There’s a new American drug claiming to treat women with low sex drives, but is it something that needs treating?

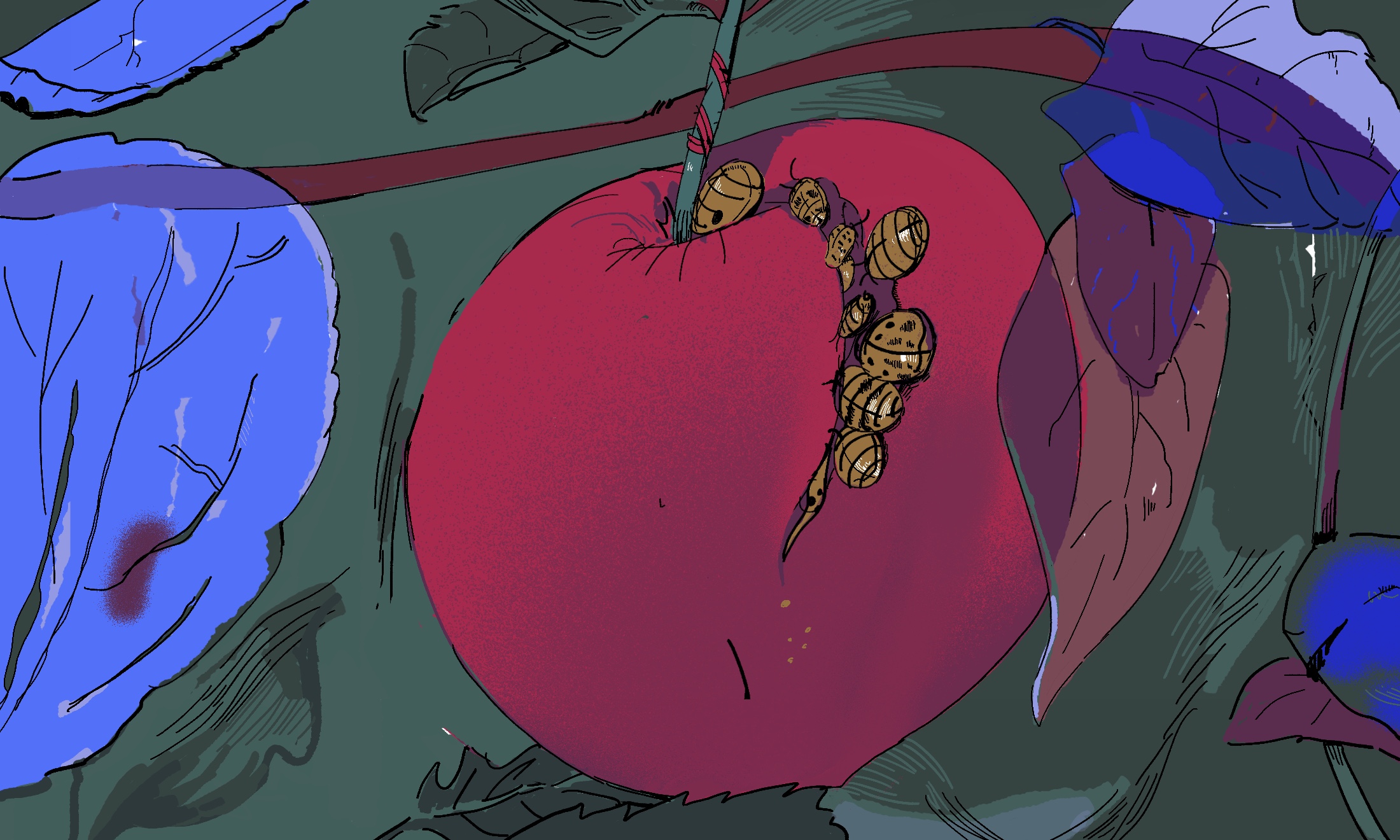

Even in the 21st century, we find people who believe female sexuality is a myth. Post-sexual revolution, females are still grappling with the fight to establish their sexuality being as valid as that of a man’s. Equality in the bedroom is something, one would hope, most people can agree on. So why is there growing animosity toward the first drug approved to treat women with low sex drives?

In 2014, campaign group Even the Score claimed there were 26 drugs approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treating male sexual dysfunction, whilst there were none for treating female sexual dysfunction. Although disputed by the FDA, this claim was weaponised by Even the Score to rally public support for approval of a new drug, Flibanserin, aimed at treating female hypoactive sexual desire disorder.

Flibanserin, initially developed as an antidepressant, increases the brain’s output of hormones dopamine and norepinephrine whilst suppressing serotonin. Dopamine and norepinephrine are two hormones that play a role in reward behaviour and arousal, respectively. The combination of these hormones in action is suggested to help increase female sex drives, but was rejected by the FDA advisory panel twice before 2015. Flibanserin, like most drugs, has a long list of side effects, including dizziness, nausea and low blood pressure – exacerbated by alcohol. The first panel decision, in 2010, unanimously voted against recommending the drug. Panel chairwoman Dr. Julia V. Johnson stated that the drugs’ medical benefit was “not robust enough to justify the risks”.

So if the drug lacked significant medical benefits in 2010, why was it eventually approved?

“There is no real characterisation of ‘normal’ sexual behaviour, so how can something be deemed ‘abnormal'”

Sprout Pharmaceuticals acquired the rights to Flibanserin after the first rejection in 2010. Following the second rejection in 2013, a coalition of 24 women’s groups funded by Sprout, Even the Score, was born to actively campaign for the drugs approval, citing “persistent gender inequality” as the reason for the lack of treatments of female sexual dysfunction. Called out as “a slick pharmaceuticals campaign masquerading as a grassroots feminist movement”, the claims made by Even the Score were fiercely rejected by the FDA, and the opposing campaign New View. Yet the coalition managed to collect over 60,000 signatures on change.org.

In 2013, the FDA recommended Sprout Pharmaceuticals conducted a study into the adverse interactions between Flibanserin and alcohol. In what has been called “a true example of gender bias and sexism in research”, 23 of the 25-people study were men, citing “difficulty” recruiting women who were moderate drinkers. Women and men absorb alcohol differently, so a study predominantly investigating Flibanserin-alcohol interactions in men is clinically irrelevant for evaluating safety in women. Despite this, Flibanserin was recommended to the FDA by votes of 18-6, and subsequently approved.

“Hypoactive sexual desire disorder is an attempt to medicalise sexuality that does not conform to mainstream ideas, much like homosexuality in the last century”

Female sexuality is equally valid as that of males, but the two are not the same. Men and women experience sexual acts, on a physiological level, differently, and there are different classifications for sexual dysfunction in women for a reason. Where women’s physiological response during a sexual act is predominantly triggered by her brain modulating hormone release, in males, increased blood flow can result in an erection. The little billion-dollar blue pill Viagra famously treats males with erectile dysfunction – not low sexual desire. It does so by increasing blood flow to the penis. Flibanserin, although marketed as “female Viagra”, bears no resemblance to the famous drug. And whilst Viagra is taken just before sex, Flibanserin must be taken daily.

The condition that Flibanserin claims to treat, hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD), is a condition defined as an absent or diminished sexual interest or desire that causes distress. Critics, including asexual activists, claim that HSDD is an attempt to medicalise sexuality that does not conform to mainstream ideas, much like homosexuality in the last century. There is no real characterisation of “normal” sexual behaviour, so how can something be deemed “abnormal”?

Leonore Tiefer of the NYU School of Medicine, expressed concerns over the financial success of Viagra being a driving force behind expediting approval of treatments for female sexual dysfunction. In her essay, The Viagra Phenomenon, Tiefer makes a statement that the popularity of Viagra rationalises “the idea of sexual correction and enhancement through pills that it seems inevitable and only fair that such a product be made available for women” – importantly, described as potentially more dangerous than advantageous.

A similar feeling is echoed by Liz Canner’s documentary Orgasm Inc. During her time making erotic movies for drug company Vivus, who were hoping to develop the first FDA approved drug for female sexual dysfunction, Canner changed the direction of her film to focus on the controversy of pharmaceutical companies’ over-medicalising the public. Nine years in the making, Canner’s film, released six years before Flibanserin was approved, is still relevant to today discussion. The film pushes back the veil on an industry who see there is money to be made, whilst exploring the lives of women who believe they have a condition that requires treatment.

Female sexuality is not something to be dismissed, or medicalised for a profit. Whilst there is affirmed recognition of sexual dysfunction in women, as result of surgery or medication, it is important that women should not feel there is something clinically wrong with them for experiencing sex in a different way. Women want and deserve more satisfying sex lives, but only if that is what they choose.