Diyora Shadijanova

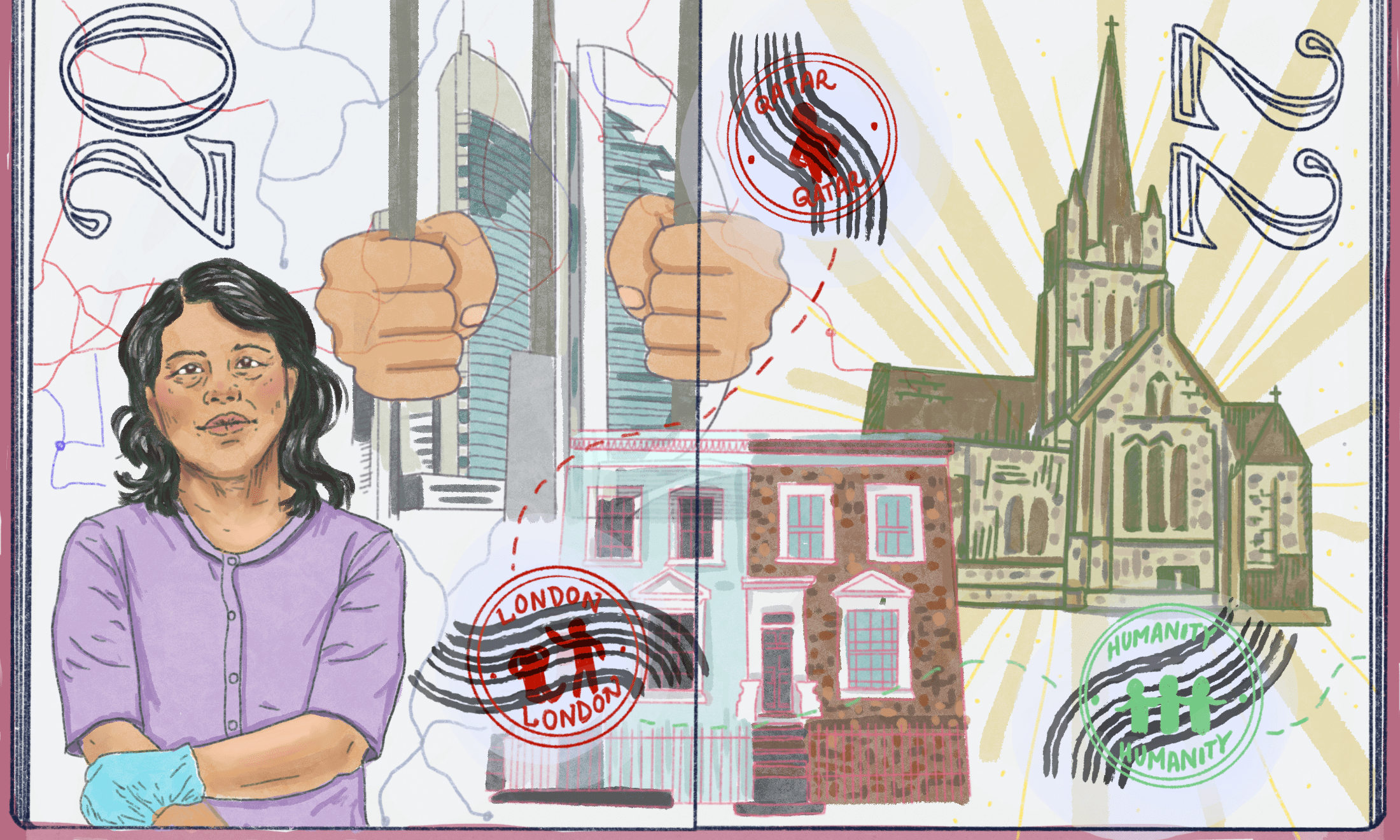

Migrant survivors of abuse face deportation if they go to the police. Could a new law protect them?

The Domestic Abuse Bill could prevent police forces passing the Home Office details used to deport abuse survivors. But is it enough?

Evie Muir

01 Apr 2021

“He would tell me, ‘you’re only here in this country as long as I want you to be here. I can ring the police or the Home Office at any time and they will cancel your visa and deport you’.”

*Hayat is telling me, via Zoom, about the years of abuse she endured from her ex-husband and his family. The 24 year-old was married for four years during which she was physically, sexually, financially, and emotionally abused. Like the 92% of women with insecure migrant status who received threats of deportation from their abusers, Hayat’s immigration status underpinned her suffering and stopped her from reaching out for help.

“[My husband] told me he owned my rights, and that if I were to ever report him to the police, they would take me to a detention centre, and I’d be sent back home,” she remembers. “I was so afraid of that and was scared that my family in Pakistan would be shamed, so I didn’t report him”.

Domestic abuse victims with an insecure immigration status are in double jeopardy. Not only do they face the immediate abuse within their household; abusers then routinely use the police’s alignment with the Home Office as a tool of control. Victims know these threats aren’t mythical either. They are the lived realities of survivors rooted in policy and practice; in the UK where police currently have a duty to pass domestic abuse survivor’s data to the Home Office if their immigration status is insecure.

A 2018 Freedom of Information request showed that 60% of police officers report the immigration status of crime victims to the Home Office. Migrant survivors going to the police for help can face detention and deportation – a shocking failure of a system they are told will support and protect them. These tales ricochet through communities and deter people from reporting abuse as a result.

Aisha’s* is one of those horror stories. When a neighbour witnessed her being physically attacked by her husband and rang the police for help, instead of offering her the support she needed, the police treated the 31 year-old like a criminal because she was seeking asylum and had No Recourse to Public Funds. “They took me to an immigration detention centre, then I was taken to Dover,” Aisha recalls. “The next thing I knew, I received a letter saying I was going to get deported in less than a week.”

Aisha didn’t realise that, as a domestic abuse victim, she was entitled to a Destitute Domestic Violence Concession (DDVC), which meant her immigration status wouldn’t be tied to her husband’s visa, something the police officers who passed on her information should have been aware of. Although she ultimately managed to avoid deportation and remain in the UK, the trauma of her experience remains. “When I look back, I think, how did the police not know this?” Aisha says. “Or maybe they did and their duty to report overruled my rights… That’s what makes me angry.”

Survivors’ stories like Aisha and Hayat are not uncommon. But they could soon be legally protected. In March, House of Lords members voted in favour of amendments to the Domestic Abuse Bill, which would prevent locl authorities sharing data from domestic abuse victims for immigration purposes, and would also provide leave to remain for migrant abuse survivors for at least six months. This follows recommendations made in a December 2020 report, which advocated for significant changes to be made in the ways police respond to domestic abuse survivors with insecure immigration status.

“Aisha didn’t realise that she was entitled to a Destitute Domestic Violence Concession, which meant her immigration status wouldn’t be tied to her husband’s visa”

The report comes as the result of intense campaigning from “BAMER” (Black, Asian, Minority Ethnic and Refugee) organisations, grassroot initiatives and charities like Southall Black Sisters, Step Up Migrant Women and Imkaan, who have led demands for the experiences of migrant survivors to be addressed in the new Domestic Abuse Bill.

Alongside recognition that data-sharing between police and the Home Office deters migrant victims or witnesses of domestic abuse from going to the police, the report highlighted inconsistencies in practice between forces, and a lack of understanding amongst officers about how to support victims who have an insecure immigration status. Also documented are the individual and societal harms caused by a system that makes victims feel unable to report whilst their abusers feel protected.

Southall Black Sisters, a London organisation who submitted the first ever “super-complaint” about police practice on this issue have been calling for a review of law and policy, advocating for a data firewall between police and immigration to be enforced which will safeguard migrant victims. For these reforms to be implemented, the bill must pass its penultimate stage, where both the House of Lords and the House of Commons propose changes. Once this has been completed, the Bill will receive Royal Assent, meaning it is made an Act of Parliament, and the proposals will then become law.

“Figures in the violence against women sector are sceptical as to whether a change in law would see a parallel rise in trust that would enable migrant survivors to approach the police”

While this could instil hope for a more trusting relationship between survivors, support services and the police, there still looms the issue of No Recourse To Public Funds (NRPF). NRPF prevents individuals subject to “immigration control” (such as being in the process of claiming asylum) from accessing government help, like Universal Credit or social housing. Until these restraints are removed, domestic abuse survivors will continue to be more likely to remain in unsafe relationships due to their inability to access financial aid and safe accommodation including women’s shelters and refuges.

Figures in the violence against women sector are also sceptical as to whether a change in law would see a parallel rise in trust that would enable migrant survivors to approach the police.

“There’s a lot more that needs to be done because institutional racism still remains,” says Zlakha Ahmed, CEO of Apna Haq, a Rotherham-based BAMER domestic abuse organisation. “Until that’s acknowledged as an issue, women from [migrant] backgrounds aren’t going to get the right support. The government, and all domestic abuse organisations, not just BAME ones like us need to commit to awareness raising. There needs to be a huge community presence to rebuild trust”.

Survivors also confirm that there is a mountain to climb. “It will take a lot for me and my people to trust the police again,” adds Aisha. “They’re the enemy – they work for the government and the government doesn’t want us here. How can we trust them?”.

For some VAWG activists, police misconduct demonstrates the need for alternative community-based solutions to aid survivors like Aisha and Hayat. Abolitionists argue that now is a prime opportunity to remove resources from the police, and fund community-focused reparative and restorative solutions instead.

For migrant abuse survivors, the increased attention given to gendered violence in recent weeks is of little comfort, unless accompanied by radical legal reform that will see them protected from detention and possible deportation. Priti Patel is sponsoring new immigration legislation that seeks to make an already hostile environment even more difficult to navigate for refugees by criminalising many seeking asylum in the UK, while her proposed Police Crimes, Sentencing and Commissioning Bill aims to give greater powers to the police. In this context, the situation for migrants with an insecure immigration status looks dire.

Amendments to the Domestic Abuse bill could help provide vital protection for people at their most vulnerable but it’s imperative that the voice of survivors from marginalised communities are not silenced in this narrative. The state must stop enabling domestic abuse through policy. Until this happens, Aisha says, “domestic abuse victims like me will forever have two perpetrators: our partners, and the government”.

*names have been changed to protect anonymity

Britain’s policing was built on racism. Abolition is unavoidable

How Pakistan’s Khwaja Sira and transgender communities are fearing and fighting for their futures

Their anti-rape performance went viral globally. Now what?