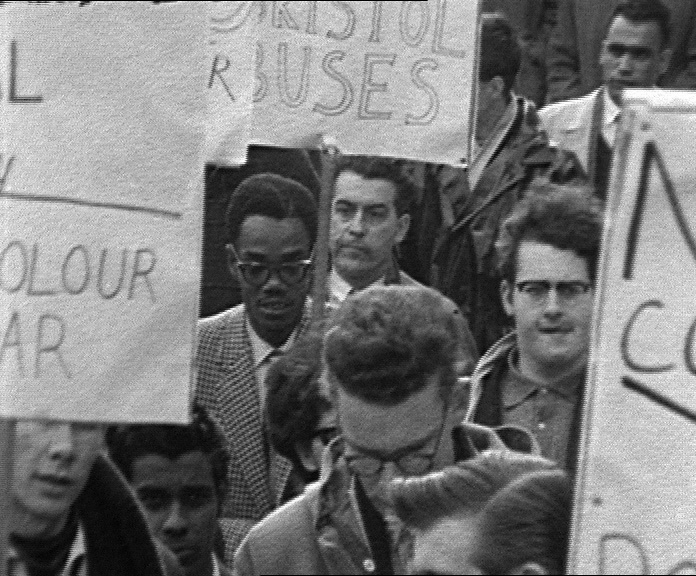

Audley Evans, Paul Stephenson and Owen Henry / Photography by M Dresser, Evening Post via Creative Commons

How the forgotten organisers of the Bristol Bus Boycott changed the course of workers rights

Moya Lothian McLean examines the backlash to the ‘colour bar’, which saw black and Asian people banned from working across Bristol's transport network. Over 60 years later, the battle lines have changed as bus drivers, disproportionately made up of people of colour, are losing their lives to coronavirus. How can we challenge the power structures that continue to diminish the voices of workers?

Moya Lothian McLean

15 May 2020

Rosa Parks. Montgomery, 1955. A name and place etched onto global memory.

Guy Bailey, Bristol, 1963. Forgotten in the annals of civil rights history.

And yet Guy Bailey was at the centre of a protest that would help steer the course of UK history and usher in the 1965 Race Relations act: the Bristol Bus Boycott.

In April 1963, Guy walked into the offices of the state-owned Bristol Omnibus company. He was there for an interview to become a bus driver and was excited; he’d worn his best grey blazer and suit trousers for the occasion. But when Guy presented himself to the receptionist she told him he’d made a mistake. He insisted he hadn’t. So the receptionist informed her manager of his arrival.

“Your two o’clock appointment is here, and he’s black,” he heard her say.

“Tell him the vacancies are full,” the man replied. “We don’t employ black people”.

Guy had run up against what Bristolians called the “colour bar”. It was common knowledge that the council-run bus company refused to employ people of colour. In fact, Guy had been sent to the Bristol Omnibus by a local action group called the West Indian Development, who wanted to challenge their racism but needed to draw it out into the open first.

Once they had, they moved fast. Inspired by the Montgomery bus boycott, the group – led by Paul Stephenson – first mobilised the black community of Bristol, urging a total boycott of the buses. But unlike Montgomery, the black population in Bristol alone wasn’t big enough to inflict enough financial damage to make them change their policy.

“Paul and his co-organisers began a savvy media campaign, inviting local reporters to their protests and encouraging them to draw parallels with civil rights action in the US”

So Paul and his co-organisers began a savvy media campaign, inviting local reporters to their protests and encouraging them to draw parallels with civil rights action in the US.

Meanwhile, Bristol Omnibus doubled down saying that employed “mixed labour” bus crews would bring down the service on the buses. Their comments were condemned by the media, as was the inaction of the Transportation and General Workers’ Union, whose white members were accused of fuelling racist policies through a 1955 vote in favour of not employing black bus crews. They feared that letting black workers join the crew would bring down wages, or push them out altogether.

Bristol University students marching on the TWGU offices

Powerful press messaging encouraged support across the board. The WIDC presented the issue as one of worker solidarity and the right of every person to work – whatever their race. Given cities like London had long set a precedent for mixed race bus crews, the crusade was able to gain the backing of whites, including high-profile Labour politicians like Tony Benn and Harold Wilson. Paul kept up a relentless press briefing, to keep the story alive. Protests were held and Bristol University students even marched on TWGU offices, carrying signs bearing messages like: “EVERY MAN HAS THE RIGHT TO WORK.”

On 28th August 1963, Martin Luther King stood in front of 250,000 people on the steps of Washington’s Lincoln Memorial and spoke about a dream of equality he had.

“The Bristol campaigners had won. But unlike Martin Luther-King, their efforts were not duly noted in British history books”

Over three thousand miles away, Ian Patey, Bristol Omnibus Company’s General Manager, announced the colour bar was “dead”.

The Bristol campaigners had won. But unlike Martin Luther-King, their efforts were not duly noted in British history books, even though their struggle undoubtedly influenced the 1965 Race Relations act brought in by Harold Wilson’s government two years later, which banned “racial discrimination in public places”.

Guy Bailey never joined the bus crews. The experience had left him feeling, “unwanted,” he said. But in 2009 he, Paul Stephenson and fellow organiser Roy Hackett were awarded OBEs. And in 2013, TGWU – now part of Unite Union – issued them an official apology.

Co-commissioned with Free Word as part of their Finding Power in Isolation season.

Britain’s policing was built on racism. Abolition is unavoidable

How Pakistan’s Khwaja Sira and transgender communities are fearing and fighting for their futures

Their anti-rape performance went viral globally. Now what?