We Are Lady Parts reminds us to celebrate real Muslim punk stories too

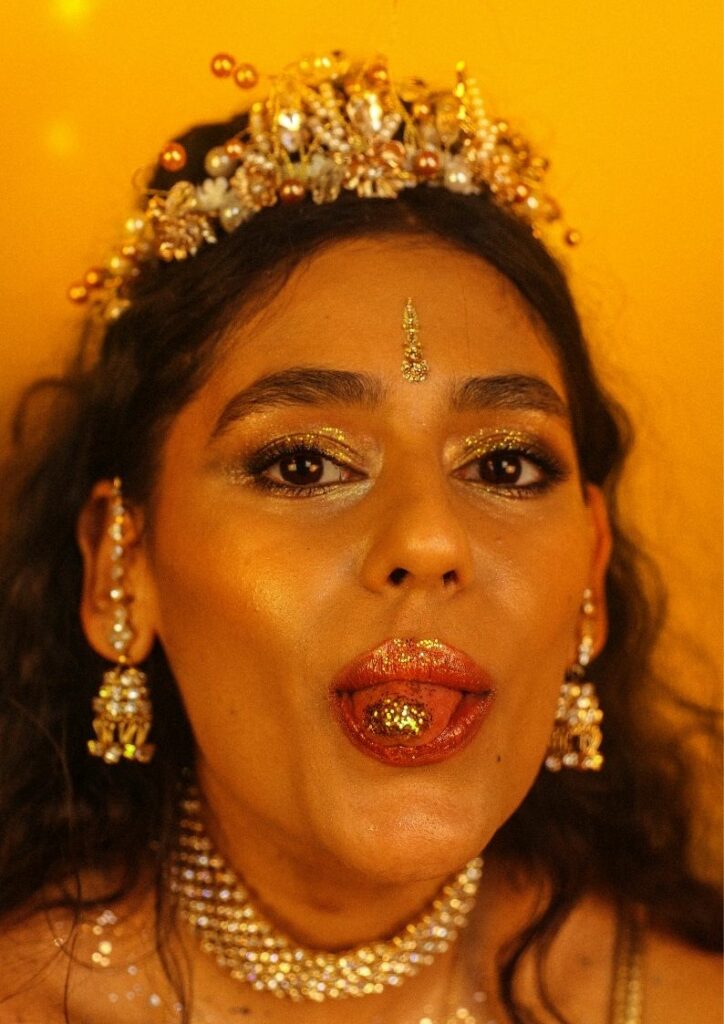

Following the success of a TV show about a Muslim punk band, Nasia Sarwar-Skuse explores the real histories, talking to artists and writers cultivating a scene against the odds.

Nasia Sarwar-Skuse

15 Jul 2021

Top row L-R: Secret Trial Five (Wikimedia Commons), Michael Muhammad Knight (Kim Badawi), Rachid Taha (MorganeC). Central photo: We Are Lady Parts (Peacock). Bottom row R-L: Nadia Javed (Colin Hart), Marjinal (Alexandra Crosby), The Kominas (Atif Ateeq).

Growing up in Manchester, as a brown girl from a Muslim family, I was constantly navigating my multi-faceted identities. I was searching for a language which allowed me to question and express myself. Punk gave me that freedom – a freedom that spills out in the music, with fast-paced songs, hard-hitting political lyrics and the stripped-down sound of the instruments. I fell hard for its energy and anger.

When the all-woman Muslim punk band of Channel 4’s We Are Lady Parts burst onto our television screens, I was excited to see Muslim women depicted in a fresh light. The show has a feel of a romcom, and the influence of real-life Muslim punk musicians is evident in the song title, ‘Ain’t No One Gonna Honour Kill My Sister but Me’ – not dissimilar to the title of a 2011 song by US-based band The Kominas, ‘No One Gonna Honor Kill My Baby (but me)’.

“All too often the music press choses to portray punk as a white European endeavour, overlooking the music made by people of colour and, in turn, many Muslim punks”

Lady Parts allows for new representation, using punk music as a way of exploring a range of Muslim women’s identities. Perhaps this would have been more authentic if the show had featured music from the very Muslim punks that it has drawn its inspiration from.

The genealogy of Muslim punks is rich, but all too often the music press choses to portray punk as a white European endeavour, overlooking the music made by people of colour and, in turn, many Muslim punks. I spoke to three people whose work has been instrumental in building this history, against the odds.

A global scene

Muslim punk dates back to the 1940s when Egyptian American composer Halim El-Dabh pioneered tape music. The likes of French-Algerian artist Rachid Taha were mixing Arabic music with punk – he even joked his earlier recordings may have inspired 1970s London punk band the Clash.

There’s been a vibrant Muslim punk scene in Malaysia since the 1980s, while the core principles of punk and DIY activism can be seen in Indonesia where Marjinal, an anarcho-punk band, started a movement called Jalanan [street] Punk, running communes for homeless children. They taught them how to busk by playing the ukulele as a means of survival on the streets. Their DIY, communal approach to local activism reminds me of a Muslim teaching resonating the Quran 5: 32: “Whosoever saves one, it is as if he has saved mankind.”

In 1979, when the Tories had been voted in here in the UK, three disenfranchised young British-Pakistani men were reeling from the results of the general elections. In a climate rife with racism and riots, they decided to form a band, calling themselves Alien Kulture, named after prime minister Margaret Thatcher’s views on the UK being “swamped by people of a different culture. The band played bangers such as ‘Culture Crossover’ and ‘Asian Youth’.

“Punk’s DIY, communal approach to local activism reminds me of a Muslim teaching resonating the Quran 5: 32: ‘Whosoever saves one, it is as if he has saved mankind'”

Meanwhile in Bradford, north of England, gothic rock band Southern Death Cult were making waves in the early ‘80s. Their British-Pakistani drummer Aki Nawaz began to see a similarity between punk and Islam, such as in the quest for justice. He later went on to form the hip-hop group Fun-Da-Mental, known for its outspoken political views and activism.

On the other side of the pond, bands were forming too: created in 1983, the likes of Fearless Iranians from Hell, fronted by Iranian-American vocalist Amir Memori, performed lyrics mocking the anti-Iranian sentiment in the US.

By the time we entered the new millennium, the third wave of Muslim punk was kicking off.

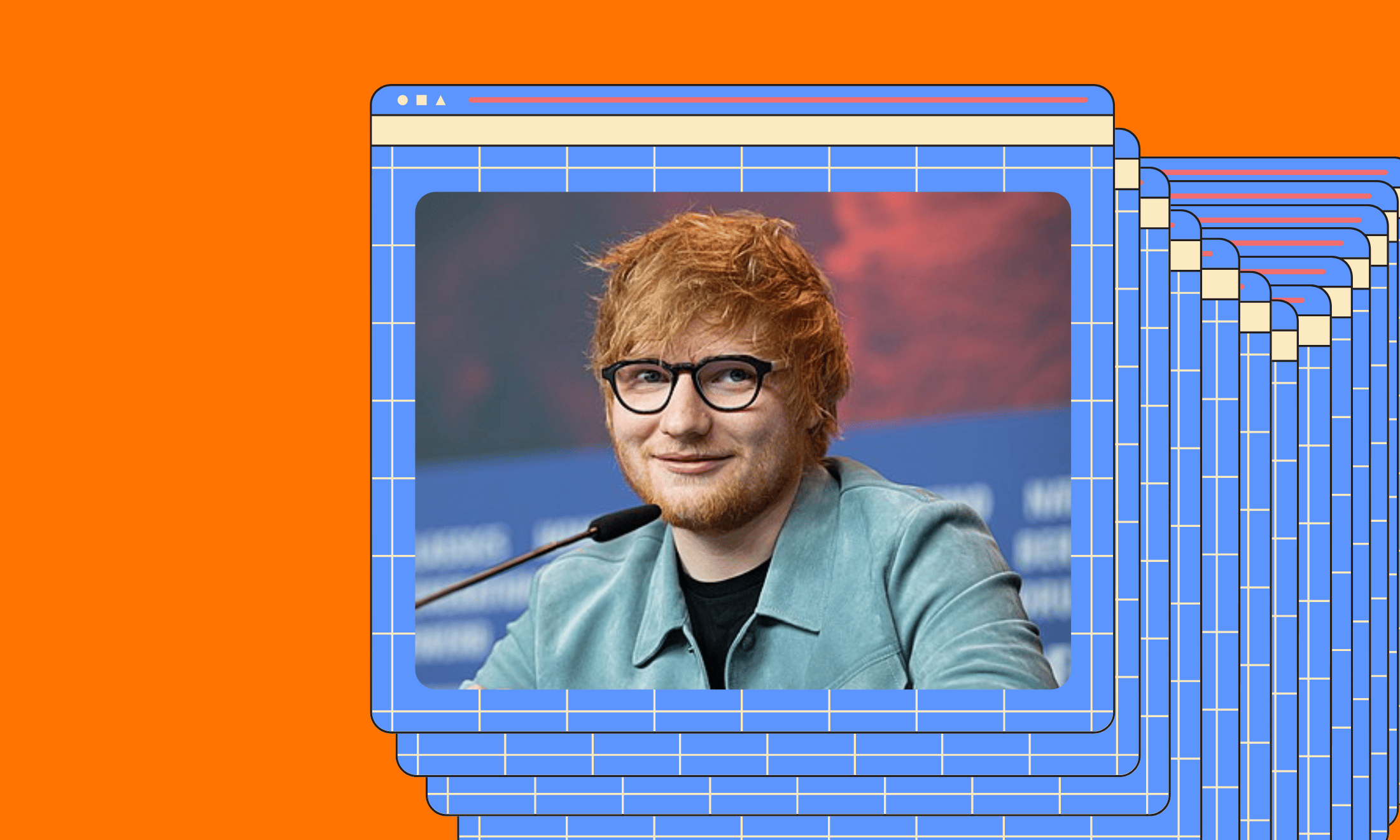

Michael Muhammad Knight

Michael Muhammad Knight’s 2003 cult novel, The Taqwacores, follows an imagined community of Muslim punk characters including straight-edge sufi-drunk punk, Shia, and a burqa-clad punk girl Rabyea (perhaps, in part, an inspiration for Lady Parts’ Momtaz). The book has been described as the Catcher in the Rye for young Muslims, and was adapted into a film in 2010. I spoke with Michael about his relationship with Islam and Punk.

gal-dem: what led you to embrace Islam?

Michael Mohammed Knight: I came to Islam through Malcolm X. Reading about Malcolm’s journey, especially his self-education in prison, I wanted to follow that path of reinventing myself through a pursuit of knowledge. So I started with the books that he named and soon enough, I was holding the Qur’an in my hands.

When did you encounter punk both as music and as a subculture?

It was after I went through a wounding experience in my relationship to Islam. I needed something to tell me that I was ok and that I could stand up and find value in myself even if some transcendent narratives had let me down. Getting into punk culture offered a bit of healing for me when I felt really hurt by religion.

Did you immediately relate to punk?

As a mythology, absolutely. It was always a mythology for me, a new set of narratives for being in the world. Punk was about believing in myself, not apologising for myself and having the freedom to create myself.

“We used to talk about Taqwacore as a middle finger in both directions. It was resistance inside and out”

Michael Muhammad Knight

How did you feel it corresponded with your religion?

Taqwacore was both affirming of my Muslim life and also deeply subversive within it. Islamic history offers lots of precedents for traditions and communities that might exist outside ‘orthodoxy’ or ‘the law’, but as Muslims we often need to recreate those precedents from scratch because we lack exposure to them. My early years as a Muslim were sheltered against everything in Islamic tradition that my mentors deemed heretical, so I missed out on a lot of marginal spaces and margin-celebrating traditions. I didn’t have much awareness of any of that, but taqwacore ended up becoming a space like that for me.

Your book had a far-reaching impact, including Asra Nomani who organised the controversial first women-led prayer with Amina Wadud as imam. Would you say that Taqwacore became a political movement incorporating both Islam and the punk ethos?

We used to talk about Taqwacore as a middle finger in both directions. It was resistance inside and out. It wasn’t going to be about the ‘good Muslim’ kids enforcing a kind of orthodoxy like you see with Christian punk – it wasn’t going to play into Islamophobic or affirm anti-Muslim racism. Taqwacore was its own island, but I liked the politics that people brought to it.

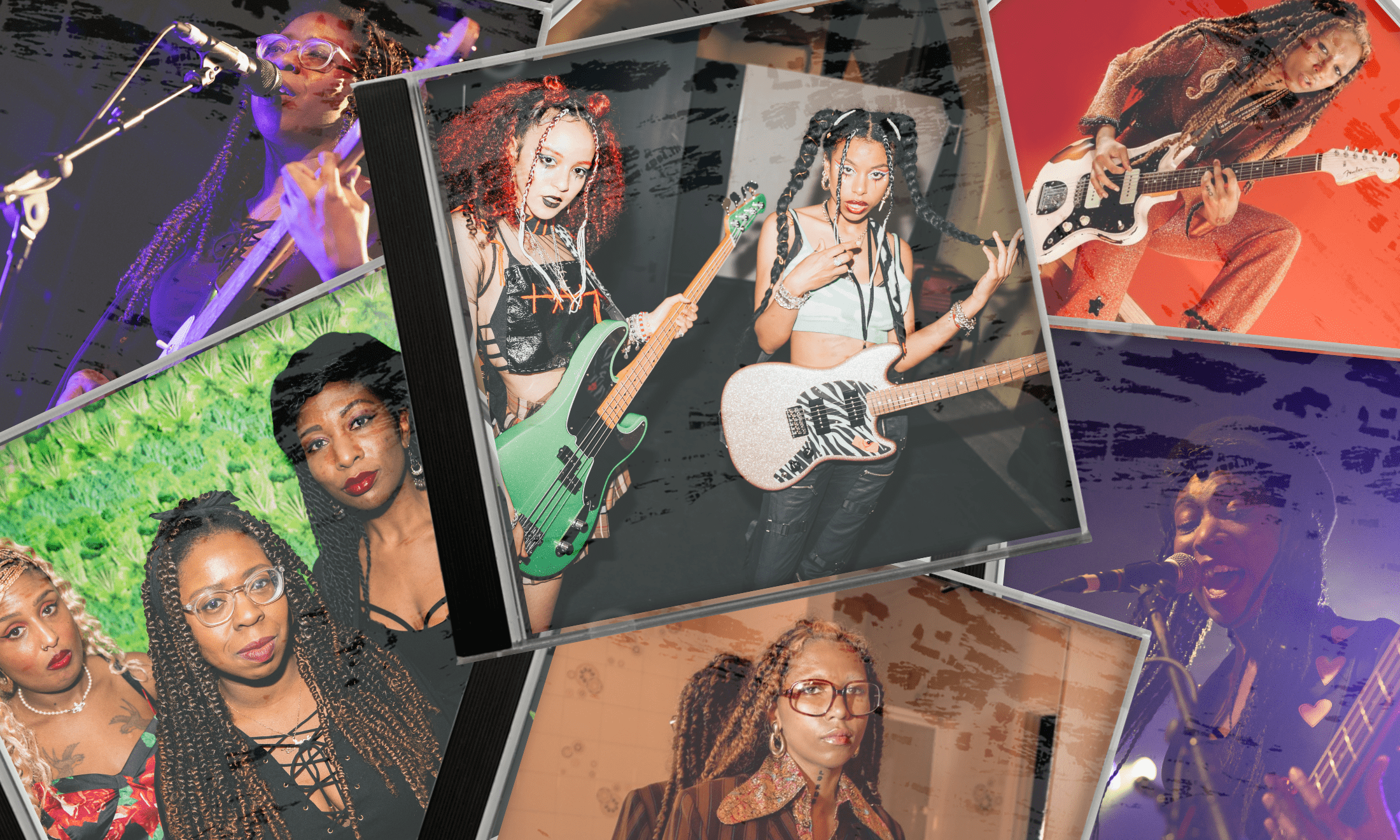

The Kominas

It was during the time when The Taqwacores book was doing its rounds that the raucous US punk band, The Kominas, formed. Soon, The Kominas, along with an all-women Canadian band called Secret Trial Five, plus Al-Thawra and Omar Waqar, found themselves on what was known as the Taqwa Tour (though many of the groups involved would become wary of the label). The Kominas are currently working on their next album, which is set to drop this autumn. I caught up with their bassist, Basim Usmani via Zoom.

“The media blitz was insane, but no record label signed us. ‘There are not enough Muslims to sell to’– [it] became a weird semantic game”

Basim Usmani, The Kominas

gal-dem: How did this meeting of the band and The Taqwacores come about?

Basim Usmani: It was a multi-faceted reality – me and the guitar player had known each other for years. The Taqwacores book came to us like an artifact, but a specific one.

What was the Taqwa Tour like for you as a band?

The Kominas got in a van and played all over the USA. In New York, we met old punks who are the unsung heroes who have had no exposure.

At the time was there a real media frenzy about the band?

The media blitz was insane, but no record label signed us. ‘There are not enough Muslims to sell to’ – [it] became a weird semantic game. Yet, we are not trying to be a reductive Muslim punk binary – The Kominas always had people of different faiths. Being labelled in that way is alienating.

“Often it is capitalism and alienation that leads you to punk. Islam is pre-capitalism and it can be something we can romantically employ to fight capitalism. It’s easier to imagine a Muslim punk than a capitalist punk”

Basim Usmani, The Kominas

What are your thoughts on the intersection of Islam and punk?

There are probably different takes on it. There are some hardcore Marxist and atheist punks in Pakistan and hard line straightedge Muslim punks such as Vegan Reich. In terms of intersection, activism intersects with faith. Often it is capitalism and alienation that leads you to punk. Islam is pre-capitalism and it can be something we can romantically employ to fight capitalism. It’s easier to imagine a Muslim punk than a capitalist punk.

Nadia Javed, The Tuts

Nadia Javed – a London-based Muslim South Asian has been a Muslim punk her whole life. Her trailblazing punk band, The Tuts, challenges oppression from all angles and comprises of three women from three different ethnicities. The Tuts have toured extensively, supporting Kate Nash, Selector and The Specials; currently, Nadia is working on a solo record. I interviewed her to find out what drove a young Muslim girl to pick up a guitar.

gal-dem: How did The Tuts form?

Nadia Javed: High school was a difficult time for me. My parents divorced when I was 11. I was bullied at school, there was just so much racism. I was angry, and I have never been the sort of person who sits back and takes it. I met [The Tuts’ drummer] Bev at school and we decided to start a band. We felt disenfranchised and we had stuff to say. I didn’t have the luxury of guitar lessons, I had to teach myself.

“Punk felt like my armour, a safe space, it felt like home”

Nadia Javed, The Tuts

What drew you to punk music?

I remember going to a gig, [and] my favourite band the Libertines were playing with the likes of Mick Jones from the Clash. The next morning I felt so different, so confident like I was tuned into a new frequency and was totally bulletproof. This feeling made me realise that I didn’t have to be the best, I just needed to get up there and perform. Punk felt like my armour, a safe space, it felt like home, and interestingly it led me back to my femininity.

Would you say punk and Islam are compatible?

For me, yes. Islam at its core is about love and compassion. I try to use my voice and my platform as a means for activism, to help bring about change no matter how small. As a brown woman, people expect you to stay in your lane, or accuse you of seeking publicity – but fighting racism is not a publicity stunt. I will speak out even though in the past this has led to me being sued.

You are involved with a campaign called Solidarity Not Silence, how did that come about?

We are a group of women who are fighting defamation claim made against us by a well-known musician. I am involved because I chose not to be silenced. We recently released a new single called this is sisterhood, and worked with Kathleen Hanna, from Bikini Kill.

“People don’t know I exist because the music industry is less supportive and willing to back artists like myself. At the same time, a TV show on Muslim punks is easier to digest and celebrate – people can accept stuff more so when it’s fiction rather than reality”

Nadia Javed, The Tuts

I’ve got to ask, have you watched the show We Are Lady Parts? If so, could you relate?

Of course I could relate, I was seeing myself on the telly! It’s amazing and also a crazy feeling seeing something so similar to you on the TV blow up after being ignored by the mainstream for so long. The show did make me think about my own identity, the value in being a Muslim punk and the demand for authentic stories. It’s made me proud to be me and [made me think about] how I shouldn’t doubt myself, because my identity and story is valuable. It’s inspired me to want to write a film or TV show about the Tuts. Lady Parts proves how, with good story-telling, financial backing and support, you can get the exposure you deserve. There’s so many people out there who could be fans of my music but don’t know I exist because the music industry is less supportive and willing to back artists like myself. At the same time, a TV show on Muslim punks is easier to digest and celebrate – people can accept stuff more so when it’s fiction rather than reality.

Do you think that you were an inspiration for the show?

Yes, I’d like to think I did inspire part of the show, and Nida [Manzoor, the show’s creator] did tell me the same. Nida and I met back in 2017, after she became aware of me and slid into my DMs on Twitter. We arranged to meet up for a drink and continued to hang out between 2017 to 2019 when the script was being developed, so yeah, I mean, how many South Asian female Muslim punks do you know? She frequently attended our gigs. I actually acted in a short film that Nida shot called Bride or Die, along with Zia Ahmed who was in the writers room for Lady Parts. I’d love to see the show inspire Muslim girls to pick up a guitar and fight for what they believe in.

The most punk thing ever

Perhaps it’s because Islam allows for many diverse ways of believing, with a wide range of ideologies, that it is compatible with the broad punk-spectrum and attracts a vast array of musicians and activists. New people in the scene are emerging, including bands such as The Muslims, a group of queer Black and brown Muslim artists based in the States who formed in 2017 and recently signed to renowned punk label Epitaph Records.

Of course, punk is not some sort of racial equality utopia – this is evident from the way that the music press continues to centre punk as white angst boys with guitars. We Are Lady Parts is an entertaining show, yet it can’t be a replacement for documenting, archiving and celebrating the actual stories of real Muslim punks. These are the people who, despite being overlooked and othered, continue to make their music – and that is the most punk thing ever.