Read ‘Deporting Black Britons’ to understand the violence of Britain’s borders

Though the so-called Windrush scandal has been widely covered, the narratives of what happens to black Britons after they are deported are underreported. Through four intimate portraits, this book hopes to change that.

Leah Cowan

26 Oct 2020

Luke de Noronha’s new book Deporting Black Britons: Portraits of deportation to Jamaica provides an urgent, sensitive account of the impact of border violence and the ruptures which emerge due to Britain’s deportation practices.

His research couldn’t be more timely: in 2018, the UK’s sinister deportation regime hit the headlines as it emerged that the Conservative government led by Theresa May had been targeting members of the Windrush generation. The “lessons learned” review of the so-called Windrush scandal was published in March this year and included a requirement to diversify the Home Office. However, migrant’s rights charities and NGOs made it clear that “justice for the Windrush Generation will not be fully served until the Hostile Environment is scrapped and the attitudes which drove its creation are rooted out”.

The Windrush scandal – which exposed the underhand practice of deporting British Caribbean elders who couldn’t easily prove their right to reside (and were thus described by the Home Office as “low-hanging fruit”) – was part of the government’s attempts to meet net migration targets. The targets were vehemently denied by then Home Secretary Amber Rudd until she was caught in a lie and forced to resign.

What made the scandal particularly noteworthy is that the Windrush generation came to the UK as citizens. They found themselves subject to border enforcement as Conservative immigration policies slid violently to the right over the course of two consecutive immigration acts. This incident (actually part of a long trajectory of racist border enforcement) revealed very plainly the slipperiness of borders – how, as people of colour, for as long as borders remain our ability to “belong“ will always hang in the balance.

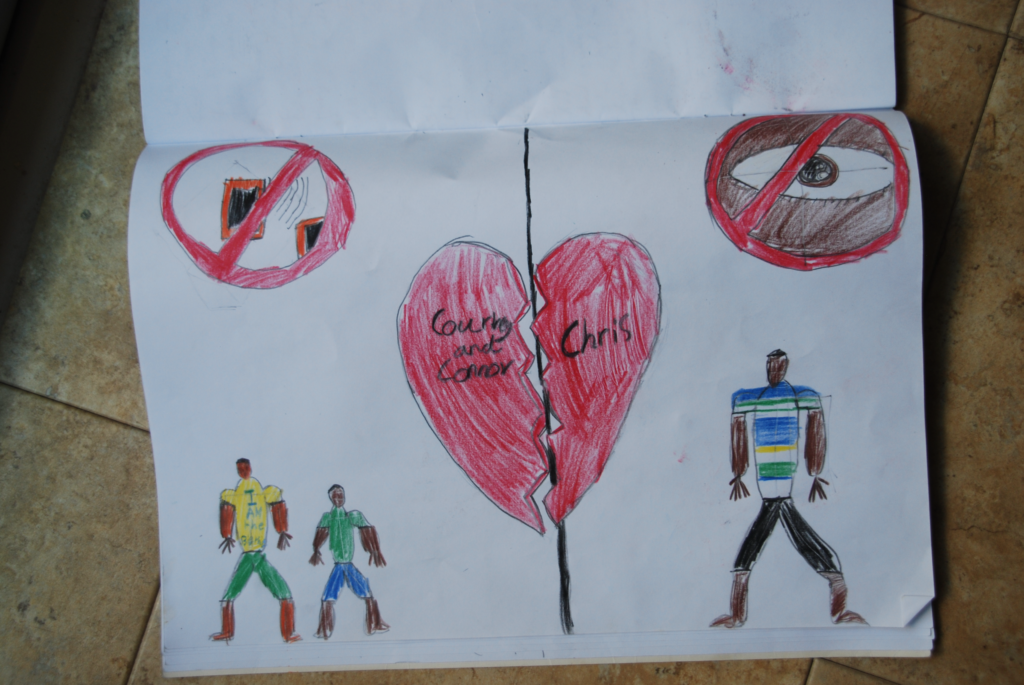

Deporting Black Britons explores this very paradox. Through intimate portraits, we learn about four young men – Jason, Ricardo, Chris and Denico – raised in the UK, who have been torn away from their friends, partners, children and communities and deported to Jamaica.

“The choice of using portraits was a political one about giving people space to be complicated, and making the people I met recognisable”

gal-dem: Why did you decide to write the book and research deportations to Jamaica?

Luke de Noronha: In 2006 the character and population of people in immigration detention changed. It went from being primarily asylum seekers to including a big proportion of “foreign national offenders” who’d grown up in the UK, had British accents and were indistinguishable from black and brown British citizens. I was interested in those kinds of stories. Jamaica was chosen partly because I got in touch with an NGO there who supports deported people [the National Organisation of Deported Migrants or NODM] and they agreed to host me, and partly because Jamaica is smallish and English-speaking. The journey of writing the book was focused on the most violent end of borders, the problematic, “difficult to defend” group of people with criminal records, people who had grown up in the UK. Jamaica became a good place, a practical place for me to live and meet people in that situation.

British involvement in forcibly moving people to the Caribbean has been a long-running practice. As you were researching, did you think about the relevance of colonialism to the process of deportation?

Definitely. That’s both something I thought about from the beginning, and something that I learnt more about as the research went on. One of the things that was most striking in Jamaica was the historical imagination and commonsense of ordinary people when it comes to thinking about the histories of colonialism and slavery. In Britain, the commonsense around imperialism is either complete ignorance or nostalgia and celebration. Whereas in Jamaica it struck me straight away that the history of enslavement followed by neo-colonial development and debt are the very reasons why people would move and leave Jamaica. They are also the reasons why, when they get to other countries, they might face certain forms of racism – a legal exclusion that leads them to become involved in criminal modes of income generation. Then, when people are deported, they return to the kind of ghettos and poor areas of urban Jamaica where life is pretty difficult, especially if you don’t have any social support.

Your book presents four portraits of men deported from the UK to Jamaica. Why did you choose to use the intimate method of portraiture to tell this very broad-reaching story about border violence?

I was really interested in doing something like ethnography (as someone doing an anthropology PhD), and less interested in having an NGO help me to pencil in loads of one-off interviews. I wanted to get to know people, and that was necessary for trust as well. The best description I can come up with is a quote that says “ethnography is a kind of deep hanging out”. I wanted to do that deep hanging out because I thought, that’s what people deserve when they’ve been through deportation, and I’m interested in complex human stories, not in extracting themes.

The four guys in the book were people I got to meet within the first few weeks and were people who opened up, who seemed to get along with me and think I was alright. It wasn’t that kind of ethnography which is traditional in anthropology where you go to a street corner or join a social movement, or you follow the police around, or you go to a specific pub…it was life stories. There are a few ethnographies, particularly in Caribbean anthropological work, which are life stories of one person, and I really like them. I think that they are a beautiful way of working through issues and the fullness of a life and that they take people as a whole complicated person really seriously, rather than as a vehicle to make a more theoretical argument. The choice of using portraits was a political one about giving people space to be complicated, and making the people I met recognisable.

“A lot of the arguments around the specific victimhood of particular groups of people tend to reinforce that borders are a force for good”

It sounds like you wanted to be able to hand the guys that you were hanging out with a chapter, so inevitably you’re writing it for them, but were there other specific people in mind?

Writing it for them was important. Les Back [a professor of sociology at Goldsmiths University] has this bit in The Art of Listening, where he says something like, “I try and write by imagining that the people I’m writing about are over my shoulder”. That doesn’t mean that he writes so that they really like it – because you will have read the Chris chapter and you can see there that there’s a kind of reckoning with the fact that he said some misogynistic things which I found difficult. For me it isn’t about saying, “I’m going to make you come out as well as possible”, it’s about knowing I could look someone in the eye and talk about what I’ve written about them.

I also want the book to help improve the way that academics, anti-racists, activists think about some key questions, such as what kinds of arguments should we be making when we defend migrant rights? Who is excluded when we focus on deserving-ness, contribution, innocence, victimage?

Yeah, a kind of stratification emerges of who is the most deserving and who is the most in danger. How do we open up access to rights and justice, without galvanising the unequal systems we ultimately want to be destroying?

I think a lot of the arguments around the specific victimhood of particular groups of people tend to reinforce that borders are a force for good, and they distinguish between goodies and baddies, and victims and villains. I’ve been reading statements from the Yarl’s Wood hunger strikers from 2018 and they don’t use the language of “women” they use the language of “people”. This is partly because they recognise the detention of all people being wrong, and they also talk about trans people who have been denied their medication in detention. They make a range of arguments about people without relying on women’s victimhood in particular or on the gender binary.

We need to think about border abolition in terms of what steps you can conscionably and strategically take now. There might be reforms that aren’t going to dismantle borders tomorrow but don’t make things worse, and don’t expand the power of the state. We can build the way for future gains.

Deporting Black Britons: Portraits of deportation to Jamaica is out now with Manchester University Press. This interview has been edited for length and clarity

Britain’s policing was built on racism. Abolition is unavoidable

How Pakistan’s Khwaja Sira and transgender communities are fearing and fighting for their futures

Their anti-rape performance went viral globally. Now what?