BBC / Lovers Rock

Queer Lovers Rock: the reality of nightlife for gay Black women in 80s & 90s London

After seeing *that* kiss in Steve McQueen’s Lovers Rock, we wanted to know the realities of London nightlife for gay Black women at the time.

Elete N-F

14 Mar 2021

For many of us, what stood out in Steve McQueen’s Lovers Rock – in addition to the amount of times ‘Silly Games’ was sung – was that snippet of a scene in which two girls share a kiss in an upstairs bedroom. The context, or lack thereof, was curious: did they know each other? Will this happen again for them? It half doesn’t matter, because that is what parties are about: there isn’t a backstory behind every kiss shared at parties in real life, so there shouldn’t be one just because it’s two Black women.

Blues parties, such as the night shown in Lovers Rock, took place in Black people’s homes from the 1970s. They were a space for the communal enjoyment of sweet, slow Lovers Rock music, home-cooked food, and company away from racist nightlife around the city. These girls’ very brief appearance in the film begs the question: where would you go and see many pairs of women like this one?

I spoke to DJ and sound artist Ain Bailey and poet Dorothea Smartt about their experiences of Black queer nightlife in the 80s and 90s. We spoke about what it meant to spend those nights with friends, strangers and community.

“You’d have a gay following and a straight following. And everybody would just be there”

Although both were clear in emphasising that it wasn’t all a bed of roses, I wanted to know what they made of the idea of two girls sharing a secret kiss upstairs at a house party like in Lovers Rock. Dorothea suggests that a queer couple might have been at a blues house party for the music, and they may have gone upstairs to have some privacy. But not necessarily to hide away – anyone who was at a more “straight” party was there to hear a particular DJ. So “you’d have a gay following and a straight following. And everybody would just be there.” In general, though, she notes that the reggae and Lovers Rock scenes were more overtly heterosexual, which lines up with Ain saying that she hasn’t been to a straight blues party since coming out.

What rang true for Ain from Lovers Rock was the setting: most queer, Black gatherings were at house parties until queer spaces started to appear, notably the now closed Kennington lesbian bar Southopia. When it then came to choosing between destinations, it was the music that led the decision. Dorothea, too, emphasises how much music overwrote any escapades and journey lengths; she was always one of the last people standing on the dancefloor and when the lights were up you’d go home – continuing the party if you were so inclined – on the night bus.

As Ain impressively lists some of her favourite haunts, it becomes clear that, rather than there being one queer party that everyone had to like or lump, there were many places that everyone went to depending on what they wanted to hear, and who they wanted to see.

“So a friend and I did a night called Precious Brown. We launched that in 97. And I think going backwards there would have been… so the Candy Bar opened like 96, 97,” Ain tells me. “There would have been Low Rider, which was run by queers but open to everyone. There was obviously Queer Nation, which is probably one of the bigger clubs, along with Lowdown, Market Tavern, which had a Black gay night, Eve’s Revenge at the Fridge in Brixton, Sauda, which was like a performance night specifically for Black women, as well as Shugs at the Brixtonian,” Ain says,

“Most queer, Black gatherings were at house parties until queer spaces started to appear”

As well as music, who they saw on the dancefloor differentiated one space from another. Ain luckily had a route into queer nightlife once she came out, though it was predominantly with white people she knew from work. When it came to entering the scene where other Black LGBTQI+ people were, she notes a weekly group in Holborn and her family’s community centre in Brixton as leading her towards them.

Dorothea similarly had to seek out other queer Black women to party with, because she spent most of her time with two friends who were queer men of colour at clubs mostly populated by other queer men. But that was not for her trying to find other queer Black women’s haunts.

Dorothea would often call up Switchboard, the helpline formerly known as London Gay Switchboard, to try and get a hold of the one Black woman who worked there and find out whether she could suggest anywhere to go out. As they couldn’t disclose staff members’ working hours, though, Dorothea would often end up speaking to a “nice white guy” who would, after hearing her request, agree that she’d need to speak to the person she was after. She never did get through to her – Dorothea reassures me that she wasn’t calling endlessly, just once in a while to try her luck.

One thing that stuck out as a constant in queer nightlife then and now was the direct line between parties and the space made for community projects, performances and care. For Ain, parties were for just that – enjoying music, seeing people, and dancing. But alongside that, she edited the magazine wickers & bullers, a self-described “almost serious Black lesbian and gay publication” for the community. It was projects like this that provided the kinship that wickers & bullers documented; they put on some club nights as a publication, too.

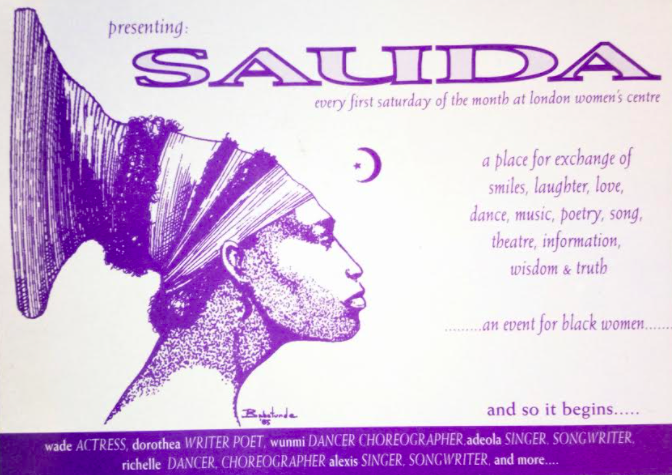

Dorothea remembers how welcome a space this magazine created, even just through its name (“wicker” and “buller” are Caribbean terms for queer women and men, respectively) and recently shared the magazine with a friend in Barbados who suggested a 2021 recreation of the group photo on the cover. Another name that came up as a significant date in the calendar was Sauda: a monthly evening for Black women (which Ain says made for some interesting conversations at the door) that took place at the London Women’s Centre.

“I got there and [it was] a Black lesbian party. And I was like, ‘what? Why didn’t you just say!’”

In the posters that Dorothea showed me, Sauda offers “a place for the exchange of smiles, laughter, love, … wisdom & truth,” with singers, dancers, actresses, poets and more on the bill. Dorothea was one of these performers, and more doors opened up as a result of her attending festivals. The happy ending to the unfruitful calls to the Switchboard is that after attending a festival in Amsterdam, of all places, Dorothea found her way into queer Black women’s parties.

“I got the bus, and there was this other Black woman on the coach, she was quite shy. And eventually, we got speaking and exchanged information. She said something about, maybe I’d like to come to some women’s parties or something in London. And I thought… hen parties, you know?”

On Dorothea’s return to London, the two stayed in touch, and she often invited her to a Black women’s party in Peckham. “She asked me more than once I remember because it got to a point where I felt like I was being rude saying no, so I thought, let me go and see what this is about”, she says. “I got there and [it was] a Black lesbian party. And I was like, ‘what? Why didn’t you just say!’”

Ain and Dorothea paint a luminous picture of the Black queer nightlife of the 80s and 90s. While it doesn’t match the inconspicuous nature implied in the scene of Lovers Rock, the cornerstones of music, community and looking good are clear parallels between the nights they enjoyed and the party that McQueen showed. So if they were to make their own pieces in any form documenting this time, what would the main messages be? For Ain, it would be the wallpaper at the blues parties, food and music. For Dorothea, it would be music and a sense of acceptance.

Although this was a “what if” question, cultural pieces like these would be touchstones to mark the thousand words that a single image, story or sound recalls. It makes me think of photos, tickets and ephemera I have that stir up a snapshot of my friends dancing, the song we were dancing to, and the epiphanies of the smoking area. Conversations, anecdotes and pieces like these from Ain and Dorothea, as well as the 2021 wickers & bullers photo that Dorothea’s friend suggested, are vital for drawing out parallels not only between the various Black spaces that existed at one time, but elucidating how Black queer communities will always gather in the same way at the end of the day – or night.

Against the binary: finding home in my intergenerational queer family

The first time I owned my queerness was in front of an aunty doctor

‘The day Ghana’s anti-LGBTQI+ bill is passed, I will be in jail’