When it comes to reclaiming my black identity in Essex, I have my mum to thank. To the public, she’s known as Elsa James, a socio-political conceptual artist and activist whose work disrupts the negative and dated stereotypes of the ‘Essex girl’, making sure black women like myself aren’t written out of history. Representation of black women and marginalised communities is a common theme running through James’ work, but she has been rooting for better representation long before her professional career as an artist.

Growing up, I remember my mum would go out of her way to make sure I had black dolls that looked like me. I remember her reading me books about loving the colour of my skin and embracing the many different textures of afro hair. It wasn’t until later in life that I realised my mum had to order those books from America because you simply couldn’t get children’s books with that level of representation here in the UK.

“When it comes to reclaiming my black identity in Essex, I have my mum to thank”

I attended a very white secondary school and despite my mum’s efforts in the home, I still felt like I had an identity crisis as a teenager. Over the last few years, it’s been really affirming to my identity to see my mum take up space, from walking down the middle of Southend High Street in an elaborate red dress with her larger-than-life afro and gold crown, to her breathtaking live performance at Tate Britain with Black Blossoms this March. In 2022, she was named one of Essex’s 50 Most Influential People.

“The message is to just be unapologetically you,” she tells me as she burns a piece of Palo Santo wood in her cosy studio where we are sitting. The subtle sweet woody scent fills the room, which is covered in posters and pictures from her work and creative world. I’ve always felt like I’m stepping into her mind when I visit her studio. “I am unapologetically telling my story, our story and I’m not going to dilute it at all. If that disrupts or upsets then so be it. I’m going to tell the truth in my work in terms of histories that have been forgotten and stories that need to be remembered.”

“I am unapologetically telling my story, our story and I’m not going to dilute it at all”

Elsa James

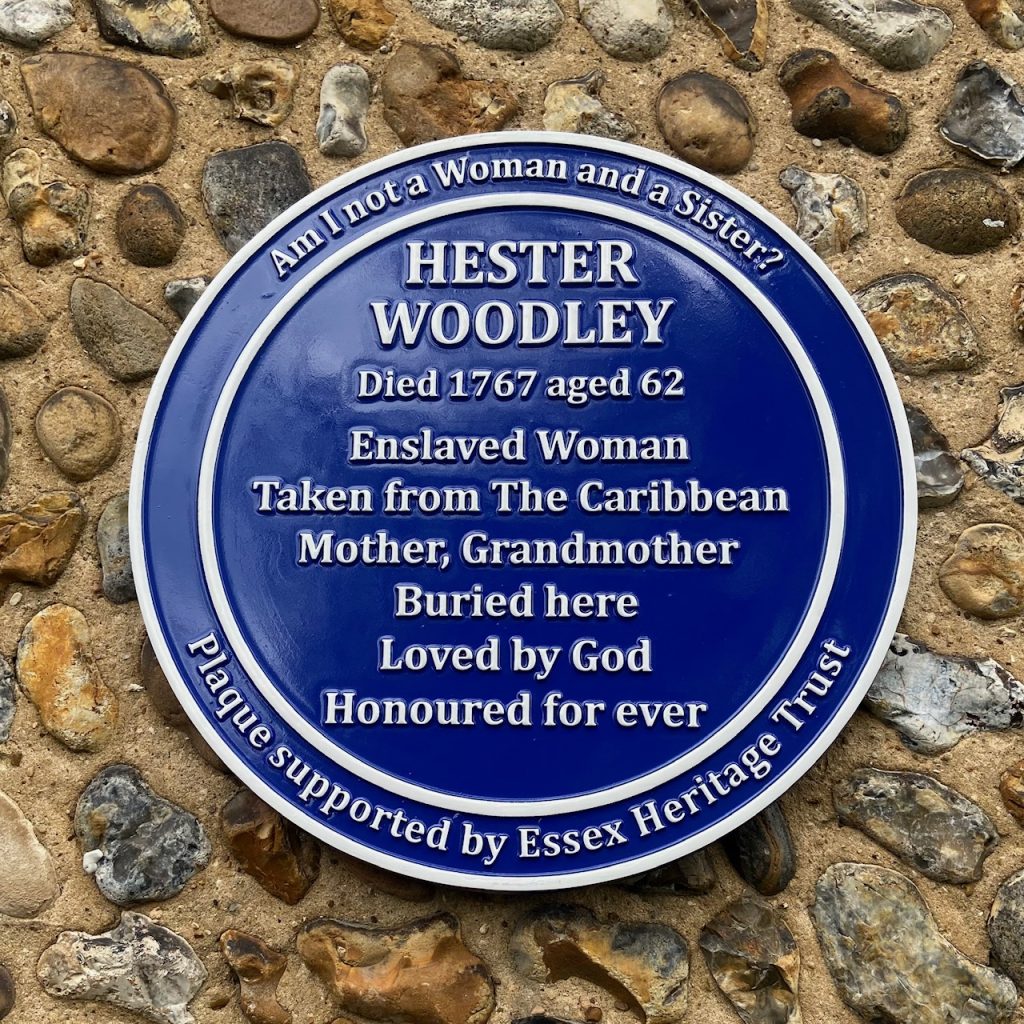

Following a period of research supported by Arts Council England and Southend-on-Sea Borough Council, James embarked on a project called ‘Forgotten Black Essex’ in 2018, where she explored personal and social histories swept under the rug of a white-written English past. She uncovered publicly for the first time a social treasure trove of archival documentation, including parish records, wills and newspapers reports. James focused on unearthing stories from the lives of two women of colour in particular. The first reflection concerns the story of Hester Woodley who arrived in Harlow from St Kitts during the 1700s as a house slave to the Woodley family. When Hester died in 1767, the Woodleys erected a ‘fine headstone’ in her memory – an extraordinary gesture and extremely unusual for a slave. The second story is that of Princess Dinubolu, who came from Senegal to Southend in 1908 to enter a beauty pageant competition – her story provoked a national frenzy.

James’ approach to retelling these stories is really magical; bringing them back to life through a contemporary lens which includes spoken word, still and moving images. James gracefully reinterprets how the two stories resonate with black women living in Essex today. After three years of planning with the Essex Women’s Commemoration Project (EWCP), both women from ‘Forgotten Black Essex’ became the first women of colour to receive blue plaques in Essex this March. EWCP aims to identify past women in Essex whose contributions have been overlooked and for whom there is no commemorative memorial, celebration or other recognition.

I caught up with my mum for her chat in her studio in Southend ahead of the unveiling of the plaques, to talk about her fascination with black British history, and how the pasts of these two women connect to our present.

Storm Thompson: What motivated you to start unearthing the history of black women in the county of Essex?

Elsa James: I can take you right back to doing the school run for your younger sister in 2017. I was listening to Dr Caroline Bressey talking on a Radio 4 show, about the face of a black man, a sailor, sculpted into the base of Nelson’s Column in Trafalgar Square. They were talking about pre-Windrush “black presence” in the UK, and I just found this absolutely fascinating. We’re taught about slavery, African American history, civil rights, Martin Luther King etc. But black Romans and black Tudors were just extremely fascinating to learn about. I remember historian David Olusoga documented a program called Black and British: A Forgotten History and I was so wowed by all of this. I thought I would like to respond artistically, poetically and conceptually to a story of a black person from the past, pre-Windrush. I was interested in anywhere that was outside the main city centers because that’s where we don’t expect to find stories of black presence.

Were you always proud to claim your Essex identity?

I was the opposite. I was very ashamed to say I was from Essex up until making ‘Forgotten Black Essex’. This was because of the ‘Essex Girl’ stereotype and my memory of Southend in particular being very National Front from the 1980s. There was nothing apart from the schools that you and your sister attended that I could say I was proud to shout about.

However, I felt proud after I made the project honoring these two black women that had passed through the county throughout history. I’d also been part of a collective called the Essex Girls Liberation Front during lockdown. We seeked to change the definitions and perception of the ‘Essex girl’ – the white Essex girl that is. There are dictionary definitions saying that “an Essex girl is sexually promiscuous, devoid of taste and materialistic”. We had t-shirts saying: “This is what an Essex Girl looks like” and I was wearing it proudly in London.

What music is the soundtrack to your thought process?

I played Solange’s album A Seat at the Table over and over again during the making of ‘Forgotten Black Essex’. The way she uses politics, her beautiful voice and the way the music is abstracted really is a soundtrack to a thought process. Also, Miles Davis. His jazz album Bitches Brew is perfect if I need to get into that creative mode.

What story was the most emotionally challenging story to retell during the making of ‘Forgotten Black Essex’?

Both stories resonated with me on the opposite ends of the spectrum. Hester Woodley’s story hurts because the Woodleys did something so extraordinary upon her death by giving her a headstone. This speaks volumes, because sadly if you were an enslaved person you didn’t get a headstone. You were just buried in unmarked graves. They must have respected her to the maximum which means she must have given them so much more love than you can imagine.

What correlations can you draw between the Black Girl Magic movement now and the energy that Princess Dinubolu was giving in Southend back in 1908?

I’ve often referred to Princess Dinubolu as the first Black Girl Magic in Britain because she was dealing with the white male media establishment of Edwardian Britain. She was talking back to them and giving really witty answers when they were reporting about her story. She feels feisty. One news reporter asked her, “What’s your beauty secret?” She turned round and said she buried herself in the sand right up to her neck and that’s what makes her black skin so velvety. I really salute her because she did something 100 years ago that caused a media frenzy. She was a forward thinking black woman right here in Southend, daring to enter a beauty competition.

You made ‘Forgotten Black Essex’ in 2018. Five years on, both women from the work will become the first women of colour to receive blue Plaques in the county. What does this mean to you?

I’m elated. When I was asked to recommend any amazing women in Essex, of course I said these two women, Princess Dinubolu and Hester Woodley. They need plaques. It’s a very proud moment that my work can make history as well.

If Princess Dinubolu and Hester Woodley could see their blue plaques today, what do you think they would say or how do you think they would feel?

Hester Woodley was enslaved so she would be in total shock to be honoured in this way. I also think the same for Princess Dinubolu. She lived in a time when there was a colour bar which is just nuts, to imagine myself now checking if I’m allowed to do something on the basis of my skin colour.

The end results of the two films look so effortless. Can you talk to me about any challenges you faced during the making of the work?

So for Princess Dinubolu, we know from the records that she wore red. I made the skirt because I didn’t have a lot of funding and I knew I wanted to wear something with a train, but also I wanted it to be contemporary. I modeled it off of my wedding skirt because back when I first left school, I studied fashion and I learnt how to make patterns and sew. I also made the dress that Hester Woodley is wearing. It’s a grey linen dress and I followed a pattern but I hadn’t used a sewing machine for a good 20 years! I remember the needle broke halfway through making the skirt. I had to rush to the shops to buy a new one and I didn’t remember how to put the new needle back in the machine. It was stressful at the time but now it’s funny thinking back to it.

Through your work you’ve immersed yourself in the county of Essex quite a lot. From ‘Forgotten Black Essex’ in 2018 to your most recent solo exhibition in ‘Othered in a region that has been historically othered’ in 2022. Do you intend to explore other regions of the UK or the world?

Absolutely. I feel as though I’ve interrogated the county of Essex for the past four years with my work and it’s now a natural time to put Essex as a theme and location in my work to one side. I have a black neon quote that is currently being exhibited at Gagosian Gallery. It reads the words, “I am here because you were there” from David Lammy’s emotional speech in response to the Windrush scandal. In that speech, he talked about how the story of the Windrush Generation doesn’t actually begin in 1948, it goes back to the 17th century. It’s a profound statement for me because it’s the segue to where I want to go next. I’m really interested in looking at a contemporary narrative about Britain’s involvement in the transatlantic slave trade and the British Empire. I want to spend the next year researching and developing new work that responds to this part of history.

This article was amended on 30 March to remove mention of English Heritage in association with the two blue plaques. An earlier version mistakenly referred to the plaques as in association with English Heritage.

The contribution of our members is crucial. Their support enables us to be proudly independent, challenge the whitewashed media landscape and most importantly, platform the work of marginalised communities. To continue this mission, we need to grow gal-dem to 6,000 members – and we can only do this with your support.

As a member you will enjoy exclusive access to our gal-dem Discord channel and Culture Club, live chats with our editors, skill shares, discounts, events, newsletters and more! Support our community and become a member today from as little as £4.99 a month.