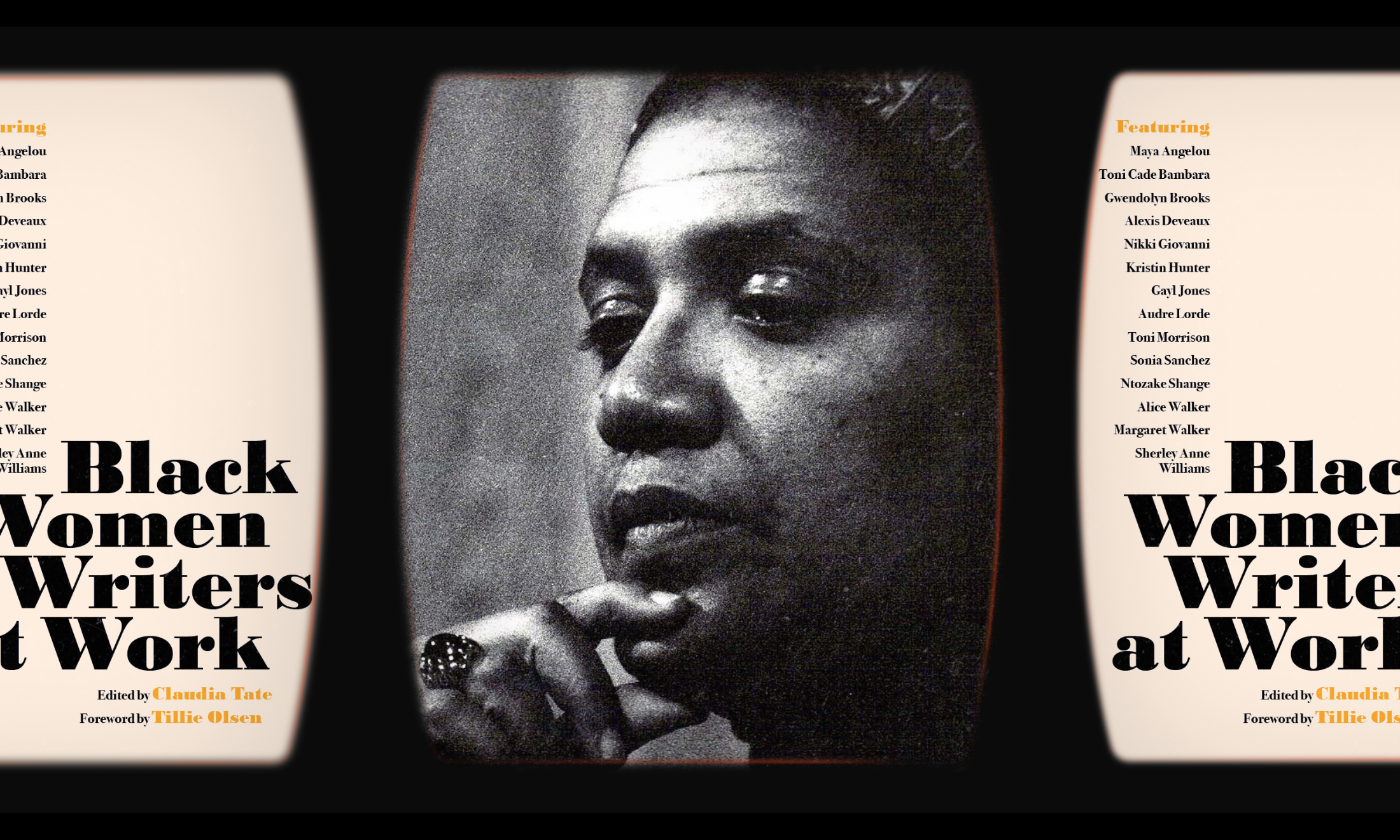

Photography by Texas Isaiah

The author Akwaeke Emezi is a tsunami of artistry. Their talent, creativity and sharp insights create writing that carries readers on a wave of inspiration. They published their debut novel, Freshwater, to international acclaim in 2018 and there is anticipation for their new YA book, Pet, which chronicles the coming-of-age of a thoughtful, sometimes-fearless young girl named Jam who lives in a town where morality is more ambiguous than it seems.

Born in the Nigerian city of Umuahia and raised in neighbouring city Aba, Akwaeke walked into a passion for literature when they were very young. When most other children would spend their days playing, Akwaeke could read and write stories. At the age of five, they made a bargain with the principal and founder of their school, Mrs. Zovannah Onumah, that would become a catalyst for their literary journey.

“She made a deal with me that she’d give me blank jotters, and if I returned them every week with a story inside, I’d get another blank one,” Akwaeke chuckles gleefully over the phone. That incentive gave way to writing poetry, which helped nurture their knack for storytelling. The tale highlights the importance of charging the engines of children’s curiosity. Akwaeke’s flame might not have been ignited if it wasn’t for their teacher’s interest.

Twenty-five years later, at the age of 30, Freshwater became their first published novel. It’s a book that made me feel seen and affirmed. It tells the story of Ada, a Malaysian-Nigerian student and ogbanje [spirit child who dies over and over again].

“I couldn’t get anything published. Everything was rejected, always”

Akwaeke Emezi

In an Instagram post in July, Akwaeke reminded their followers that, like their character Ada, they too were “an ogbanje, thank you very much […] i’m done translating this into flesh terms, b/c then y’all just erase everything else since holding multiple realities is hard.” Freshwater’s autobiographical nature loosely gives an insight into the wholeness of the author – without exactness, but with enough pull to land us on the porch of reality. The attention required to construct fiction that feels so human is staggering.

“Freshwater is written for very specific people, first and foremost,” Akwaeke explains. They say that “though it’s centred in that spirit lens, especially for African people, whether diasporic Africans or continental ones, that’s something we can connect to. We understand how the spirit connects to gender… I’m just writing from a centre that I know.”

Prior to the debut of Freshwater, Akwaeke had a difficult time trying to publish essays in the US. They had moved to Virginia for college, age 16. “I had nothing published in the States – before my book came out,” they say, humorously. “I couldn’t get anything published. Everything was rejected, always.” But Akwaeke, who self-describes as living in liminal spaces, didn’t allow the rejections to deter the plans chalked across their imagination, and as Freshwater was preparing for its international release, the literary universe began to open its doors. Akwaeke was ushered in.

They were nominated for the 2019 Women’s Prize for Fiction, the first time in its history that a non-binary trans person has been up for the award, and they became a finalist for the Center for Fiction’s First Novel Prize. With this context in mind, naturally, there is a buzz around Akwaeke’s forthcoming young- adult novel, Pet.

The quaint Lucille, where protagonist Jam and her parents reside, is a near- utopian town of “angels” who have quelled the “monsters” that used to rule. “It was the angels who took apart the prisons and the police; who held councils prosecuting the former officers who’d shot children and murdered people, sentencing them to restitution and rehabilitation,” the opening chapter explains. Lucille has banned guns, torn down statues of slave- owners and started believing victims when they tell their truth.

In the novel, Jam is tasked with finding a monster who survived the purge, with the help of a supernatural being roused to life from one of her mother’s paintings. In her best friend Redemption’s house, the being “Pet” seeks the monster – who appears to be evil in a way that is quantifiable, despite the fact that Lucille has been so reluctant to admit that such monsters are still living amongst them.

In folklore, we’re always given precise images of monsters, but in some tales, their gruesome appearances contradict their welcoming nature. “It’s all just people with potential to be either,” Akwaeke says about monsters. Jam is exploring what makes a person a monster or an angel and has enough curiosity to reassemble the brokenness of her world.

“A lot of the book is [Toni] Morrison- touched,” says Akwaeke, who even named one of the characters in Pet, Beloved, after Toni’s 1987 novel. “With Lucille, I wanted to create a town like the towns in Morrison’s books where they’re very isolated. The town itself is a whole world. You don’t really hear about people interacting with other towns.”

“I wanted to have a black trans girl, whose name literally means ‘praise me’ and have her be celebrated and loved”

Akwaeke Emezi

Naming their main character Jam, derived from the Igbo term Ja’m (praise me), was also a calculated decision. In a town of wickedness and justness, it is Jam, who is trans, who must be exalted.

“I wanted to have a black trans girl, whose name literally means ‘praise me’, and have her be celebrated and loved. And write a world where that’s not only possible but baseline for a black trans girl,” Akwaeke says. The book’s description of Jam coming out to her parents is written with delicacy and certainty:

She used her hands and body and face for her words but saved her voice for the most important one—screamed out during her first and only temper tantrum, when she was three, when someone had complimented her for the thousandth time by calling her “such a handsome little boy” and Jam had flung herself on the floor under her parents’ shocked gazes, screaming her first word with explosive sureness.

“Girl! Girl! Girl!”

Akwaeke themselves disclosed their gender to the literary world in 2018, via an essay published by The Cut magazine They had realised they were transgender “after falling into a vibrant queer scene in Brooklyn that showed me so many more ways to be than I’d ever known”. But crucially, as an individual living on the margins of certain identities, they find it imperative to let their colours shine most loudly through the words they weave.

“When Freshwater came out, I really debated about writing the essay I wrote for The Cut, because I had been publicly ‘trans’ for a while but not so much in the literary world,” they say, seriously. “I was really terrified about what repercussions that would have for my career. You know, if people would just put me in a little box and be like, ‘Okay, you’re a queer and trans writer – that’s all you write about, that’s all you’re about’.”

Oftentimes, especially in the modern art realm, the practice of platforming the artist above the art tends to cause discord. For a myriad of artists such as Akwaeke, the decision to exist wholly within their content has been intentional. “I know my strong points, and my strong points are my work,” Akwaeke confirms. “I’d rather my work be platformed, rather than me or my flesh identities.”

The foreseeable future holds magic for Akwaeke. The writer is working on the TV adaptation of Freshwater with The Leftovers writer Tamara P. Carter, which is in development at FX, and writing a slew of books – perhaps even a sequel to Pet.

In a world of monsters like the one we live in, Akwaeke has a true gift: the ability to think beyond the binary and present a whole new way of embodying existence. They’re not an angel, but this brilliant writer is truly a deity.

Pet will be published in the UK by Faber & Faber on 7 November 2019. Taken from gal-dem’s print issue on the topic of UN/REST.