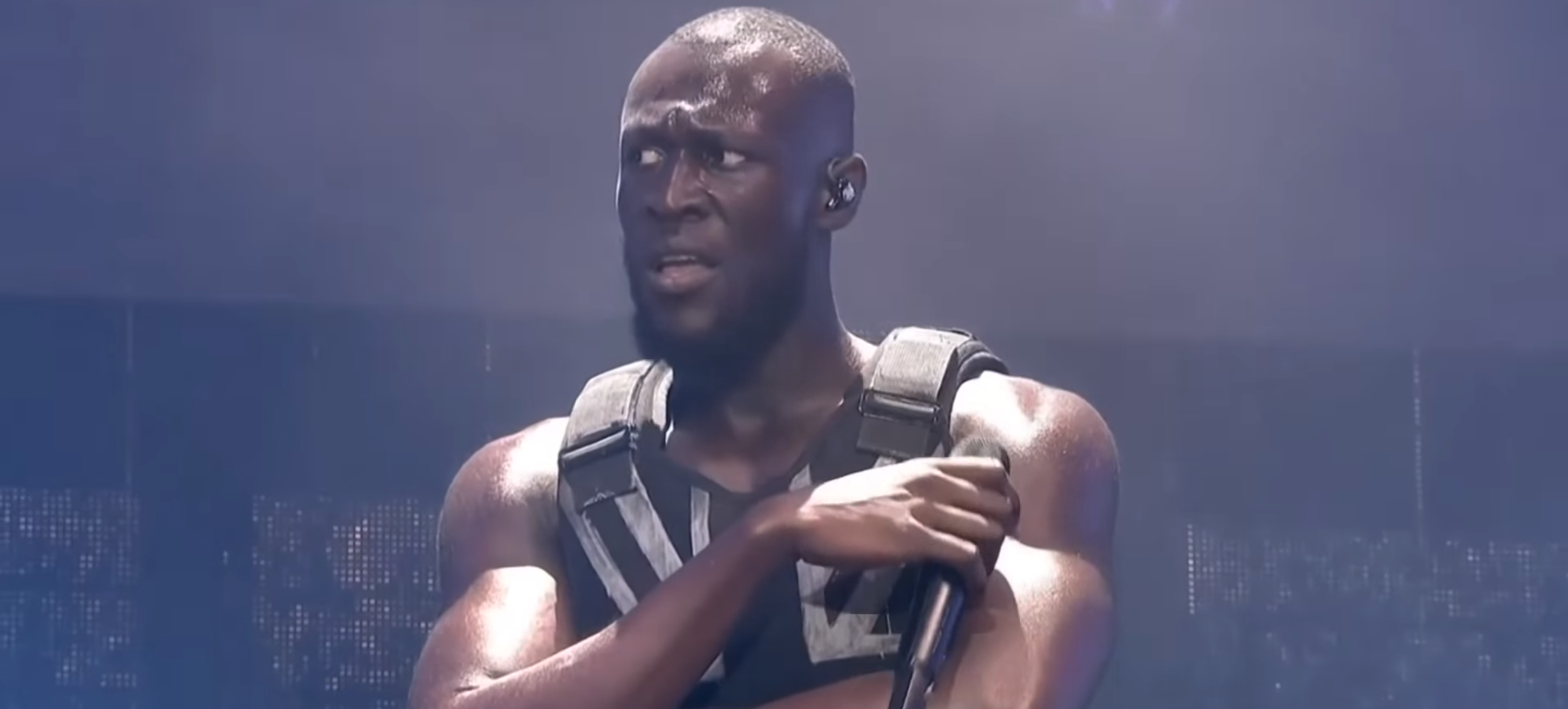

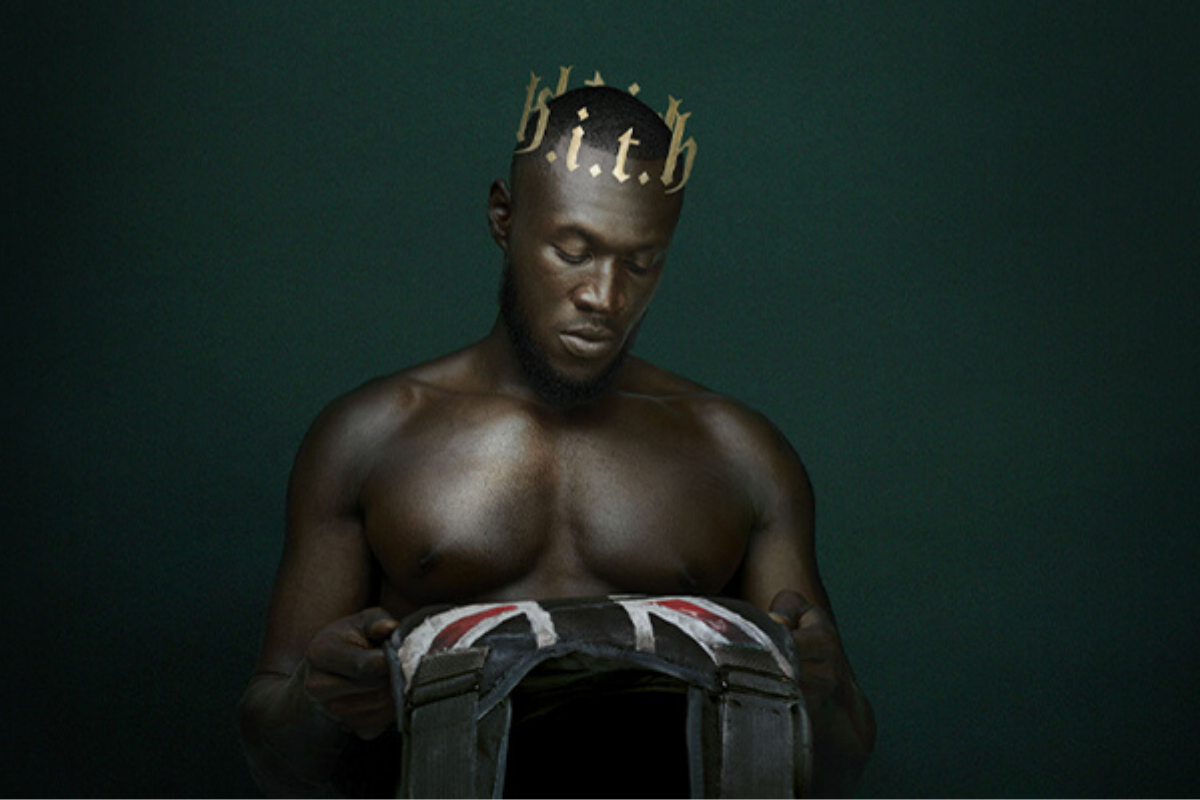

Until recently grime has remained underground. The music subculture that was born in east London received little external recognition, until its entry into the contentiously-regarded mainstream over the past two years. Since then, grime has garnered increasing amounts of attention; artists are topping charts, winning awards and embarking on global tours. Private school kids are donning garms that wouldn’t be out of place on Broadwater Farm circa 2003, while opinion writers insist the genre has been crassly appropriated from its gritty, urban roots. The attention is being further boosted as other mediums buy into the genre. This year, there has been a noticeable increase in grime-centric print products – last week, for example, Stormzy was announced as i-D’s first ever grime cover star.

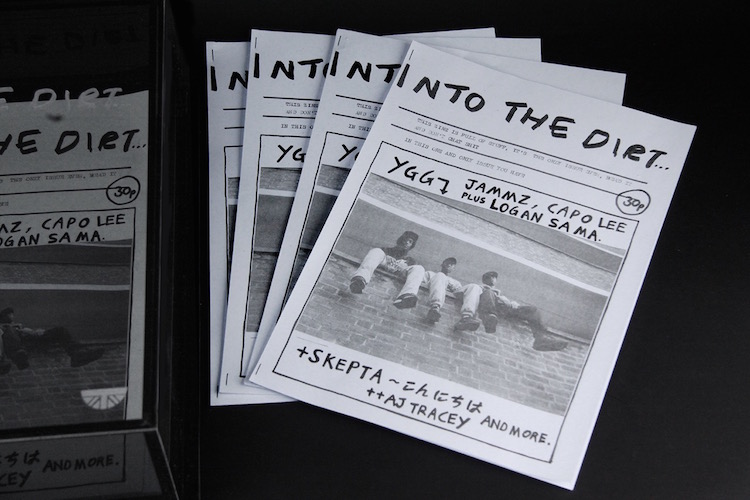

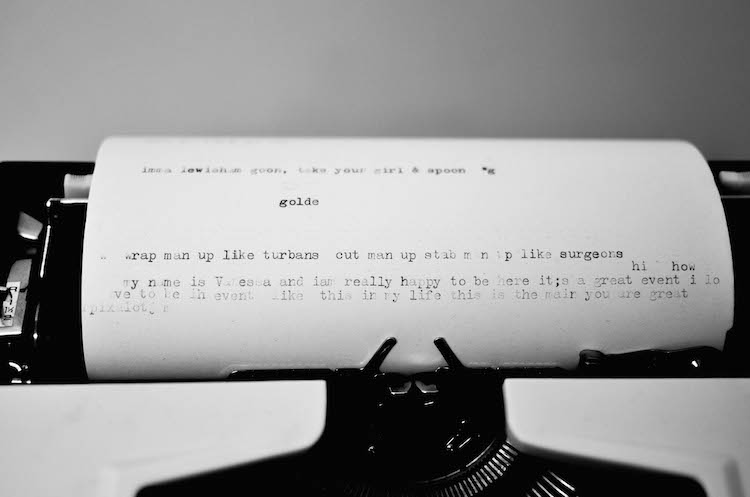

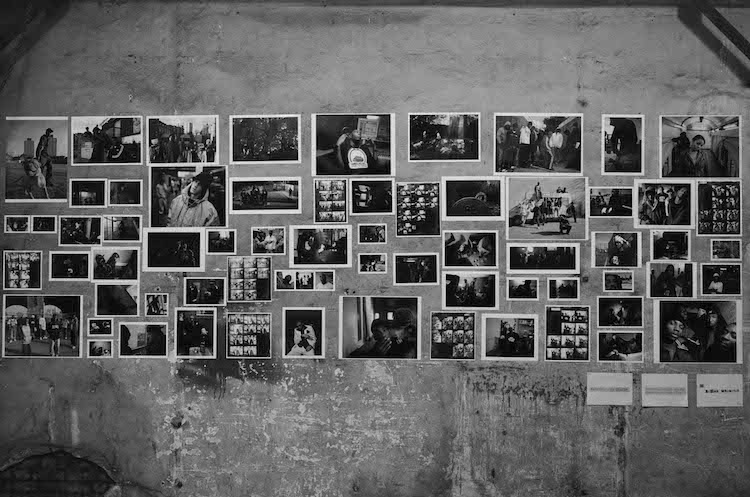

In 2010, the photographer Simon Wheatley released a photo book, Don’t Call Me Urban! The Time of Grime. The book provided a visual guide to the genre and was something of a unicorn at the time of publication. In 2016 though, other titles have joined the bookshelf. Wheatley recently contributed to an eight-part grime zine called Into the Dirt created by Underground. The zine is intended as a snapshot of the contemporary grime scene. Inspired by punk-era DIY print culture, they are typewritten, hand-stapled, black and white booklets containing quality content that contrasts the intentionally slapdash aesthetic. Last month Hodder and Stoughton publishing house released This Is Grime, a compendium of exclusive photographs and interviews giving detailed insight into grime’s backstory, by journalist Hattie Collins and photographer Olivia Rose. The same publishing house has just released the Godfather-of-grime Wiley’s autobiography.

These releases represent a new type of engagement with grime, they resemble a sort of cultural commentary. For a long time the now defunct SASS, out of which came RWD magazine, was one of the only print publications giving grime any time of day. Forerunners like Heartless Crew and Ms. Dynamite featured in RWD while grime was pulling its socks up and Dizzee made front page in 2003, just months before receiving the Mercury prize. As more publications write on the genre, there seems to be a concerted effort to preserve grime’s history.

Print is a means of immortalising grime. Books like Rap Attack by David Toop and Can’t Stop Won’t Stop by Jeff Chang helped to do a similar thing for hip-hop. The latter illuminated the story behind the genre in an intricate (though at points disorderly) manner and today serves as an obvious source of inspiration for the popular Netflix series The Get Down. This year’s grime-focused releases could be the building blocks of a new area within music and subcultural studies and will ensure that grime’s current popularity amounts to more than just a transient fad. “What’s important for me is where grime is coming from, and to record this is to serve the purpose of historical archiving,” says Simon Wheatley, “I have always been interested in the socio-historical context of grime.” The Time of Grime and Into the Dirt capture this context well. Wheatley’s fly-on-the-wall photography apprehends the beginning of something distinct and through it, the visual markings of a subculture can be identified. Fashion is the most striking example; new era caps and name-brand tracksuits are a common thread throughout both publications.

“Initially it was hard to get it published,” he says of his own book, “one publisher mocked that teenagers didn’t have the money to buy hardback books.”

More print is symptomatic of a two-way relationship. As grime becomes a trendy talking point, there will inevitably be more information available on it. Equally though, increasing text on the genre will only validate it further as a worthwhile area of study. According to Wheatley, legitimacy has been an ever-present issue for grime, “Initially it was hard to get it published,” he says of his own book, “one publisher mocked that teenagers didn’t have the money to buy hardback books.” The comment is steeped in assumptions about class and race; it is no secret that grime was established by predominantly working class, black youth so it doesn’t take a genius to decipher just whom the comment was directed at. You may as well read the word “teenagers” in inverted commas and imagine a wink and a nudge along with it. Print represents not just legitimacy, but a kind of perceived social ascension. We made it to the typeset echelons.

Such a dismissive attitude towards grime points towards a diversity problem in publishing. A report published by Writing the Future in 2015 outlined the issue as more than 74% of those employed by large publishing houses and 97% of agents believed that the industry is only “a little diverse” or “not diverse at all”. The less diverse an industry, the less diverse its output. Perhaps if there were more people of colour in publishing houses, grime would have been higher on the agenda a while ago. It is a good thing that grime is gaining recognition in print, but frustrating that a predominantly white industry remains the gatekeeper of legitimacy (just as a predominantly white fan base was necessary for the genre to go mainstream).

Erin, a representative of Into the Dirt zine, agrees that more print suggests a more legitimate perception of grime, but warns that we shouldn’t detract credit from the artists themselves, “These musicians are working HARD,” he comments, “you can’t ignore sold out tours and the energy inside clubs when a grime track plays.” Truly, with the recent success of Skepta’s Mercury prize (beating the likes of David Bowie and Radiohead) you cannot dispute the work ethos of grime’s pioneers.

As grime develops beyond its humble beginnings it’s good to see it gaining the recognition it deserves, particularly as it stays true to its self-made roots (see JME’s Twitter bio for affirmation). It is, however, necessary to adopt a critical eye when discussing the means through which grime has achieved this, because often, the term “recognition” is synonymous with white approval.

![G.B. ENGLAND. [City/town. Sample caption. Year.]](https://gal-dem.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/SimonWheatley_1.jpg)