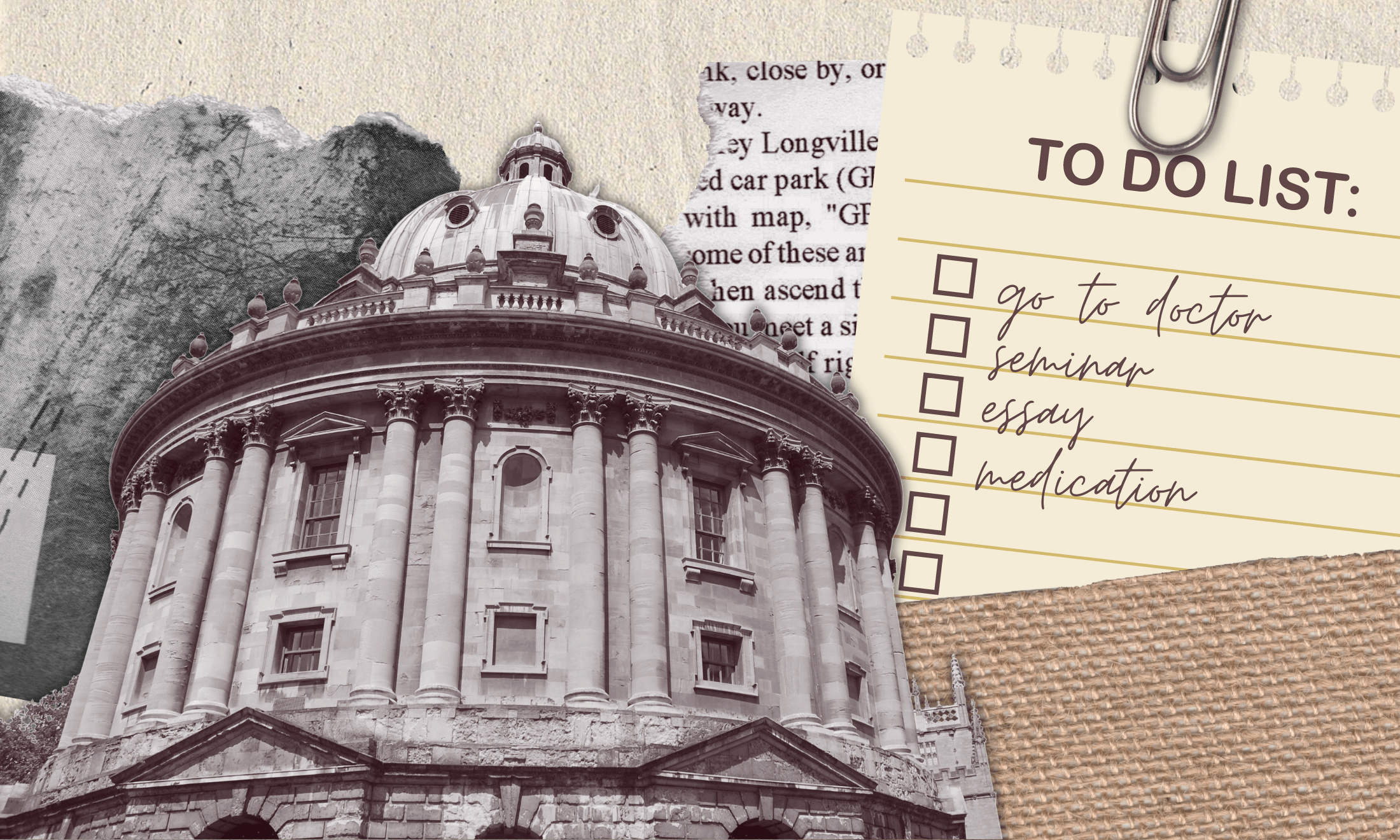

Canva

Finding a student home had always been presented to Amina Mohamed Ali as an easy endeavour, first by friends from home and then by university staff. However, when the 24-year-old law student began looking for her second-year room in London, she discovered that the process was far from simple. Throughout her search, Amina – along with her sister who would be living with her – faced self-professed ‘student-friendly’ letting agents who did not accept the £12,000 maintenance loan she received annually from Student Finance England as evidence that she could afford her monthly rent. Instead, letting agents had a myriad of requirements, including the demand that she provided a homeowner guarantor – a person who agrees to pay the rent if the tenant fails to.

For students from low-income backgrounds, finding a guarantor can be an almost insurmountable challenge. When searching for one, young people are initially advised to turn to parents, with the assumption that they own their home. But in the last 25 years, the housing market has become inaccessible to those on low incomes, creating communities where few residents are homeowners. For many students from low-income households, their parents are not an option.

This is a reality which disproportionately affects UK Black African students, like Somali-born Amina. Only 20% of people in this community own their homes, less than a third of the proportion of white homeowners in the UK. Arab students from low-income households are also at risk, due to the lowest rates of home of ownership in the UK. Black and Arab individuals in general are more likely to be living in rented social housing out of all ethnic groups.

“Suad Mohamed and her housemates were urged to pay a holding deposit of £875 to secure their home, only to realise the property was still being advertised online”

In addition, some letting agents ask that guarantors earn 30 to 40 times the student’s monthly rent. The average amount students pay for rent in the UK is £633 meaning, with this requirement, guarantors need to earn at least £19,000. Considering that in the UK, 13 million households are classed as “low pay”, which means they earn under £19,200 a year, low income students can often find themselves shut out of housing by their lack of financial connections – and forced to shoulder the burden themselves.

This was the case for Amina. Her letting agents gave her the ‘option’ of paying 3 months’ rent upfront, totalling £4,800. Amina had no choice but to scrape together savings from working in order to secure a place, and she considers herself “lucky” for even being able to afford it.

While UK housing rights for tenants are “incredibly weak”, says Jack Yates, communications officer at tenants union ACORN, they do exist. Landlords have to ensure the homes are safe and secure, and carry out repairs when needed. Tenants have protections against illegal evictions. But during the housing search itself, students are essentially on their own.

Undergraduate students – often living away from home for the first time – are also uniquely vulnerable to being ripped off by exploitative landlords and letting agents. Low-income students who’ve lived in social housing may feel more keenly a lack of knowledge about the renting processes, further amplified for those from immigrant backgrounds. Many of these students miss out on learning about the housing system in the UK due to their parents themselves still coming to grips with it.

“Everything I’ve learnt about housing, I taught myself,” says Malak Idris, a student in Manchester whose parents both come from immigrant backgrounds. “Housing isn’t something we talk about. Even my mum who was born here, to immigrant parents, doesn’t talk about housing.”

For those with less familiarity with the rental market, exploitation is rife. Despite a 2019 ban on hidden fees charged by agents, shady business practices still seem to take place. This summer, Suad Mohamed – a second-year International Relations student at King’s College London – and her housemates were urged by their letting agent to pay a holding deposit of £875 to secure their home, only to realise the property was still being advertised online. This fee wasn’t returned to them after a week (which the law dictates should be done) but instead went towards the overall deposit – a sum of money Suad is doubtful she will ever fully get back. “The letting agent made it seem like this was a necessary cost due to the fast pace of the housing market,” she remembers.

“Ainiah Mahmood was unable to find a guarantor and turned to their university’s scheme, only to discover that many letting agents simply do not accept university guarantors”

Universities themselves seem to offer little support to students struggling with finding private housing. When Suad asked her university for advice on finding a guarantor, they suggested she ask her friends.

“Uni student support services don’t really seem to care, they just send you away with a leaflet with little actual support,” Suad recalls. “Knowing that my friends from home in Liverpool are from low-income backgrounds too and not people I can ask just reminds me of how restrictive things are if you’re poor in this country”.

She instead had to approach people from her university for help, placing her in what she describes as “a deeply uncomfortable position,” asking for financial support from her friends’ parents, many of whom she had never met.

While Suad was fortunate enough to find a guarantor through friends, other low-income students have to turn to expensive guarantor companies. These companies are able to fulfill the role of guarantor and step in when there are rent arrears. However, in the case of late rent payment, tenants, rather than owe the landlord money, are left at the mercy of these loan companies.

With guarantor companies quoting upwards of £600 to act as guarantor for a 12-month contract in a big city, this becomes an extra risk and cost that can financially penalise low-income students for circumstances beyond their control.

Although some universities offer in-house guarantor schemes where, for a small fee, the institution can act as a guarantor for the student, in practice these make little difference. Ainiah Mahmood, a neuroscience student at University College London (UCL), was unable to find a guarantor and turned to their university’s scheme, only to discover that many letting agents simply do not accept university guarantors. When they asked for an explanation for why, Ainiah’s letting agents simply said it was out of their hands. Ainiah was left with no choice but to pay £950 a month for a place that did accept the UCL Guarantor Scheme, over £200 more than London’s average student monthly rent of £712. Ainiah’s extortionate rent was a direct consequence of not knowing anyone who could be their guarantor as a low-income student.

The problems do not end once students secure their homes. “We entered [our student] home and it was in a state, it hadn’t been cleaned at all,” Suad explains. “There are multiple dodgy fixings which we’ve called the landlord to try and sort but nothing really gets done”.

“Some students are banding together to win back money lost to unscrupulous landlords”

Suad’s situation only scratches the surface of the problem of inadequate student housing. Many students have had to live in squalid conditions, dealing with mould, infestations and no hot water. And yet, despite all the issues, low-income students like Suad are still expected to pay high rent prices for poor quality accommodation – a poverty premium wealthier students are able to avoid.

Even at the end of a tenancy, landlords are able to capitalise on the vulnerabilities of low-income students. Lucinda, a third year history and politics student at Warwick University, lost out on £450 of her deposit due to the landlord claiming there was damage to the doors and that the house needed extensive cleaning. In reality, says Lucinda, the house was spotless and she and her two housemates were respectful tenants. “I worked all summer in order to be able to afford the deposit only to now have the landlord try and take advantage of me,” she explains. “I needed this money to put towards another deposit but because of the greediness of my landlord, I was left having to work for another summer.”

Often, the only concrete support low-income students can find is through tenant organisations. National tenants union ACORN offers on-the ground advice and action for student renters. ”People often assume that ACORN only operates within the ‘traditional’ private rental sector, but this isn’t the case – we take action for tenants in social and council housing, and for student renters too,” says Jack Yates.

This includes educating tenants on housing rights and using direct action groups to confront landlords. Jack emphasises the importance of teaming up with housemates throughout the housing process as “you will always have more power together than alone”.

Some students are banding together to win back money lost to unscrupulous landlords. In recent years, houses of multiple occupation (HMO) have become a way for landlords to profit off of students in need of accommodation. “These homes are often incredibly cramped and owned by extremely exploitative property developers who have bought up entire streets and therefore are not interested in keeping the houses in good condition, as they view them simply as a way to make lots of money quickly,” says Jack.

“Often, the only concrete support low-income students can find is through tenant organisations”

In Birmingham, students in an illegal HMO reported the home’s unsanitary and unsafe conditions to the council after months of trying to get their landlord to repair problems in the house. Through the tenants’ communal efforts to ensure the rogue landlord was brought to justice, they were able to secure the return of 12 months rent demonstrating how students can successfully fight back.

The reality of low-income student experiences with the private housing sector is a deeply troubling one. The years spent at university are meant to be a time for learning, growth, and enjoyment. Yet, low-income students, especially those from minority groups, may end up being excluded from this experience due to financial circumstances beyond their control. In capitalist Britain, where the ethos is “work hard and you shall succeed”, going to university is presented as the right step to secure financial freedom for a disadvantaged 18-year-old. Yet right now exploited low-income students at university are often still left never feeling truly at home.