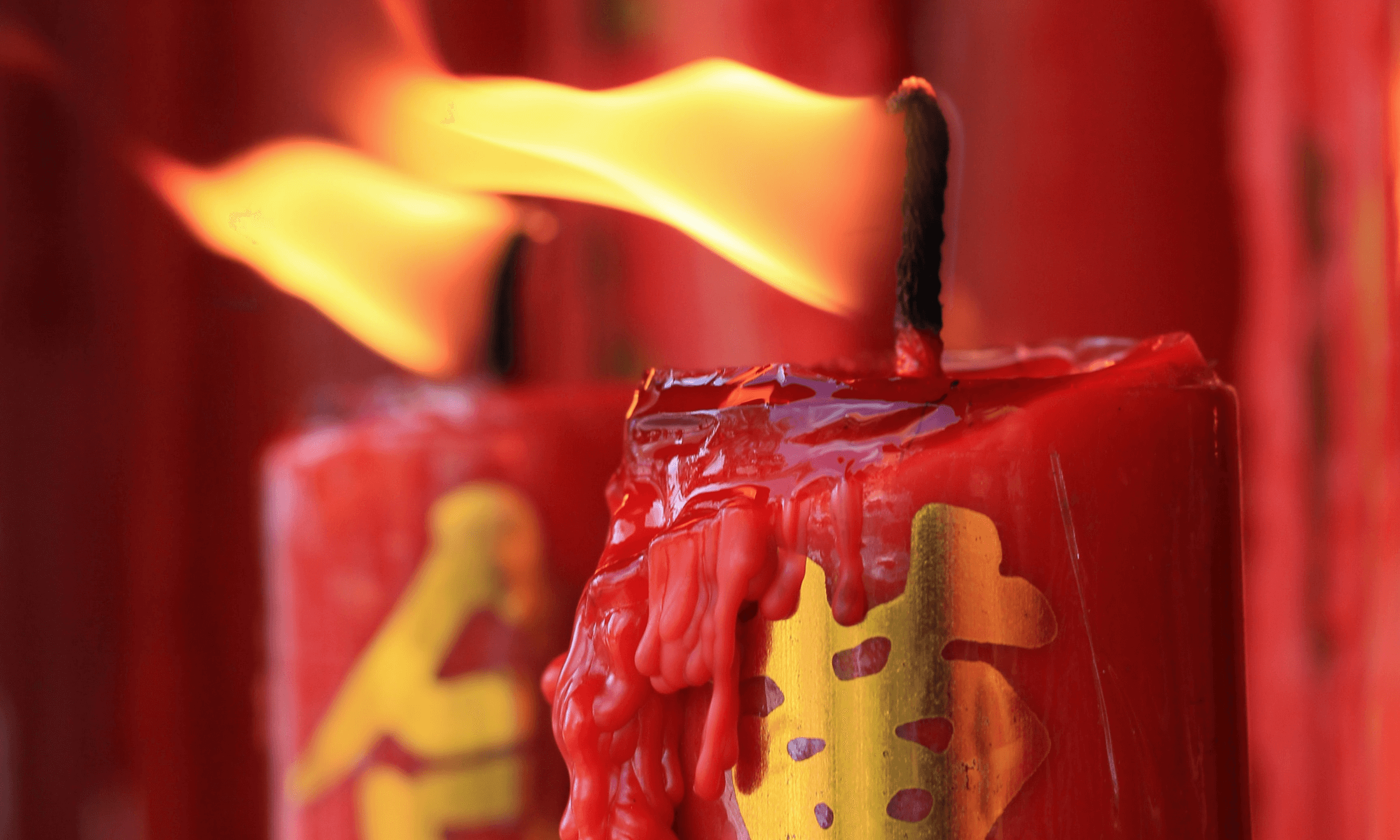

When I moved to the UK, 16 and alone, my bags were filled with zongzi – sticky rice parcels carefully enveloped in bamboo leaves, twirled into a cone with a little pork belly present hidden in the core of it all. This was my Mama’s way of remaking tenderness in a foreign land. Zongzi 粽子, composed of mi 米 and zong 宗, combines the word for rice with the word for ancestor. Zongzi was the gift our ancestors left us, mama would say. These sticky rice parcels are typically wrapped in bamboo leaves, but at home, in Uganda, there are no bamboos to be seen. There are only banana trees with clusters of leaves shaped like giant feathers – green, heavy and verdant. So that’s what we used – the banana leaves lovingly cut from our garden.

My mama’s hands fluttered like tiny wings amongst the leaves, holding my home and combining it with memories of her own. I watched her home take flight and land within her palm. She used to say,“the flavour of banana leaves is sweeter than that of bamboo, it tastes like sun. Funny how the taste of home changes, isn’t it?”

United within these little parcels was who I am and the history of where I came from – a reality that felt so disjointed most of the time. Unwrapping my mother’s 粽子, I could taste her history, I could imagine her following the flux of emigrants crossing the relentless oceans, mixing, melding with new places and slowly getting used to new tastes and foreign seasonings. I wondered how they would reshape themselves once more in my new home.

“When I moved to the white man’s land, food became a source of shame rather than one of discovery”

However, when I moved to the white man’s land, food became a source of shame rather than one of discovery. On one occasion where I suggested that we order chicken feet on a group outing to a Chinese restaurant, I could instantly see blue eyes becoming repulsed, turned away, I could almost hear their thoughts wandering, wondering if everything they heard was true. From then on, I was careful about who I expressed these pleasures to. I started imitating the habits of those around me, readjusting to the rules of the new dinner table. I thought to myself, yes, from now on, rather than our plate, it will be your plate and my plate; yes, from now on, meals will be neat and clean, unlike the dishes I’d eat at home, with claws and heads, skin and tails like it was still an animal. Keeping up this act meant I became a 生人, a stranger. A stranger to myself. The character 生 also translates to ‘raw’ and ‘uncooked’. Then, to be a stranger is to be part uncooked, to be cold, to be unknown and alone. After all, we live in and through our bodies.

As the pandemic spread throughout Europe in early 2021, I felt a sudden anxiety fill me, a slow all-encompassing dread. I could hear the news, I could almost hear people’s thoughts repeating ‘they eat rats’, ‘they eat bats’. Yet this time, something was different, the shame in me had shifted – perhaps it was the unabashed way in which the racism was repeated so loudly, recanted everywhere. It was so cliché all of a sudden, it became so apparent that they were abjecting us, demarcating a clean line between them and the Other. Well, if they are going to call us Other, I’m going to eat the whole concept of the Other, devour it plainly until the bones are chewed up, spat out, and all that is left is to see is the beauty of our existence.

When far away from home, it is often the taste of something familiar that reminds us not only of what we have eaten before but also of who we are. In Mandarin, to know is designated by the characters 熟悉, shuxi. Funnily enough, 熟 shu, is also the word for ‘ripe’ or ‘cooked’. Living alone in a place far away from home during lockdown, I was determined to cook myself back to knowing myself, to eat myself back.

“It is often the taste of something familiar that reminds us not only of what we have eaten before but also of who we are”

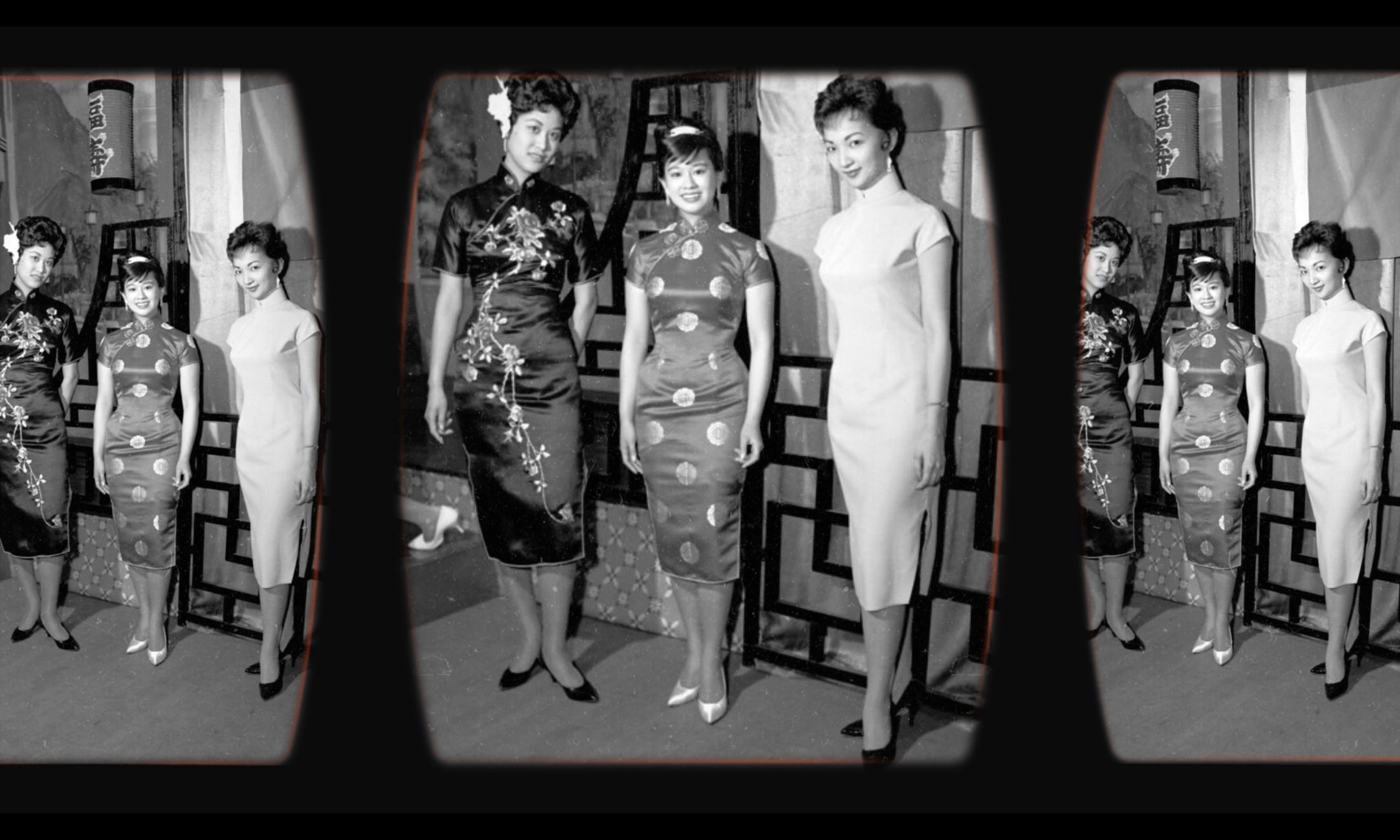

I spent hours on phone calls with my parents, bombarding them with incessant questions; “Mama, what is the best way to pleat the edges of a dumpling, how to I extract all of the pins-and-needles tingles from a Sichuan peppercorn, how do I blanche tripe and cook it to perfection, like you?” Recipes were interspersed with memories from their childhood, of flavours that brought back the past. Growing up during the Cultural Revolution, my mama said her hunger created fantasies. She remembered how her family, after a meal of plain rice, would sit down together and fantasize about the delicious dishes they’d had before, going into detail about the rare ingredients and the specific cooking methods. She said how my grandpa remembered the taste of a single drop of oil caressing his tongue. To eat, my grandpa told her, was to wage a successful war, to salvage food on barren lands. It was to attack food with rapacity and devour without remorse because it was uncertain when and from where their next meal would arrive. My grandma remembers people eating blades of grass, of neighbours becoming all skin and bones.

‘Discarding any part of an animal is a privilege that our communities couldn’t afford. Hunger was a given condition. When you take an animal’s life, you should thank it, eat it all, none of it should go to waste’, mama declared. Now, these undesirable offcuts of meat have become some of China’s finest luxuries. How beautiful is it that such desperation took something considered undesirable and turned it into a rarefied treasure? How does one turn chicken feet, a bony, fiddly thing, something almost devoid of meat, into a delicacy? As I take a bite out of a slow-cooked piece of chicken feet, soft and slippery, I can taste the strength of my grandpa, imagine how such a meagre piece of meat kept his hunger at bay. As my teeth work their way around the bones, I understand the toughness of his preservation, tasting the warmth of his resilience.