Windrush Day: Memories of a Chinese-Jamaican father

This Mother Country extract journeys through one father's history to uncover a story of Chinese indentured labour in the Caribbean, a Windrush voyage to the UK, and his love of gambling.

Hannah Lowe

22 Jun 2020

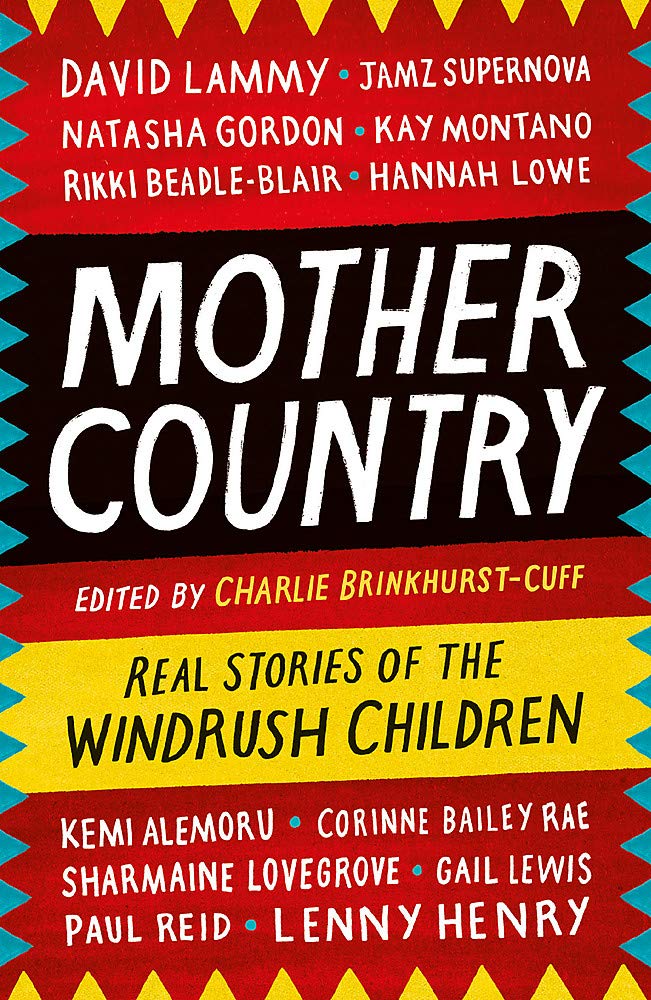

The following is an essay extract from the book, Mother Country: Real Stories of the Windrush, published by Headline.

Hannah Lowe , the author of the essay, is a poet and memoirist. She has published two poetry collections – Chick (2013), which won the Institute of English Michael Murphy Prize, Chan (2016), and a family memoir, Long Time, No See (2015) based on the life of her father. She teaches Creative Writing at Brunel University, and lives with her partner and son in London.

The Ace of Hearts

I only ever caught a glimpse of my father’s dexterity with playing cards on the rare occasion when he would offer me and my cousins a card trick. We’d gather around him in his armchair, a roll-up hanging from his lips, and he’d tell one of us to choose a card, memorise it then slip it back into the pack. Whoever was charged with this task would manoeuvre their card very carefully, hiding it from everyone’s eyes. Once the card was returned to the deck, my father would perform elaborate shuffles, throwing the cards from one hand to the other, fluttering them between his thumbs, inviting one of us to cut the deck, before more shuffling. Then, as casual as could be, he’d run his thumb along the pack, flip it open to the five of spades or jack of diamonds, and say innocently, ‘Is this card yours?’ It always was. We’d be outraged, confused, full of disbelief, begging my father to tell us how he’d done it. But he’d always be tucked behind his newspaper by then, a column of smoke rising above the pages.

Other than these infrequent displays, cards, and, more to the point, what my father did with them, were a half-closeted affair. When he disappeared after dinner ‘to see a man about a dog’ – his favourite phrase – I knew he was going to play cards or dice, sometimes in the East End, sometimes ‘up West’ at the Victoria Casino in Edgware. Occasionally he’d go abroad, packing his holdall and disappearing for days. I have a memory watching him ‘practise’ cards at our home in Ilford, Essex. He’d deal them out beside him on the sofa, scoop them back up, shuffle and deal again, mouthing the numbers and suits to himself. Now I know he was ‘counting cards’ – memorising discarded cards – a practice often used in poker, but banned by most casinos.

Later, my mother – a white English teacher, twenty-three years his junior – told me of my dad’s old saying: ‘If you can’t win it straight, win it crooked.’ She herself discriminated between card counting, which she thought was clever (needing an agile memory and good maths) and my dad’s other methods – loading dice, cutting and marking cards. Did I know he did this? Certainly, I’d seen the paraphernalia in our hall cupboard – a tiny guillotine, a dentist’s drill, pots of ink – but only in adulthood have I fully understood what they were for, or understood that my father was a ‘card-sharp’ or ‘card-mechanic’. And rather than being glamorous or glitzy, like the casinos of James Bond films, this work was unstable and dangerous. He usually returned from his night-trips at dawn, sleeping off the game until lunchtime.

Sometimes, he’d arrive as we were getting ready for school, the smell of tiredness and cigarettes hanging from him. He’d drop his winnings onto the table then climb wearily upstairs to bed. Those piles of notes looked like a fortune but, as my mother has told me since, it was £100 here, £300 there. Enough for bills, a school trip, new tap shoes.

As a child, I wondered who else was sitting around these smoky, basement poker tables, as I imagined them. My only clues were the disembodied voices of men who would phone to ask for Chick, or Chin, or sometimes Chan – his gambling monikers. I’m not sure if they were opponents, organisers, or associates, the same men who sometimes made dice tables in our back garden; the same ones he’d acquire ‘swag’ from, sometimes bringing home a few dresses, some jewellery or a microwave.

Looking back, I see that his lifestyle also enabled him to be a kind of house-husband – home during the day, picking my brother and me up from school in the afternoon, cooking dinner for us all when my mum came home from work. When he wasn’t gambling, or cooking, he was driving – ferrying me to ballet, netball, piano lessons. I spent hours sitting beside him in the car, and it saddens me to remember how little we talked, letting the radio fill the silence. I felt shame about him back then – a complex shame, rooted in the fact of our racial difference. He was black; I looked white. He was also much older than the other kids’ dads, who were milkmen or bank managers or, typically in our area, workers at the Ford car plant. How could I explain my dad’s occupation, which I didn’t even understand myself? In the end, I settled on the ambiguous ‘night-worker’.

“While my classmates went home to fish fingers and chips, the kitchen cupboards in our house held hoisin sauce, jars of black beans, pig’s trotters, sugar cane and plantain.”

As a teenager, my feelings about him, and myself, shifted, slowly and subtly. I’d gone to a multicultural primary school, which I’d loved, but my secondary school was further into Essex, where Essex becomes whiter. There were only a few black pupils, and the curriculum was formal and traditional, where my primary school had celebrated difference. Casual racism was common. Someone found out my dad was black, and for a while, I was called ‘white wog’. A friend’s mother banned her daughter from coming to our house, because my father was ‘foreign.’ In history class, Mr Marsden asked us to write about an interesting member of our family. I wrote what I knew about my father’s upbringing in Jamaica, using a word he himself used – anglocentric – to describe his schooling. When my essay was returned, anglocentric was circled in red, and ‘No Such Word’ written in the margin. I was starting to understand that those in the centre didn’t need the language to describe their privilege.

I wish I had that essay now, to see what I did know back then about my father’s earlier life, because I can’t remember him telling me much. I knew he came from a place called Yallahs on the south-east coast of Jamaica, and was raised by a Chinese father, Lowe Shu-On. His mother was a black Jamaican woman – Hermione. The Caribbean and China were both present in our house through Jamaican sculptures and Chinese crockery, and, in their strongest manifestation, my father’s cooking. He made elaborate Chinese meals – chai sui or roast belly pork – and Jamaican staples – stewed chicken, rice and peas. While my classmates went home to fish fingers and chips, the kitchen cupboards in our house held hoisin sauce, jars of black beans, pig’s trotters, sugar cane and plantain.

When I was sixteen, my father had a heart attack at a card game, an event that marked the start of a decline, physically and mentally. Home from college, I’d find him sitting on the sofa, staring into space. Sometimes I heard him talking to himself in the bathroom, asking over and over, ‘What am I going to do?’ The phone rang less; he was out less often. I had a part-time job by then, and he’d sometimes ask me for a tenner to play in the local kalooki game. He was on blood pressure tablets and still smoking, making roll-ups from dog-ends if he didn’t have the money for tobacco.

I went to university and, away from home for the first time, found myself moving towards my father’s story, choosing modules in postcolonial and black literature, and later enrolling in an MA in Refugee Studies. My father wasn’t technically a refugee, but the course involved the study of the push and pull factors of all types of migration. But I still couldn’t have articulated the link between my feelings about myself and my father, and my academic pursuits. I still hadn’t asked him about his life. And then, without much warning, he died.

At his funeral, the men whose voices I knew from the phone came to pay their respects. One or two I recognised, the rest I’d never seen, including an old man who caught my hand at the wake, and told me emphatically that my father had been the best poker player in London. Perhaps it was a custom in the gambling world, to send themed garlands. They laid them on his coffin – a pair of red dice, the ace of hearts – and over the crematorium tannoy, his favourite Billie Holiday song played: ‘I Can’t Give You Anything But Love’.

The Notebook

When he wasn’t playing poker or cooking or driving me around, my father was in the betting shop. He kept notebooks in which he’d write notes on horses’ form. Those notebooks were always around the house. Imagine my surprise when, years after he died, my mother showed me one that, rather than containing racing odds, held 30 or so pages of my father’s autobiography, detailing his early years growing up in Jamaica – more information about his life than I’d ever heard directly from him. It cemented and expanded on the hazy details I already knew. Here are the opening lines:

I do not know the exact date or year of my father’s arrival in Jamaica but my guess is about 1918 or 1920. From the little information I had of his past life he was born somewhere in Canton in China . . . This vagueness comes about because my father, even though he had parental responsibility for my upbringing, hardly ever spoke to me other than to give a command in relation to the running of the shop which was his livelihood.

The notebook is a testament to all kinds of experience – a life under British colonialism, a rural childhood in Yallahs, an account of Chinese-Jamaican lives. It is also a sad account of parental neglect, detailing the dramatic changes to Lowe Shu-On’s fortune, usually because of losses at Mah-jong, which brought about numerous relocations and shops burnt to the ground for false insurance claims. Various lovers and wives appear, temporary stepmothers to my father; siblings he doesn’t know who arrive without warning and take his father’s favour for a while. Most heartbreaking is the restrained way he records his father’s violence – ‘the most severe beatings imaginable for the most trivial reasons’.

But it is also clear that my father liked to serve customers in his father’s ‘Chiney shop’, as these community grocery stores were called, and which sold everything from rice to beeswax to plimsolls. I remember him talking of the towering shelves he would have to climb to reach the goods, and of the Syrian and Lebanese merchants who came to the shop to sell their wares.

“Finding the notebook prompted me to find out more about [the] Chinese presence in the Caribbean, and to understand this as a legacy of Chinese indentureship.”

Aged seventeen, he left Jamaica, travelling to America as a farm labourer, as did thousands of others, filling the wartime labour shortage. On return, the Caribbean had suffered a serious economic downturn and offered little opportunities. Of this time, he writes:

My thoughts turned to immigration as a way out of my predicament. I had been hearing from people that it was easy to get to England, so I started to make inquiries . . . I soon found out that you could book a passage on ships bringing back servicemen who had fought in the Second World War. So I duly booked my passage on the SS Ormonde paying the princely sum of £28 to get to England.

Many others, returning from war years spent abroad, found themselves in the same ‘predicament’. The war had enabled travel, broadening their sense of the world, and they wanted to travel again. Poverty was a push factor, and Britain, the Mother Country, perpetually lauded as the land of hope and glory, was a logical destination. But rather than being the naïve victims of migration, as this generation is often characterised, unaware of British racism, British rain and the tasteless British food, many had already lived in Britain, or America, where the racism was arguably worse. As David Dabydeen reminds us, ‘Jamaicans have only ever travelled for work’ because money could be made aboard, but rarely at home.* And for my father, there was little in the way of family life to stay for.

My research into his life always has a duality, placing his singular experience against the broader historical context of the times. As a child, I’d wondered if my Chinese grandfather had taken a wrong turn on his way from China to somewhere else, but finding the notebook prompted me to find out more about Chinese presence in the Caribbean, and to understand this as a legacy of Chinese indentureship.

When I travelled to Jamaica in 2013, the Chinese Benevolent Association, a community organisation, gave me a tour of the old Chinatown in Kingston, where Lowe Shu-On had played Mah-jong, and took me to find his grave at the huge, dilapidated Chinese cemetery in Kingston. It was a strange moment, to stand under the burning sun, the cemetery covered in bright pink bindweed. Their expectation, that I would want to pay filial duty, knocked against my knowledge of my grandfather’s abuse, and the ‘long-lasting dislike’ my father held for him, written of in his notebook. The Chinese in Jamaica are a close-knit, family-orientated community, proud of their history, and with strong written and oral memories of previous generations, so it was surprising that no one remembered my grandfather and his Chiney shops in Yallahs. Months after my trip, an email came from the CBA: one very old Chinese woman, now living in Canada, remembered Lowe Shu-On. She had lived close by, and remembered an old shopkeeper she called Uncle, and his son, Ralph (my father’s real name), who went away to England.

Paperwork

The recent Windrush scandal and its coincidental timing with the seventieth anniversary of the Windrush arrival, has reinvigorated an interest in this historical moment and initiated the replaying of the Windrush narrative on multiple platforms. My father’s story is both like and unlike the dominant Windrush story, diverging in several ways, beginning with the fact that he arrived before Windrush. Despite the common citing of Windrush as an originary moment in post-war Caribbean migration, two ships sailed before – the SS Ormonde, the ship he names in his notebook, which arrived in March 1947, closely followed by the SS Almanzora in December of the same year.

I found my father’s name on the passenger list of the Ormonde at the National Archives. He is listed as a ‘clerk’, alongside carpenters, boxers, musicians – 100 or so others making the journey. The recent admission by the Home Office that it has destroyed the landing cards of passengers from this period, makes this and other passenger lists crucially important, as evidence of people’s arrival at a time when the gates were open to Commonwealth migrants, legally, if not in spirit.

His story also diverges because of the nature of his work and his ethnicity. The commemorative practices of Windrush tend to celebrate the lives of those who worked in factories or on the buses or in the NHS – and whose contributions to British life are held up as evidence of their rights to citizenship. But what about those, like my father, whose livelihoods were less orthodox and, for a long time, illegal? Were he alive, would his experiences be seen as less worthy, or his rights to citizenship more questionable? I wonder how he would have fared in the ‘hostile environment’ that has affected so many of the Windrush generation, a policy which demands that British citizens prove their right to live and work here, through presenting paperwork that many do not have available.

When my father died, he left few belongings – his clothes, a razor, an empty cufflink box, a post office account book containing £13, a pack of cards, his notebooks. He had no bank account, no National Insurance card – no official paper trail at all. The ethnic plurality of the Caribbean with its communities of Indians, Chinese, Lebanese, Jewish and Syrian settlers would inevitably have been present in its migrating population too, but rarely do we hear these stories. Maria del Pilar Kaladeen’s work around Windrush considers how the experiences of woman, children and those of mixed or different ancestry like my father have historically been erased from the dominant Windrush narrative, promoting instead a narrative of young Afro-Caribbean men, ‘invading’ Britain – a racism perpetuated at both popular and institutional levels.*

“The recent admission by the Home Office that it has destroyed the landing cards of passengers from this period, makes this and other passenger lists crucially important”

In Britain, the mix of my father’s racial heritage would not have saved him from xenophobia – he still looked ‘other’ – though like many of that generation, traumatised by their experiences, he never spoke of it. But neither was he passive. As a teenager in Jamaica, he had been heavily involved in the anti-colonial independence movement, and in Britain, he joined the Communist Party, sold the Daily Worker outside Hampstead tube, and later, became an active member of the Labour Party. He read newspapers cover to cover every day, and had a deep understanding of politics and systems – indeed of the very system he himself had been oppressed by.

I started writing poetry – my ‘paper work’ – about him, some years after he died. Poetry is the perfect form for not-knowing – it works with mystery and absence, and what is imagined, rather than known – the white space around a poem is the space for possibility. I took the memories I had of his cooking and card- playing to write my first collection and gave it his nickname, Chick. I also wrote about one bigot he was certainly victim of – my nan, my mother’s mother, who never accepted my father and actively articulated her prejudice against him, while living in uneasy proximity; for the first years of my childhood, she resided downstairs and us upstairs, in a house divided in more ways than one. Writing has helped me understand all the facets of identity and to make a claim to my mixedness. I prefer the term without the word ‘race’, since I’m not sure now how useful ‘race’ is, when it cannot adequately describe how people feel about themselves, nor be neatly equated with nationality or ethnicity.

Before, I thought my father’s blackness was like an appendage to my identity. Now I know it is a central part, a part I cherish, and I am glad to be able to put his life – one among many important, migrant lives – on paper.