Doreen Andrewz, Paul Kanyamu

For LGBTQI+ refugees, UNHCR’s Kakuma Camp is no refuge

Kenya's Kakuma Refugee Camp has been hailed as a world-leading example of its kind. But for LGBTQI+ individuals, it is "hell". Namupa Shivute investigates.

Namupa Shivute

25 Feb 2020

Photography and video provided by Doreen Andrewz, Paul Kanyamu

Trigger warning: queerphobia, graphic violence

She stands tall, defiant and graceful, in a cobalt blue and black dress with a white flower print. A huge rainbow flag, held by half a dozen LGBTQI+ refugees, frames her. Hanging above the rainbow flag is a smaller blue flag, bearing the letters “UNHCR”, the acronym of camp authority the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. The blue flag is dwarfed by the sheath of rainbow-patterned fabric, and the woman who stands in front of it.

Doreen Andrewz looks like she can take on the world. And in a way, she is. Doreen is one of 70.8 million displaced persons around the world, forced from their homes for reasons including war, exploitation, and – as is the case for Doreen and her fellow activists – gender expression and sexuality. The small protest, fronted by Doreen, is to highlight conditions at one of the world’s biggest refugee camps. Called “Kakuma”, it’s located in the arid desert in northwestern Kenya. With a bandanna partly concealing her face for protection, Doreen addresses “the world out there” about the struggle of queer people in her current home.

“We are all not safe in Kakuma,” she says. “All of us are in fear for our lives”.

Kakuma is no stranger to global headlines – but they’re usually ones of celebration. Multiple media outlets have heaped glowing praise on camp authorities for their encouragement of entrepreneurship and creativity in its inhabitants. In 2018, Kakuma became the first refugee camp to hold a TEDx event where stories of refugees were shared under the motto “Thrive”. The talks highlighted those seeking asylum as people, rather than victims, and pushed the message of being able to overcome adversity through perseverance and self-reliance.

As empowering as the idea seems though, the experiences shared with me from Kakuma camp paint a grimmer picture. As a writer and reporter, I spent time last year in Kenya and Uganda, filming a documentary on the struggle of LGBTQI+ people there and the European roots of African homophobia. During my time in the countries, I crossed paths with powerful activists, whose stories I continued to follow. All roads led to the neglected queer community of the Kakuma refugee camp.

Doreen lives in Kakuma after having escaped her home in Uganda due to increased and state-sponsored violence towards LGBTQI+ people. But despite the Kenyan camp’s population of 192,000 refugees, hailing from over 21 African nations, it wasn’t the haven she had hoped. In recent weeks, Doreen has been struck down weak by malaria. Making contact with her was a struggle. Due to the threat of harassment and violence from cis refugees, as a trans woman, she couldn’t risk waiting in line at one of Kakuma’s three medical centers, which are shared by the entirety of the camp population.

Other times she couldn’t reach out as she couldn’t afford to buy internet credit, for which refugees mostly rely on donations from activists and other friends around the world. Finally, she lost her phone, a major blow. Too often it is her only weapon in an unjust fight where the odds are stacked so enormously against her. She once reached me from an Internet café; another time she had fleeting minutes to make use of someone else’s phone. To Doreen, such frustrating obstacles are a part of her daily struggle.

“Once someone is identified or suspected as LGBTQI+, queerphobic mobs aggressively interrogate the individual’s sexuality. Often, aggressors patrol the area around LGBTQI+ shelters or intimidate the community through ‘holding meetings’ close to their shelters”

“Being in Kakuma as a trans woman is like being on a battlefield,” Doreen explains, matter-of-factly.

She’s a multi-hyphenate who counts being a hairstylist, rapper and poet as just several of the strings on her bow. Doreen tells me that LGBTQI+ people are both vastly outnumbered, as well as being regularly harassed and attacked by Kenyan locals and fellow Kakuma residents. Once someone is identified or suspected as LGBTQI+, queerphobic mobs aggressively interrogate the individual’s sexuality. Often, gangs patrol the area around LGBTQI+ shelters or intimidate the community through “holding meetings” close to their shelters. Of the estimated 150 LGBTQI+ people at Kakuma, less than 10 identify as trans and the worst form of violence is usually reserved for them. Physical assaults with sticks and metal wires, as well as knife and machete attacks, are common. Doreen’s activism puts her at an even higher risk for harassment and violence.

Through social media platforms, she relentlessly raises awareness about Kakuma’s LGBTQI+ community, fights for trans visibility and assists fellow LGBTQI+ people through psycho-social support groups. During her five-year stay in Kenya, she has managed to escape to the capital Nairobi several times, risking arrest and assault on the road. For a more efficient allocation of resources, UNHCR encourages refugees to stay at the camp which means that runaways begging to be accommodated in Nairobi are more likely to be issued with a movement pass to return to the camp.

Nevertheless, Doreen remains defiant and her activism has been constant. Her bravery and sense of principle sometimes border on the incredible. In 2018, she refused a resettlement opportunity to the US, calmly explaining that she would hate to be “smiling in a country that has taken so many of my kind”.

“A few days before Purity’s departure to Sweden, two cis male refugees visited her, demanding money. When she refused, they threw Purity out of a second floor window, leaving her with fractures in both legs and unable to walk”

For others, the choice to resettle was taken out of their hands. Purity Paige is a friend of Doreen’s and a trans activist who lived in Kakuma from April 2016 to November 2016. Her bright energy is contagious and her wide smile infectious. Purity escaped the camp and she regards it as hell for trans people who she says are specifically targeted “to be wiped out”. She recalls the camp’s horrible living conditions, remembering how snakes would sometimes make their way into their shelters.

Witnessing someone getting bitten by a snake in her early days at Kakuma traumatised her, and she often felt that dying in Uganda might be a better choice. But in Narobi, she has experienced more horrors, including surviving poisoning and the theft of a beloved dog. Purity has also been forced to continue battling transphobia, which has threatened her resettlement hopes.

Purity planned to leave Kenya for Sweden on 11 February 2020. But a few days before her scheduled departure, two cis male refugees known to the Nairobi LGBTQI+ refugee community savagely attacked her. Knowing she was about to leave, they visited her, demanding money. When she refused, they threw her out of a second-floor window, leaving her with fractures in both legs and unable to walk. She says cis male refugees repeatedly target her for robberies and threaten her life to silence her for confronting their transphobia.

After medical treatment Purity was capable of limited movement and prepared to get on her long-awaited flight to safety. However, on the day of her departure, she was refused passage, as the medical escort assigned to her case had a personal emergency and was no longer available to travel with her. Her next scheduled flight for the 19 February resulted in further disappointment as she was once again informed on her day of travel that her accommodation in Sweden was not finalised, as they had not catered for accommodating her and a medical escort. She remains terrified as she awaits further settlement, particularly as she is often attacked for speaking out on irregularities about refugees’ resettlement process.

Paul Kanyamu has faced threats to his life in Kakuma

For some LGBTQI+ Kakuma inhabitants, life in the camp is almost as perilous as the situations they initially fled from. Paul Kanyamu is both gay and a trans man. He was nearly beaten to death by his Ugandan family in December 2018, after neighbours alerted his parents to Paul’s sexual relationship with another man. Paul was stripped, battered and urinated on by a crowd, who then attempted to burn him alive. Bargaining for his life while pleading for forgiveness, he managed to escape by scrambling to the bush, one woman advising him to “run away and never come back”.

Paul took refuge with a friend for a few days but was forced to leave Uganda altogether when his name was published in a local paper, along with details of the attack he’d experienced. The media exposure rekindled his parents’ rage and relatives planned to poison him. “By killing me, they would cleanse the gay curse in the family,” Paul explains. But upon finally making the 13-hour journey to Kenya and Kakuma, his hopes for safety were quickly dashed.

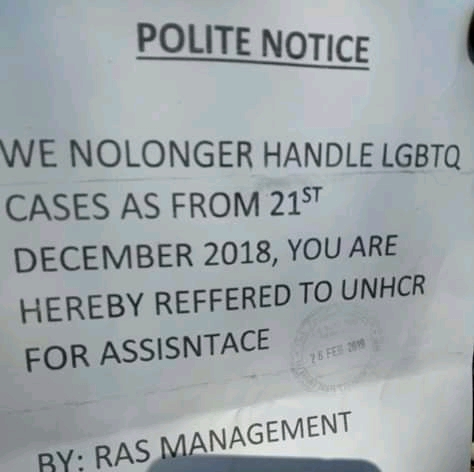

In December 2018, days before his arrival and following the first Pride event held in a refugee camp, LGBTQI+ refugees were evacuated from Kakuma due to increased violence from fellow refugees and residents of Turkana County. Upon arrival in Kakuma, Paul was informed by the Refugee Affairs Secretariat (RAS) that new LGBTQI+ cases were no longer handled by them and that he would have to register in Nairobi. He then had to find his own way to the Kenyan capital. For over half a year, Paul was homeless, spending his nights sleeping by a road. During the day he would beg passersby for food.

A notice posted in Kakuma Refugee Camp by the Refugee Affairs Secretariat

When Paul’s registration was finally completed on 13 August 2019, he was provided transport by UNHCR to his new home: Kakuma. With horror, he realised he was being returned to a camp that had previously been deemed inhospitable for refugees like him. To this day he struggles to understand UNHCR’s decision to return LGBTQI+ people, including 76 of the previous evacuees, into the same violently homophobic environment.

“Kakuma is a nightmare,” Paul declares. Almost immediately, he experienced harassment and threats alongside discrimination from shop owners refusing to sell him essentials, and nurses denying him access to medical care due to his sexuality. In December 2019, when many camp officials were away on holidays, attacks on the LGBTQI+ community intensified again. Paul’s neck was cut during an attack of such brutality that he feared he would die. It was only the intervention of a passing woman that saved him, he believes. Just a few weeks ago, he was jumped again in the showers, by someone shouting homophobic slurs and threatening him with a machete.

Rumours, daily intimidation and their status as a tiny minority means there is an atmosphere of constant fear and justified paranoia among Kakuma’s encircled LGBTQI+ community. “There is a deadly plot to kill all LGBT refugees in Kakuma refugee camp,” Paul posted on his Facebook page recently, the latest in a stream of perceived and real threats to this traumatised grouping. In the upload, Paul detailed how some LGBTQI+ refugees overheard others discussing the “secret” plot, claiming that the LGBTQI+ residents of Kakuma are “teaching” homosexuality to the children in the camp.

Not knowing when to expect the seemingly imminent attack, he says the LGBTQI+ community sleep in shifts to remain on guard. But despite the perpetual danger Paul finds himself experiencing in the camp, returning home is not an option. For Paul, home means certain death. In the meantime, he is awaiting resettlement which he says can take between two to five years.

“The African Human Rights Commission have issued guidelines, advising trans refugees to live in a “more inconspicuous” manner and adhere to cis-heteropatriarchal restrictions of gender, sex, and sexuality”

Kakuma is not supposed to exist in a vacuum though. It’s governed by the UNHCR whose mandate is to protect all refugees. For its part, UNHCR claims to guarantee that the camp is safe but, as residents report, it conveniently ignores the LGBTQI+ community’s need for special protection as a vulnerable group. All three activists I spoke to told me that several meetings and discussions had taken place in recent years, with UNHCR protection officers have resulted in no tangible results, while emails remain mostly unanswered. UNHCR had no response to any accusations raised in this report when asked for comment.

To add insult to injury, human rights organisations such as the African Human Rights Commission have issued guidelines, advising trans refugees to live in a “more inconspicuous” manner and adhere to cis-heteropatriarchal restrictions of gender, sex, and sexuality. The trans community are expected to make themselves invisible and deny their identities; the very restrictions members had hoped to escape from. But Ugandan queers are easily marked and identified by their native languages (Luganda and Rutooro) and their English in a largely Swahili-speaking pool of refuge-seekers.

Even under the LGBTQI+ umbrella, trans people are discriminated against. According to Doreen, fellow queer Ugandans often fear being associated with them saying they attract too much attention “with their lipsticks”. The multinational, ethnically diverse and religiously conservative population of Kakuma, aggravated by a resource-scarce desert environment, is full of anti-LGBTQI+ crusaders.

Paul reports that security officials employed by the UNHCR and the Kenyan government in Kakuma on behalf of camp residents’ safety often reply to the requests for help from the LGBTQI+ community help by saying that they are “tired of homosexuals”. They tell LGBTQI+ refugees that homosexuality is illegal in Kenya and not to expect any protection from them.

“We are refugees because we are not expressing ourselves as society expects us to. Gender identity and self-expression are a priceless gift that God gave us to sail through life”

While the US, Europe, and Western human rights organisations continue to condemn homophobia on the African continent, they simultaneously ignore the desperate calls for acknowledgment and support coming from the African LGBTQI+ community. This is despite it being documented that the roots of legal and cultural homophobia in Africa stretch back to European colonialism. The work of Western aid agencies and western governments remains at best tokenistic and, at worst, violent, with accusations against providers of aid ranging from fraud and assault to sexual abuse of minors.

“We are refugees because we are not expressing ourselves as society expects us to,” Doreen tells me. “Gender identity and self-expression are a priceless gift that God gave us to sail through life… Being visible as a trans person is risky,” she says, but refuses to live life in any other way. Doreen wants to change perspectives by bringing trans lives, in all their forms, “out of the shadows”.

The last time I had contact with her, she let me know that she was helping to get a community-based organisation for LGBTQI+ awareness off the ground in Kakuma. Doreen is continuing to fight for trans visibility and organising for LGBTQI+ people at Kakuma. It’s a mission Purity and Paul are continuing too, from abroad and within Kakuma.

“If we are invisible, we are still dying,” Purity says. “I would rather die at the frontline so that the world knows we are there. We are human enough. We deserve to be visible.”

Britain’s policing was built on racism. Abolition is unavoidable

How Pakistan’s Khwaja Sira and transgender communities are fearing and fighting for their futures

Their anti-rape performance went viral globally. Now what?