gal-dem in conversation with Sharmaine Lovegrove: the woman disrupting UK publishing

Zahra Hankir

09 Dec 2017

I meet Sharmaine Lovegrove at the London offices of Little, Brown Book on a crisp November morning. En route, I’m flustered and nervous—predictable symptoms of a Woman-of-Colour-crush.

The anxiety dissipates as soon as I arrive. Sharmaine is relaxed, radiating the subtle aura of fierceness that only hidden figures carry. Seated on a large couch in front of novel-filled shelves, she’s poised as the Nefertiti of the entire publishing industry.

Sharmaine, 36, has been the head of Dialogue Books, a new diversity-focused imprint, for five months. Though it’s not written in her job description, she’s tasked with disrupting an overwhelmingly white industry.

“The idea that people of colour aren’t included in the art of storytelling in this country when we’ve done so much culturally is outrageous,” she says. “How has that happened, when we’re from cultures that have survived and thrived on storytelling?”

“We’ve failed to include creative and dynamic people who have smarts in lots of different ways”

Sharmaine is chipping away at what she calls an “unconscious” bias, one book at a time. Her inclusive imprint specialises in writing by people of BME backgrounds, in addition to the LGBT+ community and those with disabilities.

“We’ve failed to include creative and dynamic people who have smarts in lots of different ways,” Sharmaine, whose proud roots are Jamaican, says of the industry as a whole. “A lot of those people come from diverse backgrounds. That kind of multitude of cultures is a bonus.”

Aptly named, Dialogue Books is set to fill a gap in the novels we find on the shelves of Waterstones and Foyles.

The stats are bewildering. Of the thousands of novels published in the UK last year, less than 100 were authored by non-white British writers (one of those authors was Kazuo Ishiguro, winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature).

At the same time, the success of The Good Immigrant,the now-ubiquitous anthology by immigrants in the UK, illustrates the demand for BME writing. “UK publishing is super cosy”, Sharmaine says.

“I’d say I’m challenging the status quo of what good books are”

When I ask Sharmaine if she’s on a mission, she takes a moment. “I’d say I’m challenging the status quo of what good books are,” she tells me. “I’m on a specific journey.”

Sharmaine left the post of literary editor at Elle Magazine to join Little, Brown— a division of publishing powerhouse, Hachette—in July. She hadn’t sought the role out, just as she hadn’t sought out her position at Elle. You might say they were crafted for her, and they sought her out.

“I’ve never been intimidated,” she says. “This idea that I’m not welcome into spaces in my own city that my family has been in for generations is unthinkable to me.”

Sharmaine’s first literary love was Roald Dahl’s Boy, which was handed to her in a brown paper bag by a bookseller at a Battersea bookshop when she was eight. “If I could make people this happy,” she thought, “my world would be made.”

In the decades that followed, books would become Sharmaine’s life. Still, she couldn’t break into publishing the way others had. Despite her experience, she received knock-backs when applying for in-house roles, unable to pinpoint why. Was it because she was black?

“They didn’t understand that someone who hadn’t studied English Literature could work in these roles,” she said (Sharmaine has degrees in Political Economy and Anthropology). “They didn’t know what to do with this energy.”

Sharmaine took that energy and continued doing her own thing, eventually opening a bookshop in Berlin — Dialogue Books. (Sharmaine is obsessed with the word dialogue, as “books are meant to spark conversation.”)

That entrepreneurial experience paved the way for others to approach Sharmaine to offer her opportunities, not vice versa.

Sharmaine wasn’t afraid to broach controversial ideas to the gatekeepers of publishing. In 2016, she was invited to a trends dinner with 20 key influencers at a Mayfair restaurant. On the topic list? Beyoncé’s ‘Lemonade’. The video, deemed by many as woke, was, however, subject to the sort of scrutiny that’s tinged with racial bias.

Sharmaine realised there was only one other WoC present, and felt uncomfortable with a predominantly white crowd critiquing something “they may not fully understand”.

“The nuance of every textured layer of Lemonade is so profound, so enlightened, so historically accurate, that unless you really know your Black History, you wouldn’t understand it.”

The only white man in the room questioned Sharmaine’s reluctance to delve into Lemonade’s place in pop culture. When she checked the individual, he name-dropped Kendrick Lamar, noting the importance of black political lyrics. “I’d literally been mansplained race by a white man,” she says.

As the evening progressed, Elle editors asked Sharmaine if she reads the magazine. She said no. Their response? To bring Sharmaine in to shake things up (while at Elle, she wrote pieces including “‘Books to Read if You’re an Activist.’”)

“I don’t want someone who’s white writing about the slave trade from the perspective of the slave”

The dinner discussion brings us to the much-debated idea of cultural appropriation in literature. Is it ever okay, I ask, for a white author to write a black character? Lines need to be drawn, Sharmaine says. “When something cataclysmic has happened within humanity, those voices should be left to people who were part of the legacy and their ancestors.”

“I don’t want someone who’s white writing about the slave trade from the perspective of the slave.”

Now seems like the ideal moment to ask Sharmaine if she has a role model. “I’m too committed to storytelling to not recognise that we’re all flawed,” she says. “I look at so many women and think power to you, keep being awesome. But I never put anyone on a pedestal. I take a story for what it is. And I respect it.”

Still, I manage to pull some names out of her: Toni Morrison, Maya Angelou, Margaret Busby, Elise Dillsworth, Ellah Wakatama Alfrey, and Sonia Meggie.

“Of course I love Beyoncé,” she says when I coax her. “But I also love the women at my local flower shop,” and hidden women, like her aunts.

“Sometimes we don’t allow our art to speak for itself”

On that note, Sharmaine says her imprint will focus on ‘hidden’ stories. “The books are an engagement of othered and marginalised people. It’s about bringing them into the dialogue.”

Sharmaine comes from a family of activists — her uncle, Len Garrison, was the founder of the Black Cultural Archives. Her advice to aspiring writers of colour is to “use your anger and activism to tell the story and to let your characters speak the narrative.”

“Sometimes we don’t allow our art to speak for itself,” she adds. When presenting your work, be open to feedback and “don’t let anyone tell you there’s no audience. Make them tell you about your writing.”

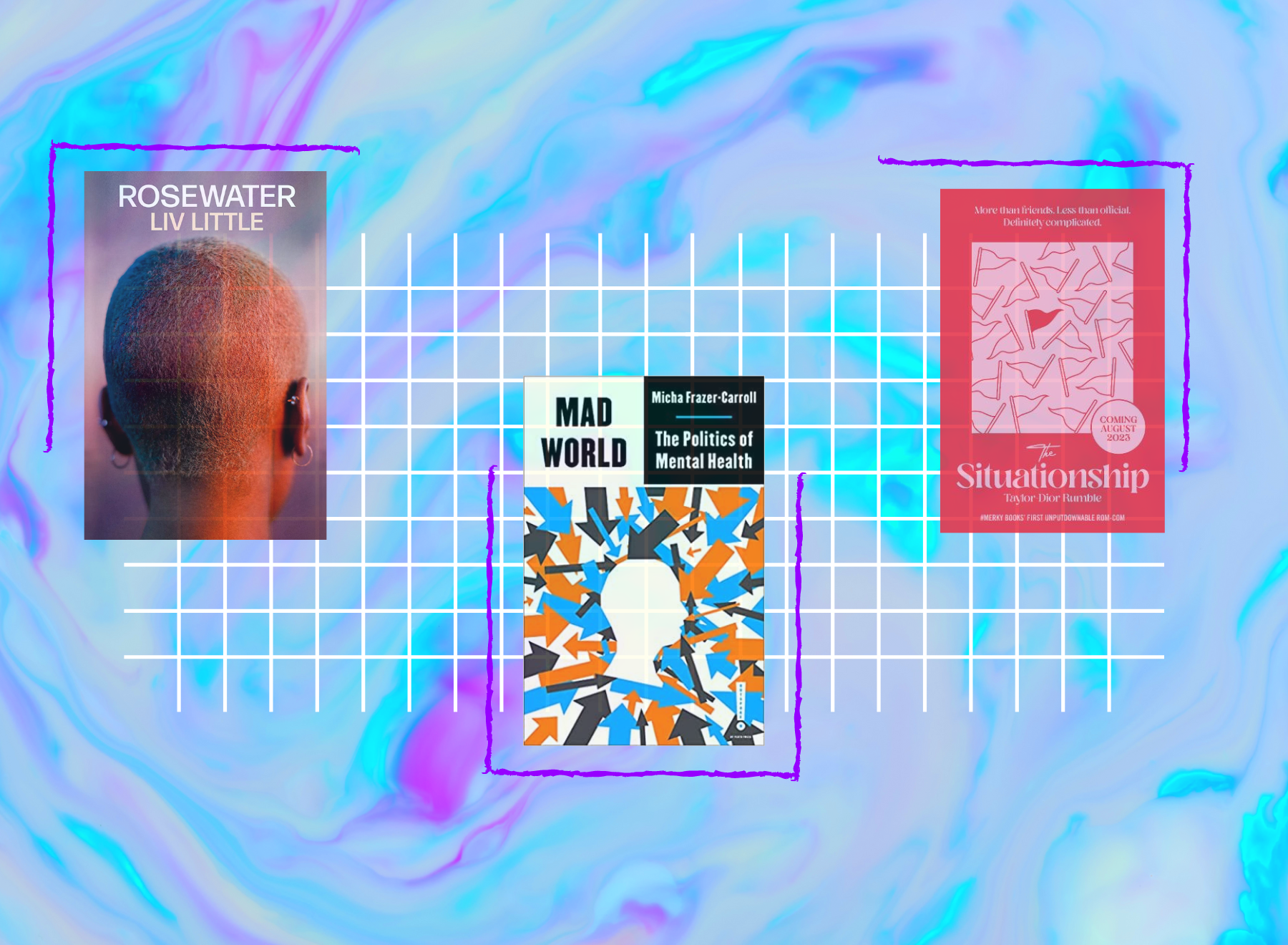

Sharmaine has already commissioned over ten books, among them, the US edition of “The Good Immigrant”. Their scope is wide-ranging, dealing with class, addiction, assimilation, slavery, and eroticism.

“Black, List,” by Jeffrey Boakye, stands out. It features over 60 contentious words used to describe black men and women—several touch on black masculinity.

A black man, explaining race. If that won’t spark the sort of dialogue Sharmaine wants people in this country to have, I don’t know what will.

*

One book she’d have loved to publish: Maya Angelou’s “And Still I Rise”

Recommended WoC authors: Bernardine Evaristo, Diana Evans, Irenosen Okojie

(Some of her) favourite authors: James Baldwin, John Berger, Tahar Ben Jalloun, Roald Dahl, Judy Blume, Maya Angelou

Favourite recent books: “The End We Start From” (Megan Hunter); “Flesh and Bone and Water” (Luiza Sauma); “Speak Gigantular” (Irenosen Okojie)

Film she’d turn into a book: I’m Not a Witch

Playing on her iPhone: “‘Everybody Loves the Sunshine’” (Roy Ayers).