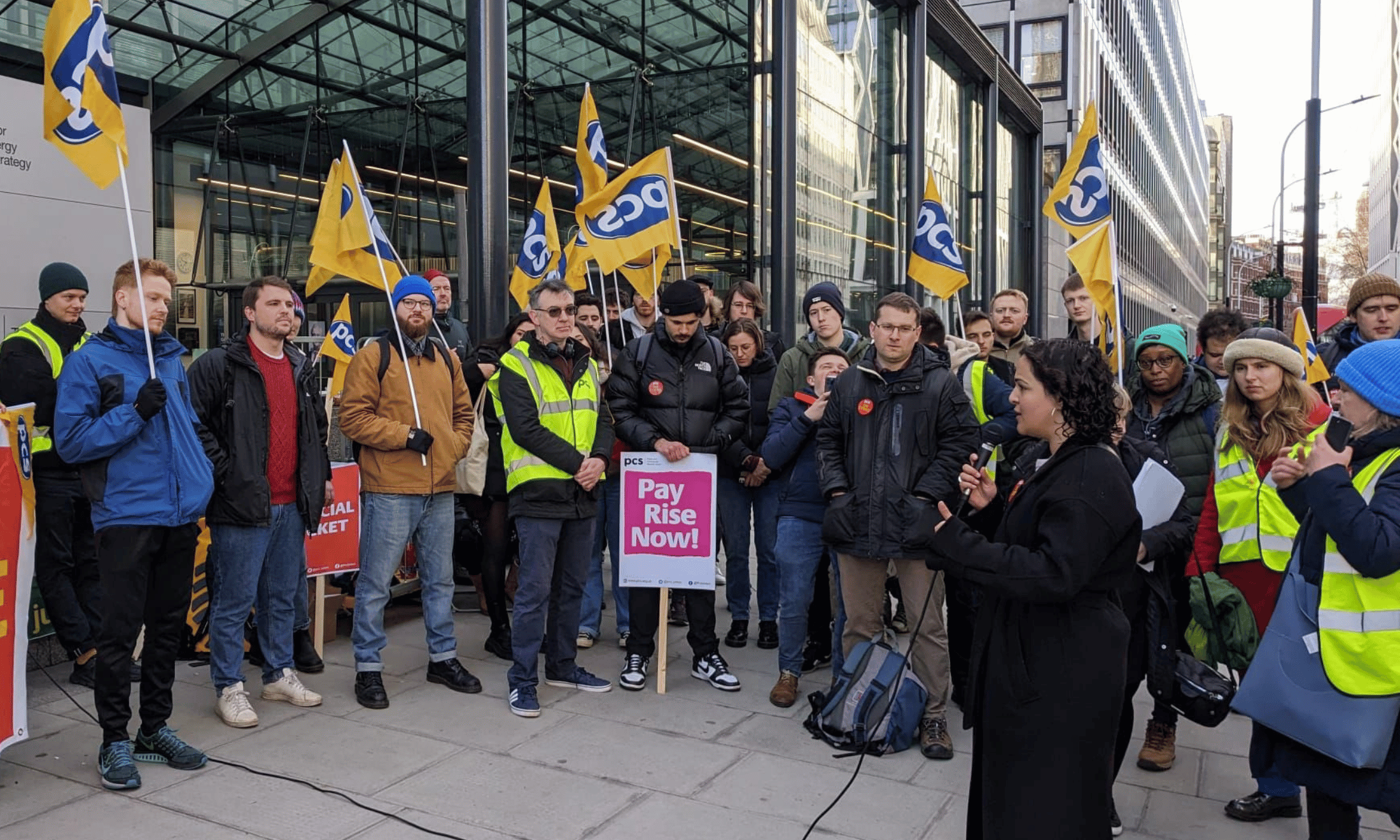

How this Manchester group is winning their fight to keep police out of schools

For northern group Kids of Colour, 'safer schools' are ones free of a police presence.

Kimi Chaddah

25 Feb 2022

India Joseph

It is June 2021, and billboards are cropping up in the colourful streets of Manchester, compelling passers-by to pause. Adorned with the ‘No Police in Schools’ logo and illustrating a police officer torn in half with their back to the school, they read “young people need support not suspicion”.

The signs are part of the No Police in Schools campaign – a collective community campaign between Kids of Colour, Northern Police Monitoring Project and the NEU’s Northwest Black Member’s Organising Forum. Established in 2018 by community organiser Roxy Legane, Kids of Colour acts as a safe space for young people of colour aged 24 and under to speak openly about challenging the status quo, institutionalised racism and build less carceral and more ambitious structures of education. From running summer schools and workshops to offering support to individuals experiencing institutional racism, Kids of Colour acts as a safe space for children to envision police-free futures.

“From running summer schools and workshops to offering support to individuals experiencing institutional racism, Kids of Colour acts as a safe space for children to envision police-free futures”

Racism is deeply embedded in the education system – exemplified by stark disparities in school exclusions and uniform policies, to lunchtime food. The experience of marginalised communities in school environments can be defined by a sense of being unfairly penalised. Now, the presence of police in schools openly enables state-sanctioned racism and reinforces pre-existing inequalities.

Formed in response to plans to bolster police presence in schools, the No Police In Schools campaign ‘officially’ launched in 2020 after the Northern Police Monitoring Project and Kids of Colour spent a year listening to emerging stories of police presence in schools. In February that year, the “Serious Violence Action Plan” put forward by Greater Manchester mayor Andy Burnham, revealed plans to put 20 additional police in schools for the 2020/2021 academic year, prompting the campaign to schedule their first organising meeting in March.

Endorsed by Burnham, the move represented an increase to the existing presence of police officers in schools across the country – currently, police forces deploy 683 officers in schools across the UK. In response to the Guardian, the London Metropolitan Police added that they sometimes utilised data detailing numbers of deprived children to choose “priority schools” across the capital to receive more intensive interventions, with metrics used by the Met police including the “provision of free school dinners (as an indicator of social deprivation)”, as well as GCSE attainment rates, crime data linked to schools and persistent absence levels – as well as the number of children with allocated social workers.

“Currently, police forces deploy 683 officers in schools across the UK”

Once again, poor and working class areas were targeted by the Met police; areas with less resources to confront institutions of power. But this wasn’t just limited to London – many of the 683 officers were reported to be assigned to places of high deprivation across England, including Oldham in Manchester, where levels of deprivation across the borough are ranked among the highest in the country. Campaigners argue that the placing of police in schools perpetuates a culture of hostility and suspicion, policing not only students, but potentially teachers. “It creates this stigma around schools, and [for] the young people within those schools,” says Roxy Legane. “[They] feel that ‘we’re young people who need policing’”.

In situations where intervention is needed, Roxy says that community expertise should be involved. “Schools should be reaching for educators who come into the school, talk to young people involved and support those who are harmed. But what you see as an alternative is police walk[ing] in, and a criminal record or something on [a child’s] file – a real acceleration”.

The scheme to increase police presence in schools espouses the belief that police officers would become “figures of trust” (according to Burnham’s Serious Violence Action Plan published in 2020) who challenged ‘entrenched’ pro-crime attitudes, operating under the illusion policing within schools will “build positive relationships” between young people and police. The root causes of behavioural issues and youth violence – often things like poverty and toxic environments – are largely ignored, as well as the impact of school funding cuts.

“The root causes of behavioural issues and youth violence – often things like poverty and toxic environments – are largely ignored, as well as the impact of school funding cuts”

Under the scheme, minor disciplinary issues previously dealt with internally – either via school support officers or teachers – are assigned to police officers, changing the dynamic in the teacher-student relationship, and foregrounding a hierarchy. Non-issues suddenly become issues. “I don’t think there’s a need for police in schools,” a 13-year-old student in Manchester tells gal-dem, “because all ours really did was shout at children who were late.” [All interviewees associated with Kids of Colour have been placed under anonymity to protect their identities].

The positioning of police as ‘skilled’ interventionists reflects the enduring myths that underpin police power and aligns with the framing of police as an answer to social issues, from problems in the education system to mental health services. There are palpable fears it could lead to the criminalisation and state surveillance of young people of colour by knowingly placing marginalised communities in close contact with the criminal justice system and strengthening the school-prison pipeline. It plays into the wider trope of young Black people being stereotyped as gang members and consistently targeted by police as a result – more than half of young people in youth custody across the UK are Black, or from ethnic minority communities.

“My most vivid memory of interaction with police in schools was when I was called out of the classroom by an officer,” a 19-year-old Black student tells gal-dem, “without any type of warning and without my parents’ permission. I was informally interviewed without any teacher or guardian and told ‘that people like me end up in prison’ before being told ‘I could (hand)cuff you right now, but won’t,” they continue.

“My most vivid memory of interaction with police in schools was when I was called out of the classroom by an officer, without any type of warning and without my parents’ permission”

In November 2020, the No Police in Schools campaign gained momentum, with boroughs including Trafford and Oldham pushing back and passing motions for no police in schools. For the coalition, Roxy says support from the National Education Union, particularly members of the NEU’s North West Black Members Organising Forum was “invaluable”, helping young people realise “that teachers were on their side”.

Just three months before Oldham, Trafford and Manchester NEU district members passed motions for no police in schools, the campaign produced the Decriminalise the Classroom report – compiling responses from 554 young people and adults detailing the negative impacts of police presence in schools in the area. Among the pages was the reminder of state violence, with police violence against women present from schools to the streets: young women who informed the report stated they were called ‘sluts’ and victim blamed by their school-based police officer (SBPO).

Greater Manchester Police itself has faced scrutiny for its record on race. Last year, a report commissioned by Burnham branded it ‘institutionally racist’, finding that Black people were four times more likely to have force used against them in comparison to white people, and 5.7 times more likely to be tasered. While furiously rejecting the allegation of institutional racism, Chief Constable Stephen Watson admitted it was likely the force could feasibly employ “somebody who behaves in a racist way”.

In July 2021, Manchester Council quietly scrapped the Mayor’s plan for police officers in schools, with active police officers being redeployed into different areas. Roxy expresses relief at one notoriously harsh police officer at a child’s school, aged 13, being removed because of the campaign. In a report compiled by the No Police in Schools campaign, accounts of the officer’s behaviour at Wright Robinson College include zealous overpolicing of attendance, hairstyles, and overt discrimination based on arbitrary behaviour (from Black students being questioned while walking in a corridor or standing in a group, to being surveilled on social media and in the school environment itself). But campaigners are still wary that the current ‘solution’ is no utopia.

“In July 2021, Manchester Council quietly scrapped the Mayor’s plan for police officers in schools, with active police officers being redeployed into different areas”

“We don’t want to undervalue that as a win at all,” says Roxy. “It wouldn’t have happened without the pressure we put on those in decision making roles”. Yet, “it’s still a damaging approach because police officers still have access to the same intelligence,” she continues, with local authorities refusing to divert from this new approach which is still rooted in policing. The approach, while focused on multi-agency hubs outside of the school, will “still see all these agencies (including the police) come together to share information on young people, including educational staff,” Roxy explains.

“So the alternative – while they’re not inside the school gates and beyond being able to handle that intelligence (by implementing social work meetings or school decisions) – is also another challenge”.

Roxy points out that the ‘official’ policy surrounding policing in schools nationally is unclear, and stresses the importance of resisting its wider implementation. In September 2021, a police officer who was part of a “safer schools” unit avoided a prison sentence after CCTV caught him dragging a schoolboy with autism along a floor by his coat hood after the child tried to escape from him “in fear”. The incident – for which the offending officer was only fined £800 after being found convicted of assault – typifies a worrying lack of regard for vulnerable children from those supposedly keeping them safe.

London Mayor Sadiq Khan has called for more police in schools to stop a “post-lockdown violent crime surge” – yet last year, Avon and Somerset police were criticised for their ‘heavy-handed’ treatment of a 12-year-old mixed-heritage pupil at a school in Bristol. Alex*, as the student has been identified in reporting by the Guardian, had been in Year 7 for less than two weeks when he was wrongly accused by a teacher of having stolen cookies from the canteen at lunchtime. He was left ‘petrified’ after a teacher asked a police officer to speak to him.

“For young people of colour, the presence of police in schools doesn’t reflect a possibility in the future – but reality”

The fight in Manchester against police in schools isn’t over either, despite the official end of the policy. Just last month, a group of parents notified the campaign that an officer was being placed in their children’s school once a week, with a week’s notice. “We need those local connections and that local intelligence,” Roxy says, “to inform our organising and support”, as well as resistance.

For young people of colour, the presence of police in schools doesn’t reflect a possibility in the future – but reality. Sustaining the momentum amidst a backdrop of the Police, Crime and Sentencing Bill is crucial to forcing shifts in the system, and the precedent it sets reflects how the movement towards uprooting the system is local and global. Kids of Colour may have claimed an initial victory in their first battle, but the war to carve out an alternative – and more hopeful – future is far from finished.

Like what you’re reading? Our groundbreaking journalism relies on the crucial support of a community of gal-dem members. We would not be able to continue to hold truth to power in this industry without them, and you can support us from £5 per month – less than a weekly coffee.

Our members get exclusive access to events, discounts from independent brands, newsletters from our editors, quarterly gifts, print magazines, and so much more!

Britain’s policing was built on racism. Abolition is unavoidable

How Pakistan’s Khwaja Sira and transgender communities are fearing and fighting for their futures

Their anti-rape performance went viral globally. Now what?