Artwork by Panteha Abareshi

Panteha Abareshi’s art shows what it’s like to be chronically ill in the age of health anxiety

These evocative works chart the 20-year-old’s relationship with her body, the pandemic, and the ableist ideas of what it means to function.

Kemi Alemoru

21 Jul 2020

When the pandemic hit and the US went into lockdown, Persian-Jamaican artist Panteha Abareshi, 20, was already sick. But she didn’t have coronavirus. Since childhood, she has been coming to terms with the impact both sickle cell and sickle beta zero thalassemia have taken on her body. “I was having a health crisis, it was so bad,” she explains over the phone. Her father drove to Los Angeles to pick her up and take her to her family home in Arizona to take care of her.

Seeing how quickly the world changed when people were scared they may experience severe illness was “jarring”. Suddenly society could understand conversations around accessibility, health and safety in schools, museums and more. Programming changed to be more inclusive for those who couldn’t physically attend.

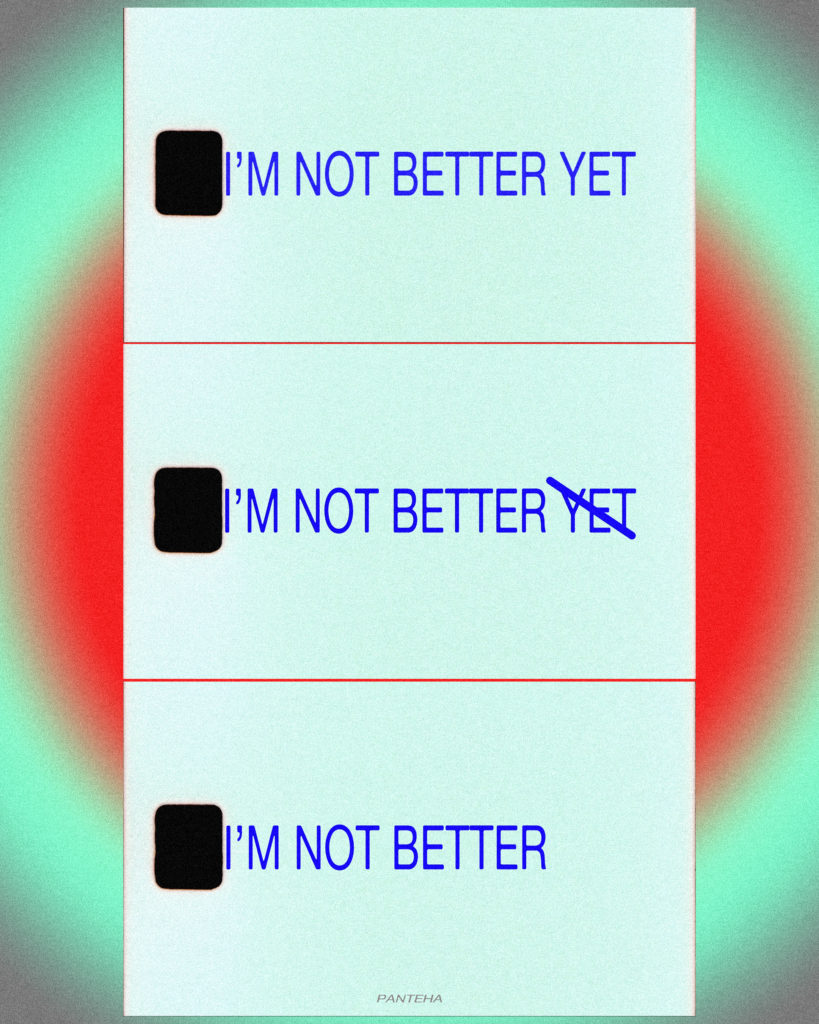

However, she feels it is only to aid people who rarely have to think of missing out. “Able-bodied people are suddenly thinking more about their own health in a more frantic state,” she adds. But when the dust settles on this chapter, or if a vaccine is found, this doesn’t mean these things are no longer needed or that health anxiety can subside for those with chronic illnesses and disabilities. “We don’t teach awareness of illness and disability at all. It’s not built into the way people think about others, it’s not built into the language that we have.”

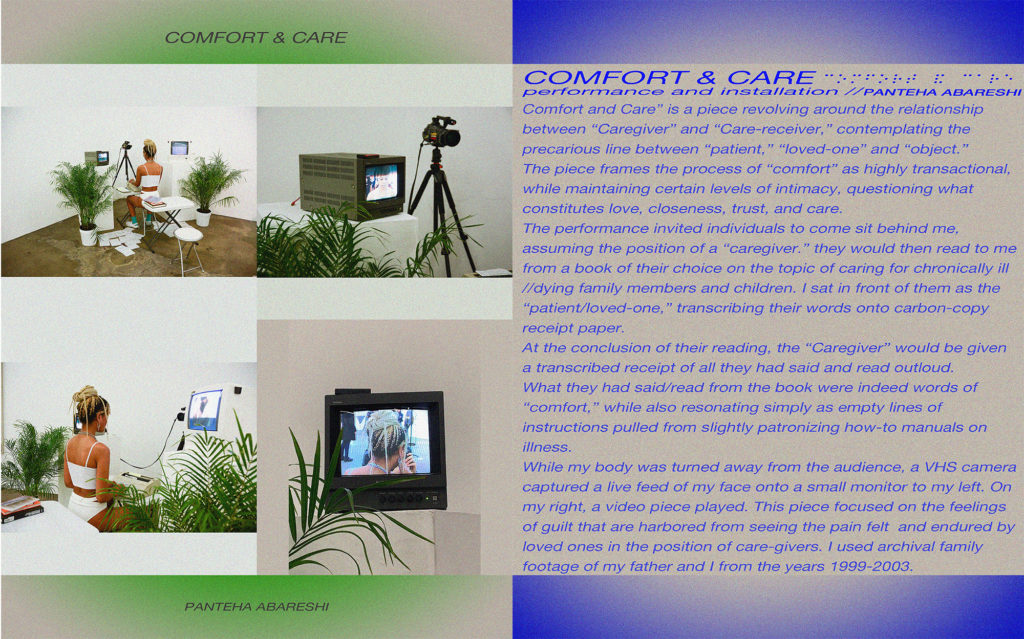

Panteha’s art aims to illustrate the realities of coming to terms with these difficulties. Despite being only 20, she speaks with worldly-wise conviction. Academically bright and well-read, she refers to a breadth of theories throughout our conversation. But she didn’t get to go to high school much due to her illness. Instead, she fine-tuned how to express her new reality, creating thought-provoking art that has earned her the cover star slot of Bitch magazine, and, in October of last year, presented her solo exhibit HIPAA VIOLATION at the Lindhurst Gallery within the USC Roski School Of Art.

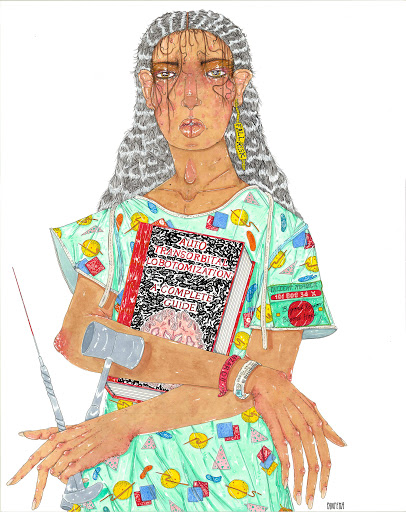

Initially, she specialised in vivid, saturated and visceral illustration as a coping mechanism when she was in hospital in her teens. “It was all 2D work on paper. My illustrative work was all very literal, mostly bodies in immense amounts of pain. I was literally drawing how I was feeling,” she explains. Her health conditions often lead to “pain crises” that are debilitating. “I’m always in a baseline of pain every day. A good day means I can walk and function at a low level. I can stand with a cane,” she says. “But all of a sudden it will get so bad that I can’t move my body on my own.” The multi-disciplinary artist’s recent crisis meant her father had to move her arms and legs and reposition her body for circulation. Then there is the “domino effect” of illnesses that result from her genetic conditions which cause issues with her joints and mean she needs hip replacements and spinal surgeries. Despite the fact she’s been experiencing symptoms since childhood, it has been steadily getting worse since she was 14 and is likely to worsen with age. “Sometimes I can’t even articulate words,” she adds.

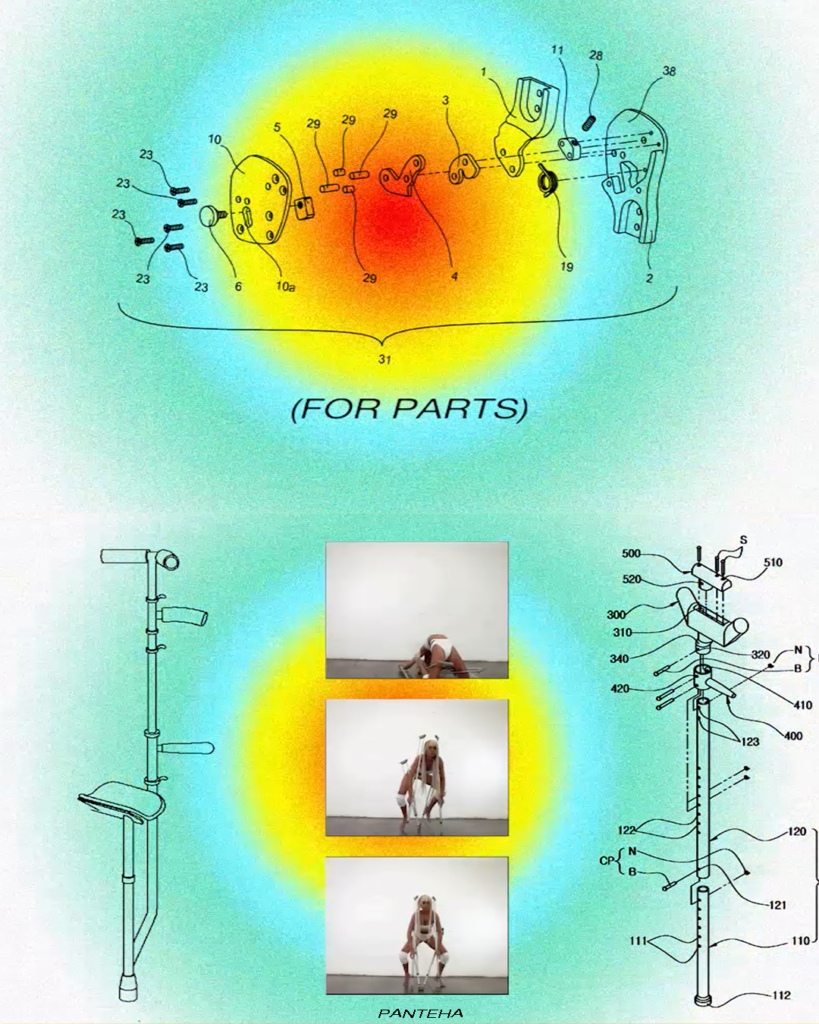

That’s why she’s finding a variety of mediums to communicate her ever-changing reality. She has turned to photography, performance and films of late. In one image, Panteha dons a mask to cover her face and two more to cover her breasts as she comes to terms with the idea that “while one quarantine might come to an end soon, mine is stretching on indefinitely”. Her short film, Natural Disaster, shows her impressively contort her body while balancing on top of a wheelchair, her joints bandaged. “My practice is different because I’m in a different place with my illness where I accept it. I’m using my body as the medium,” she explains.

Although she still finds it frustrating and scary she’s OK with being in pain – something that unsettles audiences. The act of incorporating contortion into her imagery puts her physical pain on display. Her clips are spliced between images of wildfires and other destructive natural phenomena and quickfire text that sums up her own feelings: “This biological chaos is unrelenting”.

Looking at her latest 8mm film, which was shot on VHS, Panteha appears bandaged and writhing on an operating table, to symbolise how she often feels out of control of what her body does from one day to the next. In other scenes, she’s hooked up to a machine with a target on her back which is a recurring theme in her new projects.

“I’m no longer an organic body and I no longer adhere to a lot of what defines being human. They’re ableist standards”

Increasingly, the presence of tech, gadgets, screens and old monitors encroaches on her vivid scenes. “What spurred me on this path is that I got a hip replacement and I have a [medical device] in my chest. I was 15 or 16 and when I first woke up from the surgery I had this metal thing under my skin and I had wires and tape connected to my heart. It was the first time I had an immovable mark of illness on my body,” she says. After reading The Xenofeminist Manifesto, a political book which explores the potential of tech for both its tyrannical or emancipatory possibilities, she became interested in the idea of embracing “becoming a cyborg”.

“It’s the radical notion that that is the next step in evolution. These pieces of metal are what holds me together. I’m no longer an organic body and I no longer adhere to a lot of what defines being human. They’re ableist standards,” she says. “Everything in medicine is trying to imitate the able body and I’m tired of it. Prosthetics are so taboo and even though it is trying to imitate the function and look like the body it is still not seen as the body. It’s a lose-lose game.”

Just as her health increasingly impacts her day-to-day, with each project Panteha’s point of view is sharper and more urgent. She tells me that people speak about illness as if you’re waiting to get better, but in many ways, her art is defiantly resistant. For her, there is a power in acknowledging that things won’t be a return to health and that she shouldn’t have to put her life on hold because of how other people believe sick people should behave. Weaving in metaphors that illustrate her own relationship with the human body, and nature itself, she’s cataloguing what it’s like to be chronically ill and challenging the ableist idea of what it looks like to function.

View more of Panteha Abareshi’s work below.