Ritual Blackness: creating space for the future of black queerness

Khaleb Brooks and Angela Dennis

25 Apr 2018

Visibility, inclusion and acceptance of black queerness is happening in this moment. Some are referring to it as a renaissance, some are afraid it won’t last long, others are rushing to capitalise on their identity – all of us are dumbfounded by our own beauty. There is a sense of gratitude in not only seeing queer blackness shine but being able to say: “You inspire me, I’m coming to your show”, and, “that’s my friend”. It is also a time of transnational exchange, we are connecting across the globe rapidly in a whirling movement fully aligned with assured transcendence. “I can do this”, and, “you can do this”, is now, “we are doing this”, and, “we have done it”.

Blackness itself encompasses a multitude of experiences, politics and cultural production globally. While its meaning has always varied depending on events and geographic location, we must recognise the transference of these meanings internationally. Blackness is movement. Blackness is change. Blackness is African, diasporic and continues to connect communities formerly worlds apart in affinity. While it has often been founded on marginalisation, it’s exclusion from Western modes of power offers a space to re-imagine oneself and community. In many ways, we are utilising the margins themselves, to achieve inner and communal progress. Being positioned as outsiders is only leading us to build our own homes. Let us not forget our foremothers and fathers, from Josephine Baker to Rotimi Fani-Kayode and from Claude McKay to Lorde and Baldwin; black queer transnational artistry in particular, is in our collective memory.

I had the privilege of meeting Llewelyn during my first week in Johannesburg. One late night, a friend of a friend was flabbergasted I hadn’t yet met my neighbours.

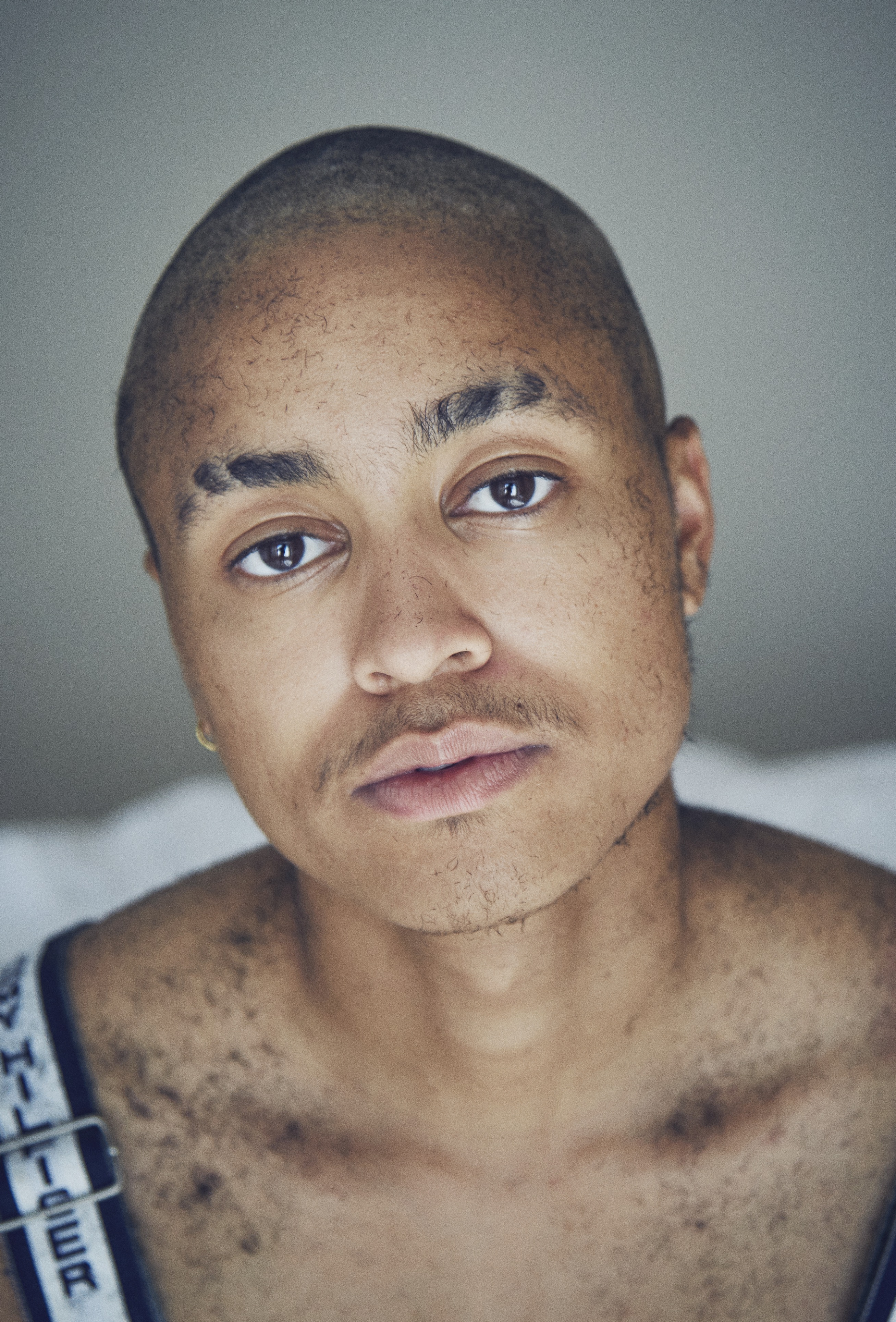

Llewelyn and Sia, black queer artists, performers and dancers lived in the same apartment complex as me. The SAME apartment complex! Excited, I rushed a few houses down, knocked on their door and found two kindreds. Within a few days Llew and I were sharing coming out stories, discussing black queerness and realised our birthdays were a day apart. Llew began training as a dancer at the age of 14 and teaches and performs globally. His work attempts to inspire the LGBTQ+ community and he is currently playing the character Odile in the production Swan Lake with the Dance Factory. “Adversity is never far,” he told me when discussing being brutally gay-bashed for the first time, “but this is why we do what we do, it really does make us stronger”.

“‘Adversity is never far,‘ Llewelyn told me when discussing being brutally gay-bashed for the first time, ‘but this is why we do what we do, it really does make us stronger’”

Before we knew it, we were staying up late watching FAKA music videos and his performances in collaboration with South African photographer, Zanele Muholi. At the time, I was doing an artist residency and researching how blackness as ritual translates to image making. I finally had the time to read, experiment and think about my creative process. Angela, a photographer and longtime friend from the QTIPOC scene, was also in town from London. She was covering AfroPunk and was greatly interested in exploring the black queer body in her work. Having felt her creativity inhibited by learning and working in predominantly white spaces, being in Jo’burg was an opportunity not to shy away from blackness, queerness, sexiness and love as themes in her photography. Between the epic bathtub in my residency space and a newly painted basketball court, we all decided it was time to continue our need to disrupt notions of beauty.

Llewelyn looked over at me with assurance as he turned on the clippers and the first clumps of hair fell to my shoulders. “Umm so how should I go about this?” he asked with a smirk, knowing he was in full control of my hair fate. “It’s all going!” I said, excited and nervous. I had never gone completely bald before. My hair throughout my life had always confirmed and affirmed the relationship between my blackness and masculinity.

Many AFAB masculine of centre people remember those moments when you first decide to go short. You tell yourself, alright, this is the real deal, suddenly I’m throwing myself in with a completely different crowd! Butch life, dyke life, trans life, here I come! But this moment was different. As of late, I had been discussing assumptions around my masculinity and trans identity. Due to presenting as masculine, those who don’t know me well presuppose my interests in undergoing gender reassignment surgery, as well as who I date and my personality traits. I began to question many of the boxes of femme and masc adopted into our LGBTQ+ world from mainstream society. Why can’t I wear a suit and be femme? Why are my actions covertly racialised within a frame of hyper black masculinity? Why don’t people ask?

“Why can’t I wear a suit and be femme? Why are my actions covertly racialised within a frame of hyper black masculinity? Why don’t people ask?”

I began considering rituals that would shift my material body from one of contestation to one of power. As hair is such a racialized and gendered part of the body, it offers a physical material to provoke. And in this case, this ritual would accentuate ambiguity. Slowly, as thick, brown, afro hair falls, a signifier of blackness is removed. Certain ways in which people respond to you instantly change. You find yourself moving, moving into an unknown place. There is your colour, your features, your energy, the way you walk, the tone of your voice. And my new dear friend took on this intimate act, allowing me to let a part of myself go. I began wondering, is it just a haircut or should we be pushed to think further about transcendental shapeshifting in our community?

According to scholar Agnes Horvath, during the alchemical process of identity transformation, matter both disintegrates and is created. When a metal undergoes an alchemical process, a literal death of the former identity of the object takes place. During death, there is suffering before a new identity is reached where a completely new existence in space occurs. It is a process where states of pain can be transcended while disrupting previous order and hierarchies. And for me, therein lies the ultimate power of queer black culture. We not only learn not to fear change but encourage it. It takes that mentality to imagine an existence completely different from anything we have ever known. We are not at a precipice but a return. We have reached new heights but within a new world of policing, technology and opportunity. As we constantly push ourselves to grow, leading the way – as we have always done, let us not forget our rituals. Those quiet moments when candles flicker, when tears are washed away, when we are in water, when we are embraced without anyone ever letting go, when we tell secrets, when we choose not to speak, when we dance, when we paint, when self-love is the only thing ever worth feeling.

Ritual Blackness is a collaboration between photographer Angela Dennis and artist and writer Khaleb Brooks, who authored this piece. Angela is a photographer and cultural producer based in London. Inspired by fashion, the body in movement, and black cultural aesthetics, her work ultimately aims to centre wellbeing and empowerment of the subject being photographed.