Photography courtesy of Leah Cowan

Portrait of a lady on fyah: how come selfies are narcissistic but self-portraits are highbrow?

Felt cute, won't delete later. It's time we acknowledged that a cheeky selfie is actually a vehicle for self-expression and liberation.

Leah Cowan

08 Jun 2020

One of the oldest known self-portraits is attributed to Bak, chief sculptor-about-town during the reign of the Egyptian pharaoh Akhenaten. A carved quartzite slab now sitting in the Egyptian Museum in Berlin depicts Bak and his wife Taheri; they are standing side-by-side and she has her arm around him, possibly the earliest #couplegoals on record. Bak was ahead of his time. It wasn’t until the mid-15th century that, thanks to mirrors becoming more available, many of the Old Masters turned to their own pallid jowls for source material. Evidently, self-portraits move through different modes and mediums depending on fashions and available technologies.

Fast forward to 2013 and the word “selfie”, meaning “a photograph that one has taken of oneself”, is selected as Oxford Dictionaries’ Word of the Year. Surely, such formal recognition led to some selfies being elevated to masterpiece status and afforded gallery space, and whole PhD theses being written unpacking the nuances of filters and the advent of the ring light, right? As you’re probably aware, this wasn’t the case. Since their very inception, selfies have been roundly derided and dismissed as yet another silly thing millennials do instead of becoming a middle manager and getting on the property ladder.

Gender plays a key role in this dismissal. A brief history lesson helps us understand why: from Renaissance painter Albrecht Dürer, whose filter of choice was to depict himself as Jesus, to the Dutch post-Impressionist Vincent Van Softboi who served looks in a striking straw hat, many of the most well-known self-portraits are, of course, by men. While women and women-presenting artists were also prolific self-portraitists, their work is less well-known and showcased, because… patriarchy. During the Renaissance period, women were not allowed to attend life-drawing classes, despite the fact that women’s bodies were commonly depicted in men’s paintings, after being wrung through the tedious assault course of the male gaze. Because of this barrier to their training, women artists often turned to self-portraiture in order to learn more about anatomy.

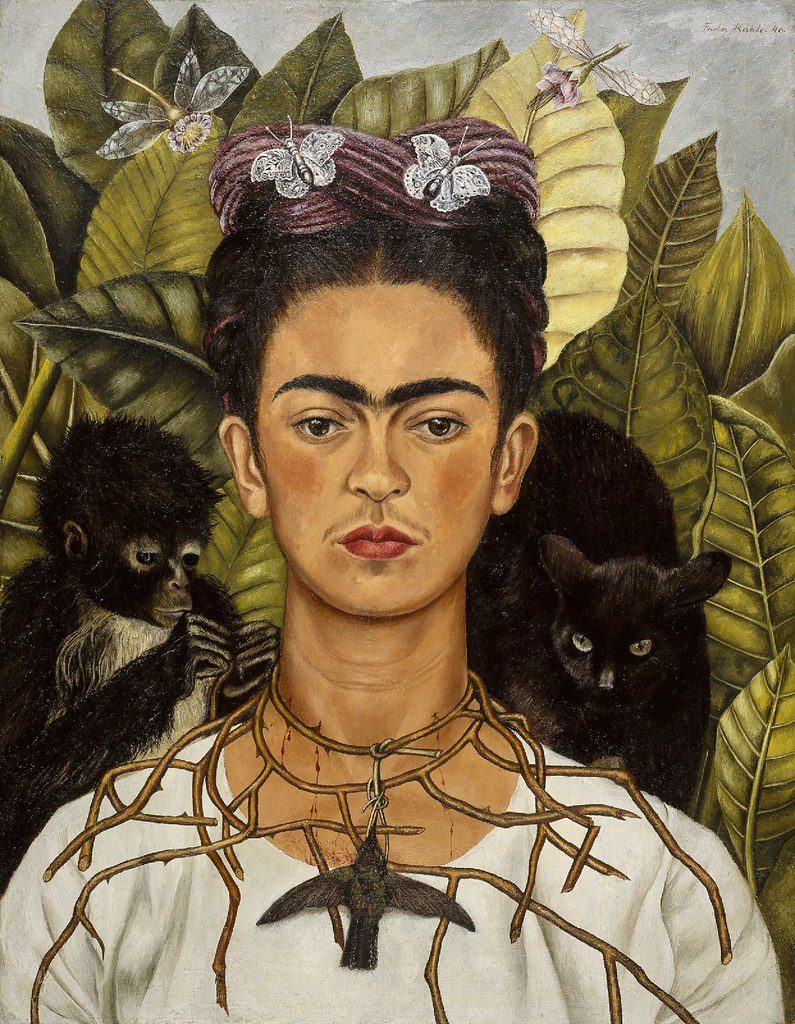

Self-portraiture also became a way that women and other marginalised artists could express themselves, and quite literally “be seen”. Notable self-portraits have been made by gay Renaissance painter Giovanni Antonio Bazzi (also known as Il Sodoma, a nickname he reclaimed for himself) in the 16th century, gender non-conforming artist Claude Cahun in the 1920s, Mexican painter Frida Kahlo in the 1930s, and African American painter Loïs Mailou Jones in the 1940s, who held her first solo exhibition aged just 18. This impulse to depict ourselves is particularly important for people of colour, who have been invisibilised throughout the history of art (such as in Claude Lorrain’s 1648 whitewashed “Queen of Sheba”), pushed to the edges of the frame or the back of the composition, as we see in Manet’s 1863 painting “Olympia”, or exoticised through a racist and colonial lens, as in basically all of Paul Gauguin’s paintings, made during his travels in Tahiti, during which time he also married three young girls. Self-portraiture, then, acts an important tool for reclaiming our own image. As Audre Lorde famously said during a speech at Harvard University in 1982: “If I didn’t define myself for myself, I would be crunched into other people’s fantasies for me and eaten alive.”

“Self-portraiture acts an important tool for reclaiming our own image”

Knowing this context, it shouldn’t surprise us that selfies – a no-cost form of self-expression largely popularised by women and femmes – are dismissed as either vapid, narcissistic, a symptom of low self-esteem and absence of intimacy, or a manifestation of consumerism showing up as individualism and the need to perform perfection. The effort driving this body of criticism reveals that selfies do not nestle comfortably into the patriarchal masterplan. A whole load of boring sexist and heteronormative discourse around selfies attempts to suggest that selfie-takers are insecure and seeking external validation. This jars with my largely anecdotal hypothesis that the vast majority of selfies don’t get posted online. I’d wager that most selfies simply sit quietly in private albums on people’s phones. They are scrolled through from time to time for a quick reminder of aesthetic excellence, much like dusty old dukes who had oil paintings of themselves hanging in their bedrooms.

Along with the degradation of the art form, the poses that come with it are similarly derided. The term “duckface” was coined to mock the pout adopted by many selfie-takers in the mid-2000s, which was often paired with the ‘Myspace angle’, where the photo is taken using a camera clutched in an outstretched hand from a height. The level of disdain for duckface illustrates the hoops that women and femmes of colour have to jump through as we navigate both online and offline public spaces. The paradoxes are tired but relentless: we must “make an effort” but not “try too hard”, and also always remember to smile because “it might never happen” but don’t smile too much in case it seems forced. Heaven forbid we pull a face, take a photo and it not stir the loins of every incel frothing at the mouth on Reddit. Bizarrely, vast swathes of the internet are dedicated to mocking people (again, mainly women and femmes) who get injured or die taking selfies. However, accidents in other equally playful forms of self-expression such as graffiti and parkour (scenes largely dominated by men) are marked as impressive near-misses or solemn tragedies.

“Heaven forbid we pull a face, take a photo and it not stir the loins of every incel frothing at the mouth on Reddit”

We can only speculate why different types of self-expression are categorised as high- or lowbrow, but common themes seem to be that art created on and for low budgets, by and for working-class people, women and femmes, LGBTQI+ people, people of colour, and other marginalised groups are looked down on by the cultural elite. Key examples of this are the way that pop culture (especially soaps) is often deemed vacuous or “trashy”. Meanwhile accessible internet culture including memes, fan fiction, Twitter threads, YouTube and Tumblr communities and viral videos are often depicted as being ersatz or lesser forms of, for example, film-making, art, literature, activism, and cultural and political commentary.

The demonisation of selfies as nothing more than millennial navel-gazing is another example of a snobbish, ageist double-standard, in which the hubris of a bumbling white old-money prime minister is “confidence”, but the self-assurance of a working-class woman-turned-celebrity such as Coleen McLoughlin makes her, according to The Sunday Times, “a ‘superchav’, the uncrowned queen of chav.[…] A girl of average looks, an unremarkable figure and no discernible talent…” The classism jumps out in the mainstream media’s derision of working-class people whose images become visible and who choose to be “seen”. It makes sense that Coleen’s curation of her own image, outside of the upper-class symbols of success, would rile a Sunday Times journalist to publish such vitriol about a working-class woman quietly securing the bag.

Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird (Autorretrato con Collar de Espinas), 1940

The idea that there is an inherent difference in quality between so-called lowbrow and highbrow forms of art and expression is rendered false when we recognise that, as philosophy Professor Alex King explains, the meaning of art shifts over time. Alex writes that “many things that are now high art or highbrow, like jazz or film or beer, used to be lowbrow. […] Following wine’s lead, coffee and beer are the subjects of erudite discussions, and gourmet food stores are exploding all over.” Similarly, we only have to look to moments like what I’ve dubbed “WordArt renaissance” to see forms of expression that were briefly regarded as desirable fall from grace and become naff, before coming full circle and being used again in a “retro” or “ironic” form.

Ultimately the suggestion that selfies are a base form of expression fails to graps how they’re often used as a tool for people to become comfortable with themselves. Anyone who has ever spent a peaceful afternoon in their bedroom lying in a pool of golden-hour light and snapping selfies, most of which you won’t even post, can relate to Frida Kahlo. The icon once said: “I paint self-portraits because I am so often alone because I am the person I know best.” Taking a selfie is also an act of knowing. We know our preferred angle, and we know how to build our image and use filters to relate more warmly to ourselves, including to manage dissonance and gender dysphoria. Foster Rudy, a nonbinary author currently documenting their transition tells Allure that “sharing a selfie feels like an act of personal assertion. I am trans, this is my presentation, you will see me the way I wish to be seen.” Over time I’ve learnt that cis men get in their feelings when we post selfies because they are confronted with hard evidence that we exist as solitary beings outside of their gaze, and that we can choose to see, and be seen, whether they like us or even look at us. Flipping on the front camera returns the gaze back to us.

The ability to depict ourselves as we see ourselves presents an opportunity to play with and present our image outside of the patriarchal gaze, the gender binary, and all of the oppressive lenses which seek to “other” us without our consent. As we capture our image there is a moment of release. In this moment we are no longer letting white supremacy paint the picture of who we are; we can take on new forms and fly free, even if just for that singular photo. Selfie-taking can feel liberating, whether we post them on a public platform or not. Owning and authoring our image, and taking up visual space in a world that wants us to shrink and be mute and invisible (or dead), is a powerful act. Selfies are not just images of the self. Selfies are images for the self, rooted in a long tradition of image-making in defiance of those who do not want us to be visible.

Me, Myself and I is a week-long celebration of self portrait photography focusing on the power of creating art alone.