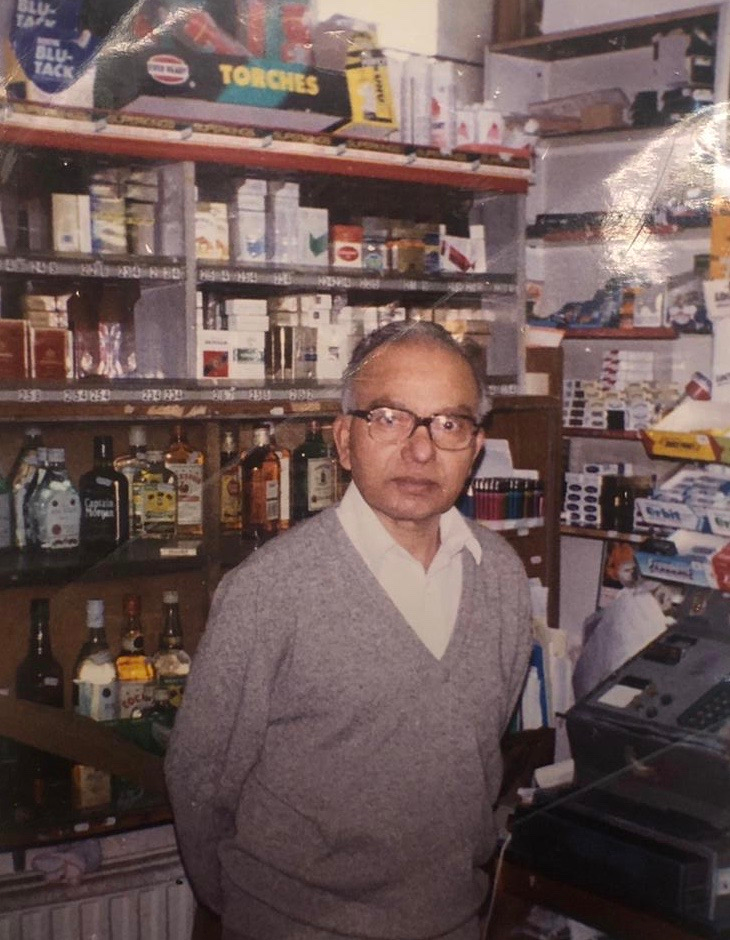

Photography courtesy of Priyesh Patel

How South Asian corner shop culture helped the UK survive Covid-19

As the nation was forced into lockdown, corner shops, the ailing bastion of an era gone-by, were suddenly given a new lease of life. Sana Haq explores their legacy and the lives of the South Asian families who often own them.

Sana Noor Haq

02 Aug 2020

Rows of Twix bars, gummy Haribos and fizzy flying saucers stack the shelves of my local corner shop in Wimbledon. Every Friday after school my brother and I would walk into All Seasons and push open the wide refrigerated crate, ogling at the selection of ice lollies and pastel-coloured Mini Milks. Seventeen years later, despite the passing of multiple indie coffee shops and overpriced clothing boutiques, our local convenience store is still a focal point of the community.

In fact, over the lockdown period corner shops and independent grocers have reported a 63% upsurge in trade. The three months leading to 17 May saw sales made by independently-owned retailers increase by more than two times that of the fastest-growing supermarket chain Co-op, according to the data, insights and consulting company Kantar.

“The lockdown actually had a positive impact on our business,” says 26-year old Sultan Ahmed Sheikh, whose family owns a Londis convenience store in Aberfeldy Village, just north of the Thames. “People who would usually do their weekly shopping in larger stores were now coming to us for their essentials.”

The shop is manned by Sultan, his father Abdul Salam Sheikh, his two younger brothers Sadique and Samad, alongside his trusted childhood friend Wasim Ghaffar.

After saving the funds from a previously-owned video shop, Sultan’s father purchased the store from the local council in 2009. He also bought a flat in Aberfeldy Village. Reflecting on his childhood, Sultan says, “There were eight of us in a three-bedroom flat, but funnily, that was when life felt most grand.”

His grandparents migrated from Bangladesh to the UK in the 1960s during the passing of the Commonwealth Immigrants Act in 1962, which restricted the free movement of people from Commonwealth countries to Britain. Sultan’s father, Abdul, spent his late teens growing up in Tower Hamlets, but Sultan says he wasn’t made to feel as welcome as he expected.

“The immigrant mentality my father had made him hungry to have something solid he could pass down to his children if the acceptance of Asian people in the workplace didn’t improve. He has passed the information he’s learnt to his children. We are now able to run the business while he can take more of a backseat and reap the fruits of his hard labour.”

Growing up atop the corner shop, Sultan has fond memories of serving a range of customers and befriending numerous locals. “The best thing about running a corner shop would be the small daily conversations that form into an in-depth dialogue between two people over the span of a couple years.”

The family’s long-standing relationship with customers has meant that during the lockdown they’ve been in tune with the needs of the community – setting up a delivery service for the elderly and the vulnerable, ordering in items that they wouldn’t usually stock and working with the council to provide food packs for NHS workers who were unable to find time to shop.

However, Sultan recognises the challenges that Covid-19 first imposed on his family. He says that local store owners had to use their initiative and take precautionary measures to protect their customers. For example, at first, his father had to remain absent from the shop after news reports suggested that South Asian people are 2.4 times more likely to test positive for the virus than their white peers.

After easing into the lockdown, Sultan’s family have been able to benefit from customers’ lack of access to supermarket chains. “In terms of relationship with the local community our bond has never been stronger,” says Sultan.

“People who would usually do their weekly shopping in larger stores were now coming to us for their essentials”

“Customers have been showing their gratitude towards us by keeping our doors open during a pandemic. They’ve pointed out how they didn’t realise the importance of local businesses until the lockdown,” he adds.

About 20 miles away is a Londis corner shop in Stoke Newington, owned by 58-year-old Mayank and 55-year-old Anju Patel. Like Sultan, their 26-year-old son Priyesh mentions the coronavirus pandemic as one of the major obstacles that his family has had to juggle. “Every shop owner had dealt with it [lockdown] the way they thought best,” he says.

Due to the government’s shambolic lack of guidance during the pandemic, Priyesh’s family decided to put their own measures in place. These included reducing hours significantly, limiting the number of people in the shop, placing screens in front of customers, offering PPE to members of staff and offering deliveries to vulnerable customers.

“It’s terrible to hear stories like Belly Mujinga’s. Working as a key worker, interacting with the public can be nerve-racking, so for that to happen to her, and for TfL not to keep her safe, was an awful story to hear in the midst of this. In terms of our shop, we kind of had to make rules as we went,” says Priyesh.

“Some customers would come in and comment on other shops, saying they hadn’t taken certain precautions. We thought this input from the public was pretty problematic at times because they had no idea what it was like to be working during a time when everyone was scared to leave their house.”

But for Priyesh’s family, coalescing with the local community wasn’t always easy. “Most of the stories I hear from my parents tell me that when they first moved in the late seventies, there were lots of skinheads in the area thieving, which was hard to deal with.”

Priyesh’s grandparents moved to the UK from Zambia in 1972 due to increased Indophobia in the early seventies, sparked by the former President of Uganda, Idi Amin. They stayed in Leicester for three years, before travelling down to London in 1979. After purchasing the corner shop on Fountayne Road, they each retired and handed down the business, which has now endured three generations.

“When me and my brother grew up on top of the shop, it was still rough in the 90s because there was so much struggle for so many people,” he says. However, streams of gentrification in the mid-2000s meant that his family had to respond to regeneration rapidly. “It changed the concept of our shop quite drastically.”

“My dad has always said that it’s a community shop, and the lockdown has really shown that”

The numbers speak for themselves. Between 2009 and 2017 the average price at which houses were purchased in Stoke Newington grew by 68%, rising to just over £1m, according to the property data network LonRes. Similar research from the digital product designer Amir Dotan has found that over the last 40 years, 21 new restaurants have cropped up in the local area.

Speaking about appealing to customers new and old, Priyesh says, “There are still lots of old customers who are decades old, they still come to the shop. But there are lots of new people from houses which are now a million pounds, which weren’t a million pounds before.”

“It’s difficult because you’re working with two crowds. You’re working with an older crowd, with customers who are loyal to you and you want to support them. But you also want to maintain your business and so you have to respond to the changes in the area,” he adds.

A few months in, Priyesh says that his family has found an equilibrium. “My dad has always said that it’s a community shop, and the lockdown has really shown that. Our customers help us and we help them – we have a really good vibe at the moment.”

“Corner shops have a history that people come for. There’s a smaller chain reaction when you go to a small store, because usually you’re supporting the people working there,” he adds.

Nearly three years ago, 34-year-old Asiyah Javed and her husband Jawad purchased a Day Today Express shop in Falkirk, a large town between Edinburgh and Glasgow. Like Priyesh, Asiyah’s family migrated to the UK in 1972, hailing from Pakistan. Her parents and grandparents moved to Ashton in north England, working 14 to 16-hour shifts in a clothing factory in Manchester. Eight years later they bought their first corner shop in Hamilton, a lowland town south-east of Glasgow. Her family subsequently purchased stores across the country in Glasgow, Coatbridge, Larbert, Falkirk, Grangemouth and Alloa – retiring in the mid-2010s after a decline in physical health.

Asiyah says that running a corner shop day-to-day is strenuous, and amidst the pandemic it’s been “non-stop”. But she makes it clear that she and Javed feel a duty to serve their local customers. “We are like a family with the people in our community, the lockdown has made us closer.”

Asiyah recalls meeting an elderly woman at the beginning of the lockdown who was devastated at the lack of handwash and hand gel available in stores, panicking because it was sold out everywhere. “I couldn’t sleep all night, I decided I needed to act. I went to the shop the next morning and started making hand care packages,” she says.

In the end, they spent about £2000 giving customers over the age of 65 free antibacterial hand gel, cleaning wipes and face masks. “We all need to look out for each other,” she adds. “If you have a corner shop then you have a local community shopping there. You should support them when they need you.”

“Elderly people have more of a chance of catching the virus so they need more help and support. Their families are in lockdown, so we try our best to help all our elderly community.”

“If you have a corner shop then you have a local community shopping there. You should support them when they need you”

Sultan, Priyesh and Asiyah have symbiotic relationships with their local communities, but their accounts of running a corner shop are still prefaced by the institutional racism that runs through Britain’s history. In the 1970s and 1980s, South Asian factory workers in the UK began to lose their jobs after the decline of traditional labour-intensive industries.

The simultaneous expansion of supermarket chains postwar meant that provincial grocery stores were likely to close, unless they were part of groups like Spar or Londis. Members from these conglomerates purchased smaller village stores from wholesalers. More often than not, your local corner shop will be headed by a Londis brand as opposed to being independently-owned.

Racial exclusion and a lack of economic opportunity meant that South Asian workers turned to the establishment of their own small businesses, purchasing corner shops and local restaurants. By 1991, about one quarter of South Asian people in Britain were self-employed.

Prior to that, in the late sixties, the xenophobic Conservative MP Enoch Powell made his “Rivers of Blood” speech, flagrantly comparing mass migration to “watching a nation busily engaged in heaping up its own funeral pyre”.

“We had real problems with Enoch Powell followers. It wasn’t an easy experience. People would say to be careful, ‘Don’t look people in the eye just go quickly and come quickly,’” says 69-year-old Ram Gidoomal, CBE and Chairman of Traidcraft plc, whose family once owned multiple corner shops in West London.

Ram has long been privy to the waves of oppression that strands of South Asian people have endured.

About two weeks before the Partition of India, Ram’s family fled from what would become Pakistan and landed in Kenya, travelling by ship to a port in Mombasa. “Everybody was moving desperately. That was the first migration, losing everything and starting life again.”

In December 1950 Ram was born in Mombasa, his biological father passing away six weeks later. In 1966 Ram’s paternal uncle, who he refers to as his “earthly father”, was handed a deportation notice. Ram was the youngest of four brothers, moving to the UK with 11 family members over a period of a few months. He set foot in London as a refugee on 2 January, 1967. “It was freezing cold and we found ourselves, all 15 of us, looking for accommodation and income.”

As soon as they arrived, a friend advised his family to buy a corner shop. They had moved from a 15-bedroom living space in Kenya to a £150 corner shop on Uxbridge Road in Shepherd’s Bush, christening it G.Bharat.

Within three months of his arrival, Ram’s earthly father passed away. “He put me in charge of the money because I had done my O-Levels. I was there footing all the banking. My other brothers were all good sales people. They would stand in front of the shop and sell cigarettes and chocolates.”

“I had early morning newspaper rounds and then school, then I would go back and run the shop and do homework,” he says. He eventually gained a scholarship to go to Imperial College.

“We provided local therapy. It was fun because we were still one family”

When asked about engaging with the local community, Ram says “We didn’t.” However, he does remember forging bonds with fellow South Asian, Yugoslavian, Nigerian, Ghanaian and Irish migrant communities.

“In that sense, the Irish communities were the people who helped us to make money.” Ram’s family would ask Irish customers what they were missing from their home, and which goods they no longer had access to. He cites publications like the Irish Independent and the Irish Times as newspapers that they imported for Irish customers, as well as Carrolls Number 1 cigarettes.

His family eventually acquired six corner shops, which he describes as “emotional surgeries”. “We provided local therapy. It was fun because we were still one family. We were all together and we were happy – you just had to survive,” he adds.

Since the late 1980s, when Ram’s family sold the first shop, the image of South Asian-owned corner shops has been repurposed in popular culture. Known for their 1990s hit ‘Brimful of Asha’, the British rock band Cornershop reference the socio-cultural influence of corner shops in the UK at the time in their stage name. The band’s frontman Tjinder Singh identifies with his Indian heritage, deliberately foregrounding the stereotype of South Asian corner shops and attributing his politically confrontational lyricism to his dual British Asian identity.

Many British soap operas chalk out a host of South Asian-owned corner shops in various storylines, including Dev Alahan’s store in Coronation Street and the green newsagents First ‘Til Last owned by Ashraf and Sufia Karim in Eastenders in the 1990s. More recently the film director, actor and screenwriter Islah Abdur-Rahman turned his comedy web series Corner Shop Show into a feature-length film in 2019, following the main character Malik as he steps into his father’s shoes of steering the family business.

Over the past 50 years, South Asian-owned corner shops have maintained strong footholds across the UK, allowing locals to “self-organise”, says Dr Noha Nasser, an architect and academic who researches the influence that Muslim communities have on the urban morphology of British cities. “For some minority communities, the corner shop remains an important part of their social fabric,” she adds.

Withstanding waves of socio-political change such as Powellism, Brexit and Covid-19, corner shops continue to act as sites of congregation for Britain’s migrant communities.

As Sultan says, “A local family owned store is a community hub to pass through and bump into old friends – it keeps bridges strong.”