‘No Bears’ looks at how the control over women’s bodies traps us all

Jafar Panah takes us on an interrogative journey, questioning the myths that Iranians are told.

Cici Peng

26 Oct 2022

In a beautiful scene in Jafar Panahi’s new film No Bears, Jafar (playing himself as a filmmaker) encounters an old man in the village where he’s residing, en route to his destination. The man stops him and invites him in for a cup of tea in the waning light. He says that he will accompany Panahi to his destination afterward for safety reasons as there are bears in this Iranian village. Later, when Panahi sets off again, lit against the streetlights, he asks about the bears. The man scoffs, “You know very well that villagers are different from city people. Town people have problems with authorities. We have problems with superstition. There are no bears. Nonsense! Stories made up to scare us! Our fear empowers others.”

Herein lies the film’s central point. The filmmaker dissects the myths we are told to internalise as facts, that we often fail to challenge because of the fear they incite within us. No Bears questions the existence of outdated traditions that separate communities rather than unite them; it questions, above all, how the subordination of women and superstitions of sexual control form the fundamental pillar of political oppression.

There are few filmmakers who lay bare the power of images and their ability to bear witness as well as Jafar Panahi. Throughout all his works, he blends fact and fiction, creating poignant works of personal and political cinema that examines the reality of life in Iran. Panahi’s films are beams of light that illuminate a world shrouded in the shadows of fear and repression.

With the current female-led revolutionary movement in Iran right now, incited by the brutal treatment of Mahsa Jhina Amini over her ‘bad hijab’, we see women not only claiming their individual freedom but fighting for a different Iran for all. Panahi’s film is an urgent examination of the shackles that have bound the country’s people while they fight for freedom. In 2010, Panahi was charged with collusion, propaganda and threatening national security and was sentenced to a 20-year ban on filmmaking. Despite being banned, he’s found creative ways to make potent works of cinema that often uncover how the mechanics of authoritarian power channel their ideology. At the time of this writing, Panahi has been arrested and ordered to serve a six-year sentence as Iran cracks down on dissident filmmakers.

In No Bears, Jafar Panahi plays himself, as a fictional film director who is banned from leaving Iran. Panahi’s character is directing a film over Zoom from a rural village on the edge of the Iranian and Turkish border, close to the film’s shooting location in the neighbouring Turkish town. Even though he can’t be in the physical location, he feels that being in proximity to the film is important and gives him a sense of control despite the often-failing internet connection. The film-within-a-film that Panahi’s character is remotely directing traces the story of two exiled anarchic Iranian lovers, Bakhtiar (Bakhtiyar Panjeei) and Zara (Mina Kavani), who plan on escaping to Europe on stolen passports. As we later learn, the two actors are actually playing lightly fictionalised versions of their own stories and their real attempts at escape. By playing with fact and fiction, Panahi asks you to question reality and what you see rather than watch passively from your screen. By watching Zara and Bakhtiar play themselves, we see how the director asks them to modify their actions. The truth sometimes lies in the gaps between what we can’t see on screen. From the get-go, Panahi asks his viewers to be critical, to distance themselves, and to question narratives, whether that’s here or those narratives forced onto us by the state.

“Panahi asks his viewers to be critical, to distance themselves, and to question narratives, whether that’s here or those narratives forced onto us by the state”

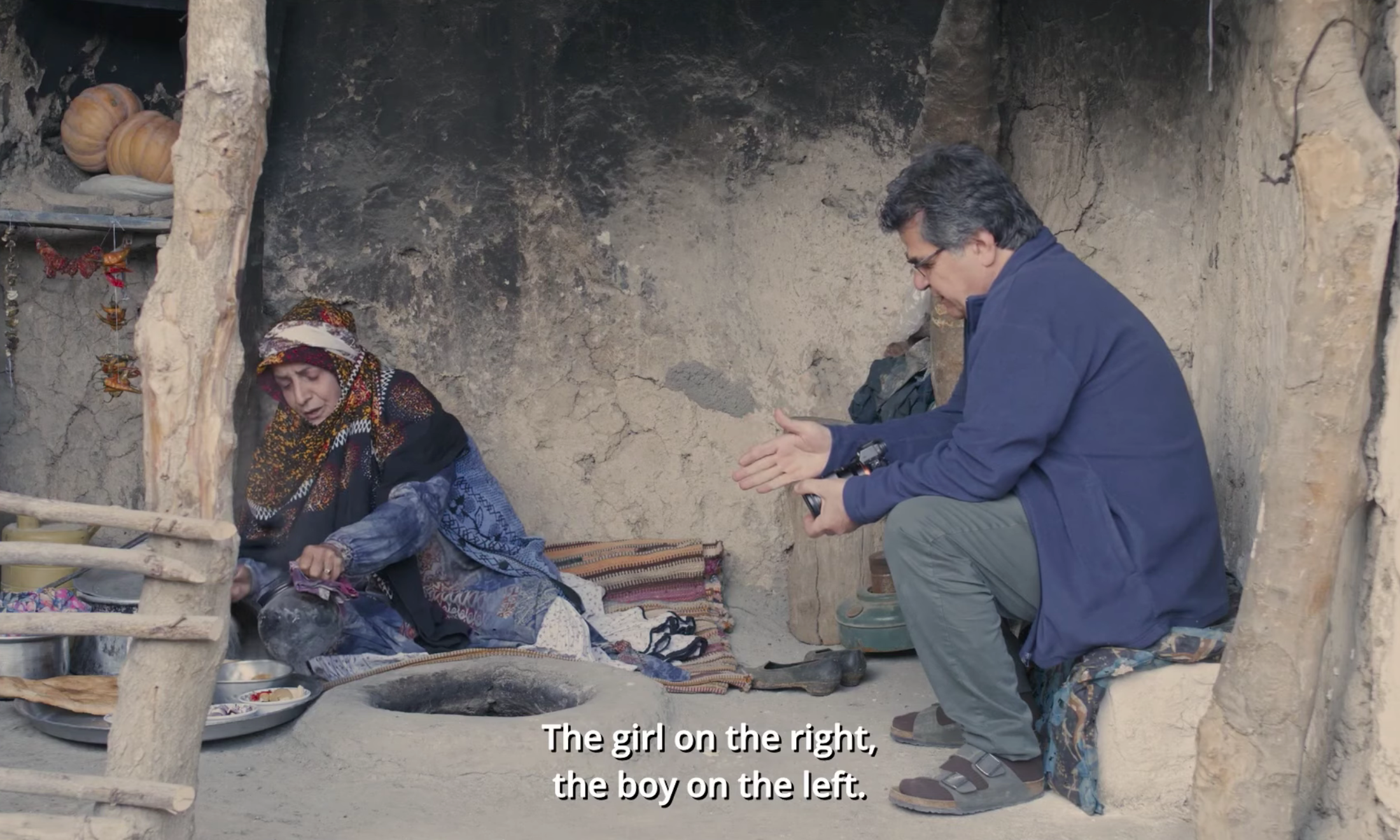

Meanwhile, another drama unfurls in the village where Panahi is residing. In moments of calm between directing, he wanders around the village, snapping photographs of the local kids. However, Panahi finds himself embroiled in the middle of a community scandal when he’s falsely accused of taking a photograph of a forbidden relationship between a young man Soldooz (Amid Davari) and a woman Gozbal (Darya Alei) who is already betrothed to someone else. She already ‘belonged’ to her future husband from the moment her umbilical cord was cut in his name. Facing a community trapped by its customs, Panahi is forced by the local sheriff to give an oath in the village court to confess that this photograph has never existed in order to keep the peace.

The power and danger of images in No Bears is evident – they can bring clarity, but can also be used as incontrovertible and damning proof. A photograph has the power as Susan Sontag writes, to “turn people into objects that can be symbolically possessed”. The village’s fixation on the photograph exposes the underlying need for sexual control over Gozbal’s body, to put her back in place to maintain a hierarchical order that tenuously keeps the peace in the village. A woman’s body becomes an ideological site through which systems exert their power, abstracting her body as property, where she is not even allowed to participate in the court’s dialogue about her future. Instead of examining the arbitrariness of their superstitions and questioning their necessity, the villagers choose to distract themselves by obsessing over the photograph, rather than reimagining the future and the positive potential of change and freedom.

Similarly, in the parallel tale, when they’re filming the fictional final scene of Zara and Bakhtiar’s bid of escape, which – unlike their ‘real story’ – ends with their characters’ successful departure, Zara breaks down. “We’re in this mess so you can create your happy ending,” she cries, pulling off her wig and disguise, addressing the camera, Panahi, and us directly. “But this is all fake.” Refusing to be misinterpreted, Zara breaks the confines of the director’s own storytelling desires to assert her truth. By questioning the authenticity of the film-within-a-film, Zara’s resistance exposes how happy endings often hide the ugly, untidy truths of real life to satisfy viewers at the cost of covering up political injustice.

As viewers, we can no longer hide behind the comforts of a happy ending as we watch. In Iran, we see women taking control of their life and deciding their own reality, defiantly refusing the reality imposed on them by the rogue state. By challenging and questioning the status quo, we imagine and create new futures, one in which we can strive to write our own stories. The women refuse to let their fear empower the theocracy, and instead, look hopefully to a future, and empower others with their fearlessness.

The contribution of our members is crucial. Their support enables us to be proudly independent, challenge the whitewashed media landscape and most importantly, platform the work of marginalised communities. To continue this mission, we need to grow gal-dem to 6,000 members – and we can only do this with your support.

As a member you will enjoy exclusive access to our gal-dem Discord channel and Culture Club, live chats with our editors, skill shares, discounts, events, newsletters and more! Support our community and become a member today from as little as £4.99 a month.