No 10 Downing Street/Canva

Ready for Rishi? We’re not and never will be

Failing to address the cost of living crisis was just a part of Rishi Sunak’s terrible past record. Here’s everything bad the Tory politician has done.

Kimi Chaddah

03 May 2022

This article was updated on 2 November to reflect Rishi Sunak’s new role as Prime Minister.

Rishi Sunak’s ascent to Prime Minister has been praised as a ‘win’ for race relations. But it’s a particularly narrow view of winning – and of race relations as a whole – to frame his ascent as a win on the basis of representation alone.

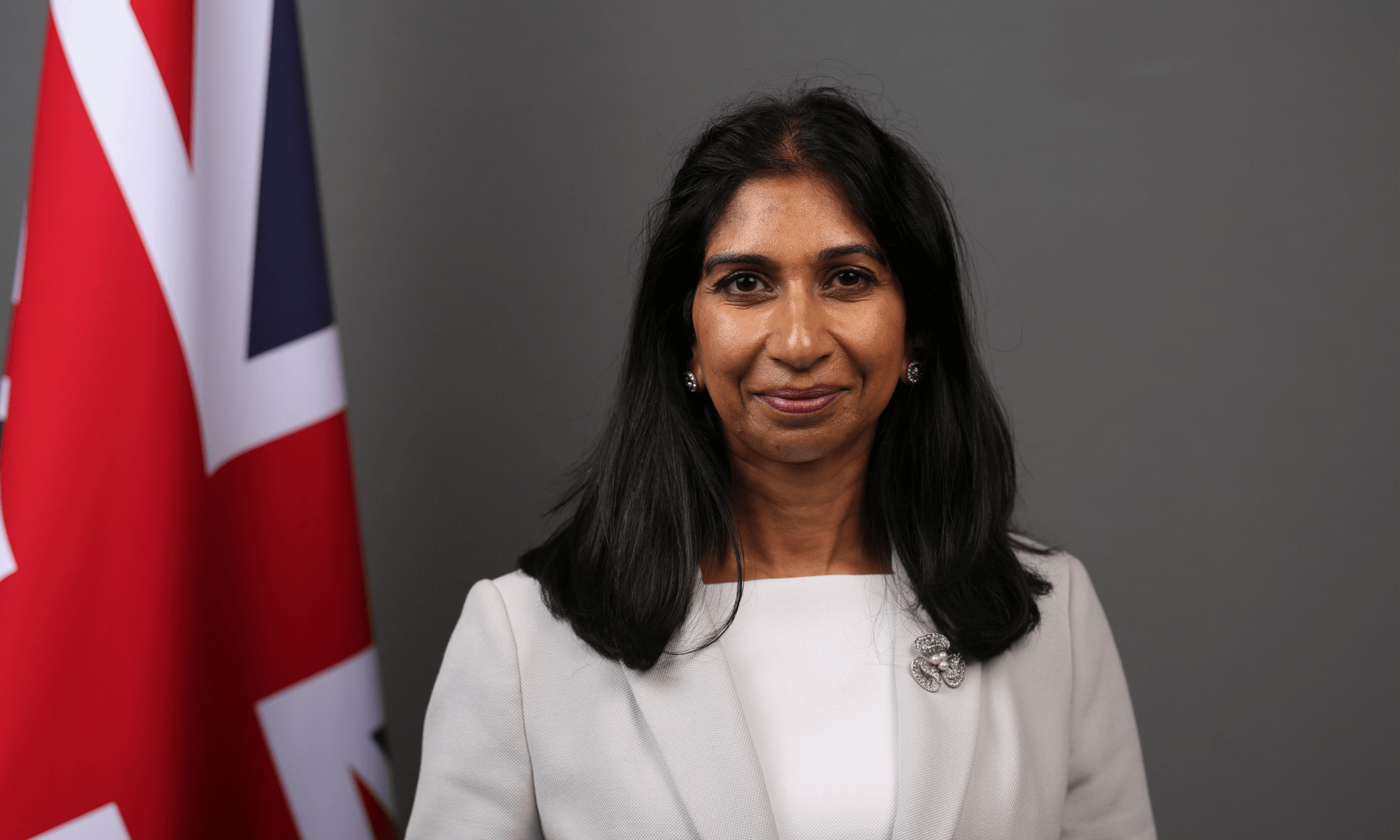

So far, Sunak has been complicit in the ongoing crisis occurring in immigration centres. Conditions of overcrowding and disease are rife, and in appointing Suella Braverman as Home Secretary a mere six days after she resigned, Sunak’s win has ensured a continuation of the same legacy of suffering for marginalised communities. And when this was pointed out last week by Labour MP Nadia Whittome, who posted a tweet describing how Sunak “isn’t a win for representation”, she was swiftly instructed to delete it by the Labour party.

Sunak’s rise to the top has largely been clouded by a lack of sense. The latest leadership election, which was framed as a battle for the supposed “soul” of the Conservative party, has bolstered Sunak’s image as the answer to Britain’s problems. This is a long-term project propped up by ambition, self-preservation and swathes of encouragement from the right-leaning media. Sunak has long been portrayed as saviour-in-chief: the Times of London adorned him with a halo in August 2020, the BBC characterised him as Superman and British tabloid the Sun labelled him “Dr Feelgood”.

But holding Sunak up as the epitome of representation ignores both the glaring lack of diversity – in terms of gender and class – in his Cabinet, and his sheer personal wealth. Sunak is thought to be the richest member of Parliament – and wealthiest prime minister in 127 years, at a time when the country is in a political and economic crisis. His wife, Akshata Murty, willingly claimed non-domicile status, enabling the avoidance of paying UK tax on foreign earnings up until April, after a political row. With the cost of living at an unaffordable level, Sunak suffers from the insulated worldview prevalent in Westminster and an inability to comprehend the lives of those on the poverty line. Earlier this year, he insisted that he could not solve “every problem”, hastily replying with “we can’t do everything” during a BBC interview.

Now, a man who previously absolved himself of responsibility – like Boris Johnson, disappearing at any sign of a challenge – is now guiding the country through one of the greatest crises since the Second World War. Go beyond the Westminster bubble and the unfolding social and economic crisis is laid bare – it’s how Sunak responds to these challenges, and not empty symbolism, that will dictate how he fares.

Pandemic response

- In August 2020, Sunak was the mastermind behind Eat Out to Help Out – a policy so popular he adorned Number 11 with its sticker. But it was also a policy that contributed to between 8% and 17% of new Covid-19 infections that month, according to researchers at the University of Warwick.

- While we’re on the topic, catch-up funding for schools over this academic year was little more than one month allocated for the Eat Out to Help Out scheme.

- The UK’s Statutory Sick Pay, which doesn’t cover the value of the real living wage (£346 per week), is one of the least generous in Europe and in 2020 was found to breach EU law. As rates of Covid-19 surged, low sick pay forced people to choose between self-isolating and putting food on the table. Despite this, Sunak staunchly refused to increase sick pay for Britons.

- Sunak has overseen the largest amount of fraud of any Chancellor – nearly £9bn of PPE and £4.3bn in Covid-19 fraud have been written off. Yet the Conservatives still curiously maintain that there is no “magic money tree”.

- In his 2022 Spring Statement, Sunak promised to provide support to those who need it, echoing his words at the start of the pandemic. But three million self-employed people have not received anything since the pandemic began and were excluded from the furlough scheme.

Economic policies

- Sunak has introduced more tax rises in two years than in Gordon Brown’s chancellorship over almost a decade – tax rises that are aimed at low- and middle-income families.

- There’s been no growth in funding for state schools, but Sunak’s donated more than £100,000 to his old public school. All hail the meritocracy…

- Sunak’s reaction to the energy crisis rendered him less of a Superman and more of a Chancellor reigned by Wonga. Let’s compare: in France, the government has limited energy bill hikes to 4%, forcing the state energy company to bear a £7bn loss in value to protect its citizens from rising costs. And in Norway, the parliament voted to extend its energy subsidy scheme, which allows the state to cover 80% of energy bills when prices rise above a certain level. In Britain meanwhile, despite households facing bill hikes of £600 this year, we have what is effectively a £200 loan (although Sunak has strongly defended his scheme).

- In March, Sunak announced he would cut fuel duty by 5p a litre to try and ease the burden of the cost-of-living crisis. And in an effort to further the impression of himself as an “ordinary guy”, Sunak decided to use a Kia Rio for a photo op. Except the car isn’t his – it’s owned by a Sainsbury’s employee. In reality, Sunak owns four cars, including a Range Rover based at one of his homes in Yorkshire.

- Sunak’s legacy is largely characterised by inaction: in 2021, he did not stop the £20-a-week cut to Universal Credit, the largest overnight cut to the basic rate of social security in Britain since the second world war. In December, instead of helping businesses in the hospitality industry, Sunak jetted off to California, where he also holds a green card despite being a serving official of another country.

- Speaking to Labour MP Angela Eagle in March, the multi-millionaire described how he was “comfortable” with the choices he’d made as Chancellor – choices that have meant plunging 1.3 million people into poverty in the midst of the biggest drop in household income on record, according to the Office for Budget Responsibility.

Voting record

- On the eve of the Spring Statement, ministers voted to give bankers a tax cut worth £1bn a year. And this isn’t an isolated incident: Sunak has consistently voted against higher taxes on banks, which comes as no surprise from a former banker.

- As any good Tory, Sunak has voted for a reduction in spending on welfare benefits (between 2015-2016), and against paying higher benefits over longer periods for those unable to work due to illness or disability.

- Sunak has generally voted against laws to promote equality and human rights, including voting in favour of repealing the Human Rights Act in 2016.

On the environment

- Between 2016 and 2020, Sunak largely voted against measures to tackle the climate crisis. He was against a vote to require a strategy for carbon capture and storage for the energy industry, and against a motion calling on the Government to launch a “green revolution”.

- In 2021, company filings revealed fossil fuel giants Shell and BP had failed to be taxed on North Sea oil and gas profits for three years. Meanwhile, in February, fellow fossil fuel company Exxon Mobil lauded its most profitable year in seven years, having received £360m worth of subsidies from the UK government.

The contribution of our members is crucial. Their support enables us to be proudly independent, challenge the whitewashed media landscape and most importantly, platform the work of marginalised communities. To continue this mission, we need to grow gal-dem to 6,000 members – and we can only do this with your support.

As a member you will enjoy exclusive access to our gal-dem Discord channel and Culture Club, live chats with our editors, skill shares, discounts, events, newsletters and more! Support our community and become a member today from as little as £4.99 a month.

Britain’s policing was built on racism. Abolition is unavoidable

How Pakistan’s Khwaja Sira and transgender communities are fearing and fighting for their futures

Their anti-rape performance went viral globally. Now what?