I grew up believing it was almost impossible for black people to get skin cancer. Most of my friends and family members thought the same. Both doctors and medical websites will tell you to look out for the usual stuff. Are your moles asymmetrical? Have they grown in size? Are they painful or itchy? What they don’t tell you is that as a black person, you should also be checking your nails, the palms of your hands and the soles of your feet – places that do not get much sun. This is what ultimately led to the death of Bob Marley, who became ill after developing a type of malignant melanoma under his toenail.

While there is some truth to the fact that people with pale skin are at an increased risk of the disease, it is still possible to develop skin cancer as a dark-skinned person. And clearly, we need to be having a conversation about how those in the field of medicine, still don’t fully understand how important it is, nor have the tools, to advise and diagnose people with darker skin correctly.

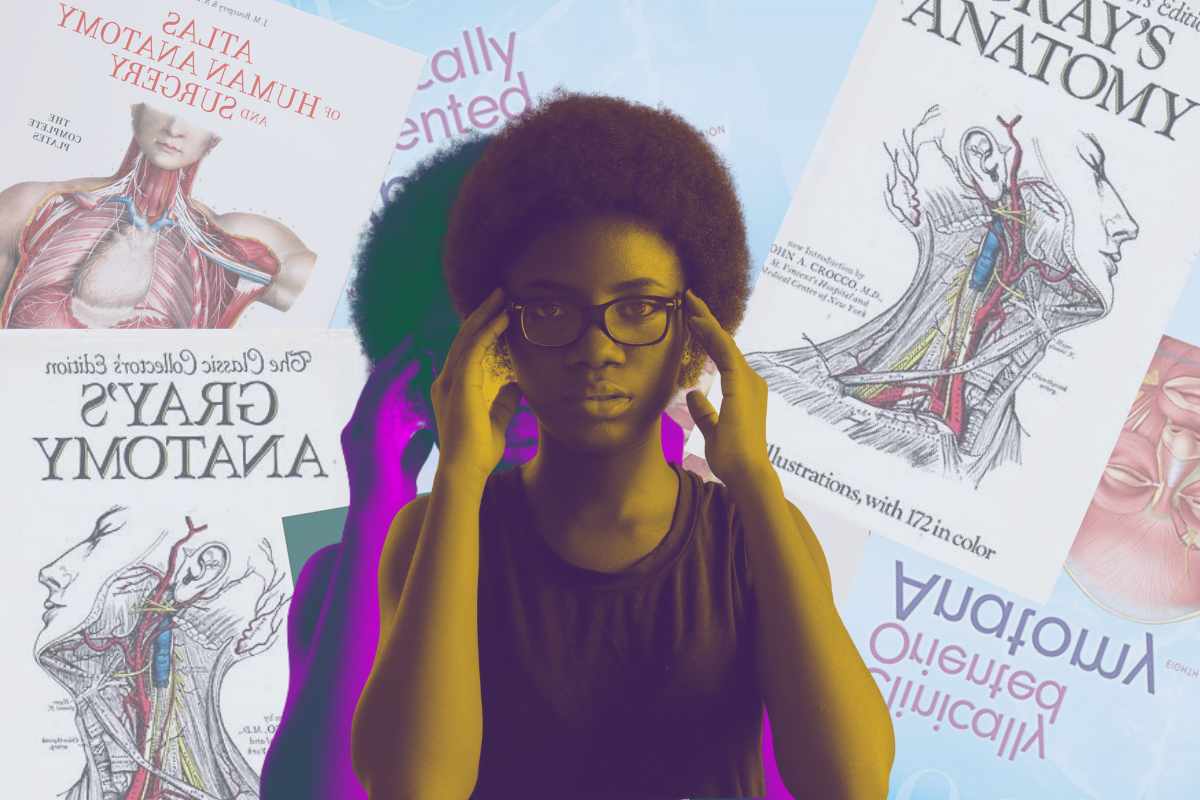

In 2018, Patricia Louie, a sociology Ph.D. candidate, and Rima Wilkes, a sociology professor, co-authored a study published in the Social Science and Medicine journal. Representations of race and skin tone in medical textbook imagery investigated whether the representation of race and skin tone in four popular medical textbooks was proportionate to the diverse US population. They analysed 4,146 images in Atlas of Human Anatomy, Bates’ Guide to Physical Examination & History Taking, Clinically Oriented Anatomy and Gray’s Anatomy. Many images showed just an arm or a leg, making it difficult to identify the race of the person, and leading Patricia and Rima to focus on skin tone instead.

The results were interesting. Race in three out of the four textbooks was proportional to the US population. But, when it came to skin tone, light skin was heavily overrepresented and dark skin was underrepresented. This wasn’t just in the case of skin conditions, but diseases as well, including six common cancers. So what is the impact?

“Eczema, for example, may present as pink or red on someone with light skin. However, it often looks brown, purple or grey on darker skin tones”

The study suggests that this lack of representation may potentially be a contributor to racial inequality in healthcare treatment and could have real consequences for dark-skinned patients. Speaking to me on the phone, co-author Rima says that this lack of representation goes beyond medical school. “A lot of health is just about yourself, right? And your own knowledge, too,” she says. “If people don’t think about themselves when they think about breast cancer they might not be looking for it, and then that could lead to a later date diagnosis.”

Although black people are much less likely to get skin cancer, in the US it’s been found that we are far more likely to be diagnosed at a later stage and more likely to die because of it. This is partly down to a lack of awareness of the risk within the community, but it’s also because healthcare professionals are less likely to suspect skin cancer in people of colour. This can be deadly in the case of melanoma, which spreads very quickly.

According to Rima, a lack of education around dark skin could also send a “normative” message to the kind of patients a doctor may come into contact with, especially if they are using race as a “shortcut” to understanding their illnesses. It was mentioned in the study that cystic fibrosis often goes underdiagnosed in black populations as it can be seen as a “white disease”.

Alongside having less darker-skinned people represented in medical textbooks, there are also very few medical images in health information leaflets or to refer to online. In the UK, even the NHS website lacks information about melanoma in dark-skinned people. As technology advances, there is evidence to suggest that in the case of some skin diseases, a reliance on machine learning could also cause problems for darker-skinned people, because of algorithms based on lighter skin.

A number of other skin conditions vary in appearance based on skin tone. Eczema, for example, may present as pink or red on someone with light skin. However, it often looks brown, purple or grey on darker skin tones. Having an awareness and visual representation of these differences is important so that we all have a better understanding of what is going on with our bodies. Lucky, now there are places like The Black Skin Directory addressing this.

Andrea*, a black British woman, tells me that it took her nearly 10 years to get a diagnosis with Hiradenitis Suppirativa, a painful skin condition that causes abscesses and scarring on the skin. “I was told I needed to practise better hygiene,” she tells me. “I was washing my groin area and underwear with Dettol, washing my sheets and towels with bleach and it still kept returning.”

Symone, who lives with the same condition, also experienced issues getting diagnosed. “I live with this illness every day and suffer but all these doctors want to bring to the table is how I’m ‘overweight’ and ‘how common this illness is for my ethnic group’.” Adding the health issues black women face are not taken seriously. “It’s not fair because we are suffering in silence.”

The research around representation of race and skin tone in medical textbooks was based around North America. So what about medical education in the UK?

In the last few years, I’ve seen a lot more coverage on racial inequality when it comes to healthcare. Research by the University of Manchester dispelled the myth that the sun doesn’t damage black people’s skin. It’s been found that black mothers are five times more likely to die during childbirth than white mothers and black people are four times more likely to be detained under the mental health act than white people. Just as in the US, there are many reasons as to why these racial disparities in healthcare exist, but there is little information on whether similar issues persist at the level of education.

“People need to see themselves across all diseases”

Rima Wilkes

I wasn’t able to find a British version of Patricia and Rima’s study. In fact, there isn’t a huge amount of academic literature about this topic at all. But I did come across an article written about Dermatology of Black Skin, an Atlas published in 1986 by three dermatologists from Haiti, Senegal and France. The book contained a number of images of skin conditions on black people. While this is an excellent attempt at closing the gap in representation, more needs to be done to ensure there is better diversity across all textbooks.

To get a better understanding of what’s going on in the UK. Dr Gabrielle Macaulay, a family GP based in London, believes the underrepresentation of dark skin in textbooks can make it difficult for doctors to improve their dermatology diagnostic skills. “This risk could be minimised if textbook pictures had more ethnic diversity but also if diagnostic ability across a range of skin tones was specifically listed as a learning objective in medical school,” she says.

So what can be done to close the gap? An obvious solution would be to simply include more images of dark-skinned people, but it’s deeper than that. According to Rima, it’s important to have representation and inclusion for a wide range of conditions “because people need to see themselves across all diseases”. Not only should this be done in textbooks, but also in patient leaflets and posters in waiting rooms.

Courtney Taylor-Noel, a final year medical student at Cardiff University believes an increase in medical practitioners of different backgrounds will have a positive impact on closing the inequality gaps in healthcare. She highlights great initiatives like the African Caribbean Medical Association and Melanin Medics who offer support and encouragement to young students from African and Afro-Caribbean backgrounds. “In having more black doctors, there’s hopefully more chance in changing things like textbooks so that we see the human body and health conditions displayed in different ethnicities.”

* Some names have been changed