Hogre via Flickr

The gal-dem guide to stopping an immigration raid

How To is a gal-dem series dedicated to demystifying practical steps involved in community activism.

Kimi Chaddah

21 Apr 2022

May, 2021. The image of two Indian men emerging from the back of an immigration detention van parked on Kenmure Street, Glasgow, to rapturous applause captured how a group of people can unite to foil an immigration raid. Representing the importance of community response and building networks, the victory against the hostile environment was a high-profile example of shifting public responses to immigration raids.

Over the years, immigration raids have become part and parcel of the Home Office’s tactics against immigrants living in the UK. Currently, there are 19 official raid squads – known as Immigration Compliance and Enforcement (ICE) teams – which target UK addresses every day.

The Anti-Raids network, a UK-wide network of anti-raids groups, was formed in 2014, while Haringey Anti-Raids, created two years later, is the longest running one in the current network. Other groups are emerging too, with 12 groups starting in the past year. Here, gal-dem explores how to stop an immigration raid with an organiser from the Haringey Anti-Raids network, who has retained anonymity to protect their identity.

“Community activism can play a role in foiling raids and preventing somebody from being detained”

Immigration raids have the potential to happen anywhere, and in the wake of bills such as the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill, which is in its final stages, building resistance is crucial. And bills that openly endorse state enforcement and surveillance are particularly worrying when it comes to the eroded rights of immigrants: details from the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill indicate that any “irregular migrant” in the UK can be issued with a “diversionary” caution for a minor offence, which could potentially result in deportation for a specific “period of time”.

Figures from the Home Office indicate that 24,497 people entered immigration detention in 2021, 65% higher than the previous year when there was a large decline following the Covid-19 outbreak. The number of people entering detention is increasing, but community activism can play a role in foiling raids and preventing somebody from being detained: as part of gal-dem’s How To series, we spoke to an organiser about the active steps we can take to stop an immigration raid.

Where do immigration raids happen and are people notified?

Immigration raids can happen anywhere: the street, places of work, universities, restaurants, public places of worship, and brothels. Factories will often be in industrial, not residential areas. In 2018, a man died after the factory he worked in was targeted. “There’s no expectation that you will know if you’re about to be the target of an immigration raid,” says the organiser. “As a person on the street, whether you’re living in a place or working in a place, there’s no expectation that you will know if you’re about to be targeted.”

Places targeted by immigration raids have shifted over time. “In London, it used to be a lot more common that immigration raids would deliberately happen in public places,” says the organiser, adding that such events would generate a lot of resistance. Heavy policing would typically be present at train, tube and bus stations, such as Stratford station in East London, with officers appearing to deliberately select people of colour for questioning.

“There’s no expectation that you will know if you’re about to be the target of an immigration raid”

But now, rather than raids happening in deliberately public places, such as big supermarkets, the organiser says that smaller independent corner shops have become targets in recent years – shops that have migrant staff, shops where customers are migrants, or shops with items pertaining to a particular culture. Freedom of Information requests conducted by the Anti-Raids network highlight a stark disparity between the number of raids conducted by ‘shops’ as opposed to ‘supermarkets’ within boroughs of London, with the London borough of Croydon experiencing 160 immigration raids in shops from 2016-2020, but only 10 in supermarkets. Details from the Home Office’s Operation Centurion also revealed targets including “Vietnamese nail bars in Manchester”, and in 2016, 97 people were arrested after immigration raids took place at nail salons across the country.

Yet the organiser says that “a large chunk of immigration raids is going to people’s houses,” with residential streets unlikely to have passing footfall in the early morning and therefore, less resistance. “A lot of people may not even notice it’s happening because of the fracturing of communities in the UK in the last few decades,” the organiser adds.

Who carries out immigration raids?

Generally, immigration compliance enforcement teams (who operate within the Home Office) carry out raids, which previously operated within the UK Border Agency. But immigration enforcement may also work with council workers, police officers and other state entities.

“Because there is such widespread resistance to immigration raids, there will often be resistance to immigration enforcement carrying out their duties,” says the organiser. But this often isn’t co-ordinated resistance or organised through a network.

Police and immigration enforcement are increasingly working in collaboration with each other. Operation Nexus, rolled out in 2012, placed immigration officers in police stations. In June 2014, the Home Office launched Operation Centurion, a highly publicised campaign of immigration raids on businesses and homes, while the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill paves way for increased police powers. During a raid, police may stop anybody else from entering the premises, in an effort to pre-emptively block support of people targeted by raids and prevent the public from giving people legal information.

How does community organising play a role in stopping a raid?

At the point of an immigration raid, there are things you can do, and rights that you have, which may support people targeted by immigration raids.

If the police are motivated to arrest somebody, they’ll push a lot of resources in the form of officers towards that goal. But community support plays a key role: while 20 police officers surrounded the van on Kenmure Street in an effort to detain the individuals and prevent others from helping those detained, the immigration raid was unsuccessful.

“It’s not necessarily thinking of resisting immigration raids in the sense of resisting immigration raids as they happen – it’s trying to support communities to build resistance to immigration raids,” says the organiser. That can take many different forms, including running workshops with local migrant centres, so that everybody knows their rights and can support themselves or their friends.

“Getting people to turn up and block raids works only if you know the raid is happening,” says the organiser. In reality, the majority of people don’t know when or where an immigration raid is about to happen, so pro-active resistance is key. Going to places where people are likely to be targeted, and making people aware of their options is now a more common tactic, rather than getting to a place in advance as a result of a tip-off. Resistance now centres on making sure other people know what their rights and capacities are to refuse to comply with immigration enforcement: immigration enforcement don’t always have the right to enter a property without a warrant, and you are not under any obligation to answer their questions.

Is there anything we can do once they’ve been detained?

Once immigration enforcement detains a person, the challenge moves to detention support. “These are issues like making sure you have contact with a good immigration lawyer, trying to stay in contact with somebody beyond the immigration detention system,” says the organiser, “and the fact detention centres are often in the middle of nowhere.”

Groups like SOAS Detainee Support and Bail for Immigration Detainees support people who are detained. Contact numbers for the groups can be found on Haringey Anti-Raids’ flyers, and are useful to give to somebody detained. If an immigration raid has happened and somebody has been detained, going to the place targeted and supporting people via networks is key.

How important is online action?

“Social media can play a big feature in terms of getting people to be aware that immigration raids happen,” says the organiser.

“But they’re predominantly about knowing immigration raids happen in your area; knowing that they have happened, rather than knowing they are currently happening”. By the time someone sees reports on social media, it’s likely that the raid is already over.

Immigration raids can be over in anything from 15 minutes to a few hours depending on the format they take and the number of people being questioned. A longer raid enables people to quickly find out what’s happening and go down.

Hence it’s often a combination of social media that amplifies a case, and existing networks people use to promote information of a raid happening – such as a raid resistance phonetree, eviction resistance network, and getting people present at the time to be involved in support, as in the case of Kenmure Street.

Which interactions can take place with immigration enforcement?

“A lot of what [immigration enforcement] do is speculative,” says the organiser, “and can be resisted by actively not complying in the current rights environment” – whether that’s locking doors or telling them directly to leave. You don’t have to answer questions – Immigration, Compliance and Enforcement teams frequently try to glean information from you which will allow them to take enforcement action against you or somebody else. While there is a chance that if you don’t answer the question, they will arrest you to try and gather further evidence, they have to be quite motivated to do that.

If an immigration officer comes to your house or your place of work, in general, you don’t have to let them in. There are certain situations where they have legal permission to enter – where they have a named warrant, a signed letter by someone in power, or if you’re a licensed premise. While officers can arrest people for obstruction, this requires physically getting in the way.

“Interacting with state officers carries risk – in not answering, but there’s also risk in answering,” says the organiser, “so it’s choosing which feels most relevant to your situation”. People are more likely to be detained if they’re on their own, with no infrastructure to support them.

What is our first port of call if a raid is happening?

Film the immigration officers and/or the police present. Don’t film the person that’s being potentially detained, due to the likelihood of it going viral or being seen by employers. Try and have a friendly chat with them and reassure them about who you are and what you’re doing – carrying the Anti-Raids flyer, found on Anti-Raids’ Twitter, may help inform people of their rights.

“Very often [immigration enforcement] are not doing things based on explicit legal power – often they’re doing an information-gathering raid and operating based on informed consent,” says the organiser, so it’s worth challenging the officers to justify what they’re doing, particularly on camera.

“Leaving immigration enforcement officers when they’re talking to you is emotionally challenging and physically sometimes difficult,” the organiser adds. Try and walk away with the person being detained if you can so they feel supported to leave.

Finally, try to alert people to the raid going on and build support – whether gathering people on the street, trying to get in the shop/the environment, or knocking on doors if it’s a residential area.

If you live in an area without an anti-raids group, Haringey Anti-Raids has made a zine on how to set up an anti-raids group, found here. You may be able to contact whichever nearest anti-raids group to you and other NGOs groups for help and advice starting an anti-raids group.

All the bad bills the Tories are pushing through this year

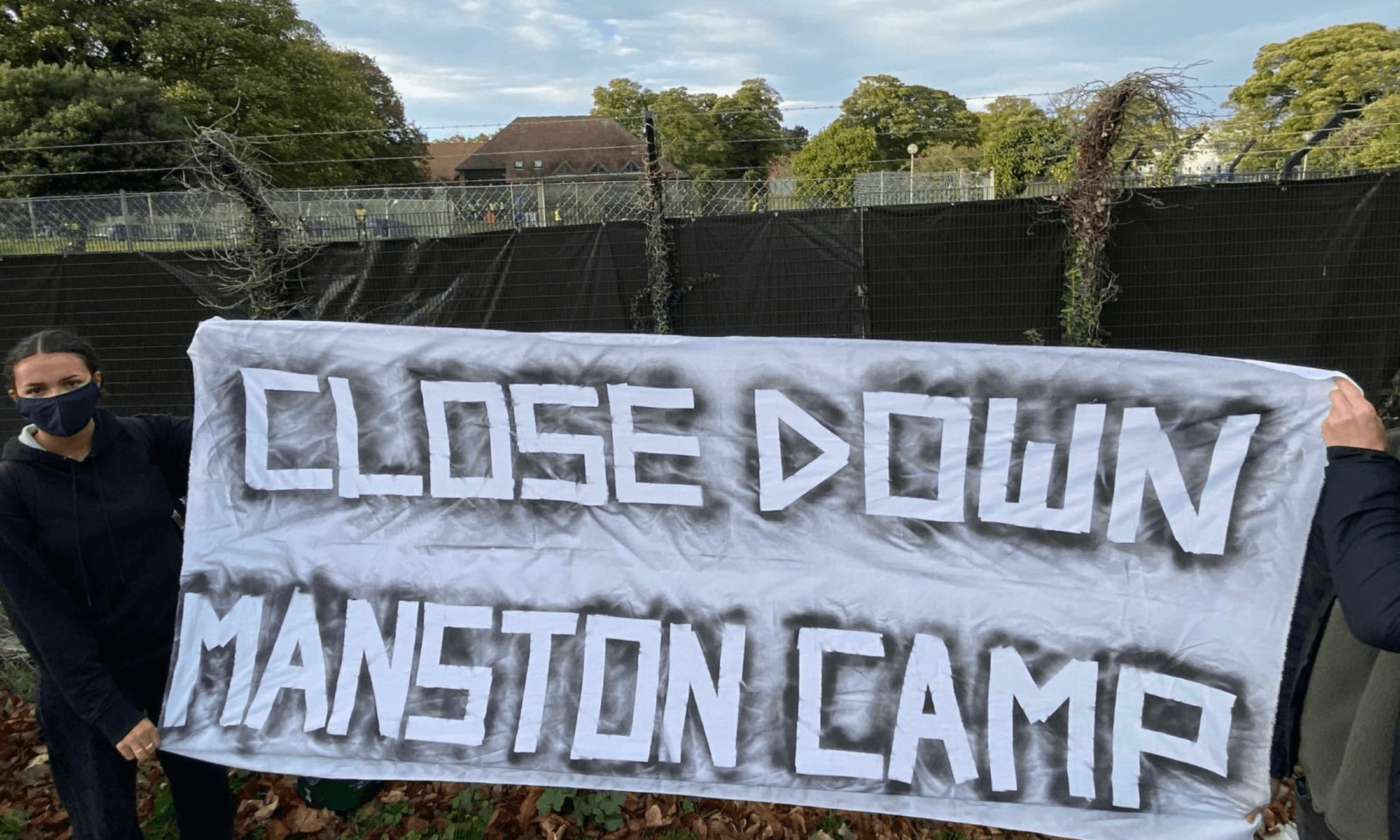

Shut down Manston camp, and take the rest of the UK’s violent immigration system with it

Revealed: ‘Shocking’ number of asylum seeker infant deaths in Home Office housing