‘How does that work?’ – growing up with both Indian and Pakistani heritage

Sana Noor Haq

03 Aug 2019

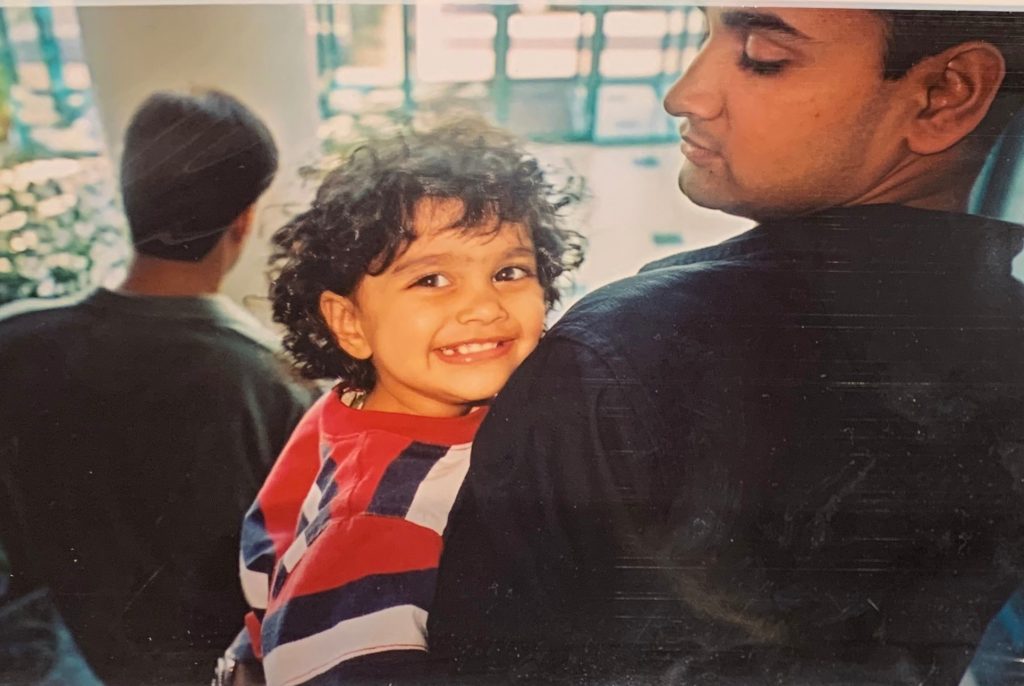

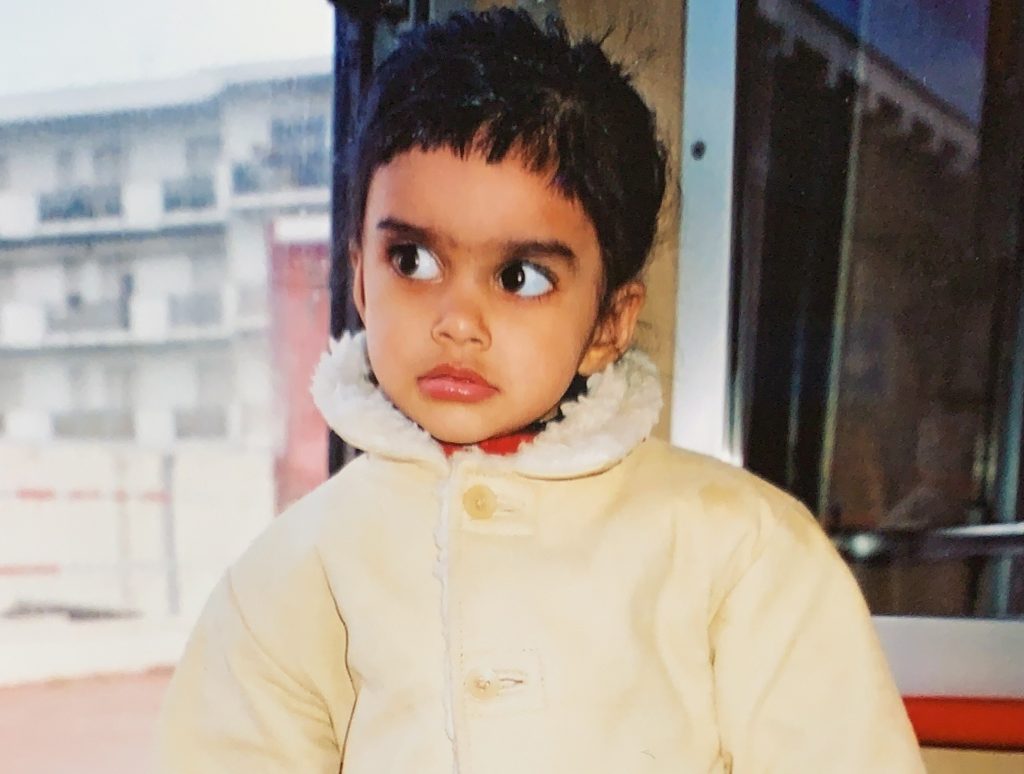

(left to right) My Dada, Nana, Mama, Dadi, me and my Nani

All photography via Sana Haq

TW: This article contains mentions of rape and religious violence.

I have quite a lucid memory when it comes to secondary school. I remember one day sitting in an IT room with a bunch of friends, chatting furiously about hypothetical relationships with our celebrity crushes, never-ending exam stress and our takes on the latest trends in pop culture. However, the conversation segwayed from 2015 headlines to heritage questions. When it was my turn to answer the age-old question, “no, but where are you really from?”, because of course London was not a sufficient response, I spoke with indifference, “well, my Baba’s family is from India and my Mama’s family is Pakistani”. The girl opposite me stared with her eyebrows furrowed, her gaze scrutinising me in disbelief, “How does that work?”

Chewing on the crust of my multi-grain sandwich, I nearly choked. It was the first time I was confronted with the history of my ancestors’ reality, and put to shame for it. For most of my life, the only thing that was problematic about me being Indian and Pakistani was that I always conflated the two, never giving them each the privilege of individuality. Little did I know, there’d be many more interactions like these in the coming years.

“I wasn’t able to recognise cultural prejudice when it was staring me dead in the eye”

I don’t remember what I said to that girl in school, whether I challenged her disbelief or simply drove my thoughts away, navigating the rest of my lunch break as if nothing out-of-the-ordinary had happened. I was stumped by her comment. How was I supposed to react to a question that I simply hadn’t been prepped to answer? Either way, I know now that it was a pivotal point for me; it taught me that I was conditioned to view my personal history through the lens of white educators. I wasn’t able to recognise cultural prejudice when it was staring me dead in the eye.

After school that day, I didn’t discuss the incident with my parents in detail. It wasn’t until a few years later, in August 2017, that I was triggered enough to delve deeper. The 70th anniversary of Partition was a momentous day for Indian and Pakistani people across the globe. The memorialisation of such a colossal historic event sparked a whole range of documentaries, museum exhibitions and photography series sourced from various TV and film outlets that year.

I came to learn that India and England have a knotted colonial history. Britain’s first foray into India was through the East India Company (EIC) in 1757, before the British Empire formally colonised India in 1858. Nearly 100 years later, Britain’s divide and rule strategy meant that growing tensions between Indian Hindus and Indian Muslims bubbled to the surface, as voiced by political parties like Mahatma Gandhi’s Indian National Congress and Muhammad Ali-Jinnah’s All-India Muslim League.

Eventually, on 15 August 1947, British lawyer Sir Cyril Radcliffe was commissioned to draw an arbitrary line down India’s centre and a new country that would operate under Muslim jurisdiction on India’s western side was created: Pakistan. In the nine months that followed, approximately 2 million people were killed in racial and religiously-charged violence and at least 16 million people migrated from India to Pakistan under duress and vice versa.

“When in India, your affiliation to Islam can be questioned, and when in Pakistan, your affiliation to India can be questioned: you can’t always win”

I cannot understate the extent to which the British Empire catalysed animosities between Muslim and Hindu communities in India in order to subsidise their own economic and industrial ambitions. After Partition, India and Pakistan were legally independent of British rule, but socially and politically the legacy of Empire still plagued both countries. British imperialists had plundered natural resources and shaved off India’s wealth and prosperity — the country’s global GDP rate had dropped from 23% in 1600 to 3% in 1947.

There were members of both Gandhi and Jinnah’s parties who firmly believed in a new India and Pakistan; but the violence, mass rape, branded murder and abduction that occurred was devastating, and the emotional and physical trauma of the whole event has been inherited by generations gone by. As a child taught via the national curriculum, Partition was rarely, if ever, taught, and so it makes sense to me why some of my peers may not fully comprehend the imperial horrors of Empire; I certainly don’t. The incident at school made me realise that if I am not privy to my personal history, why should I expect others to be?

It’s true that my Nani and Nana jaan both have relationships with Partition, but with my paternal side of the family hailing from Bangalore in South India, I knew that they had deep-rooted connections that span decades. I interviewed my Dada jaan, asking questions about his journey from India to Pakistan to Liverpool to London. He had left for Pakistan at the age of 15 and then worked in the Muslim League Office, before coming to the UK on the HMS Circassia.

His story, like many others, is truly mesmeric. One thing I notice when talking to Dada about his memories of Partition is that he speaks in a pensive and wistful way, graciously indebting his journey from India to Pakistan and back to Allah (SWT). As an Indian Muslim, treading the line between practising your religion and devoutly claiming loyalties to your country can be precarious. When in India, our affiliation to Islam can be questioned, and when in Pakistan, your affiliation to India can be questioned: you can’t always win.

I will never be able to quite grasp the deep-set trauma that my grandparents have embedded within them, but after asking them about their personal histories, I’ve started to inform my own. During my younger years, my parents never drew out any stark differences between India and Pakistan. Mainly because most of my extended family are practising Muslims, and so the same religion precedes each culture.

I don’t want to erase how the deep-cut wounds and religious violence that existed between Sikh, Muslim and Hindu communities during Partition bleeds into contemporary societies. In his article ‘Community and Violence: Recalling Partition’ Gyanendra Pandey notices how “Partition produced new, congealed and highly exclusive senses of Hindu/Sikh and Muslim communities in India and Pakistan. In the long-term, it also produced new visions of a past that had been exceptionally harmonious, a past in which lives and cultures, joys and sorrows, were shared in ways that partition (and the politics of partition) made impossible.”

Even though both countries have deeply rich tapestries forming unique cultural histories, many of their traditions are still woven from the same thread. There are some subtle distinctions that I’ve noticed between the two. For example Mama likes roti whereas Baba likes rice, or Nani and Nana jaan speak Punjabi, whereas my paternal grandparents speak Urdu (but that has more to do with regional than national differences). However, I’ve felt far more harmony between the two cultures than I have friction.

“Being British-Indian and Pakistani is something I fully embrace, but it doesn’t fully capture who I am”

I’m still figuring out how to direct myself in conversations about identity and heritage, but now I’m better equipped at picking up on subtle remarks here and there from people who are ignorant of the trauma that certain histories carry. I’m realising that I need to think about my heritage with more nuance, respectfully steering my identity outside the steady intent of the white gaze.

Being British-Indian and Pakistani is something I fully embrace, but it doesn’t fully capture who I am. Going back to that incident at school, I felt like there was something wrong with me, eliciting how the fissures between both countries filter through generations and continue to split the identities of young brown children today. I have no claim to other British Asian experiences, but I do urge us to take agency and immerse ourselves in knowledge, constantly reimagining what it means to be a young brown person today.