Sondra Perry’s new show is an overwhelming racial whirlwind investigating blackness and technology

Hélène Selam Rose Kleih

16 May 2018

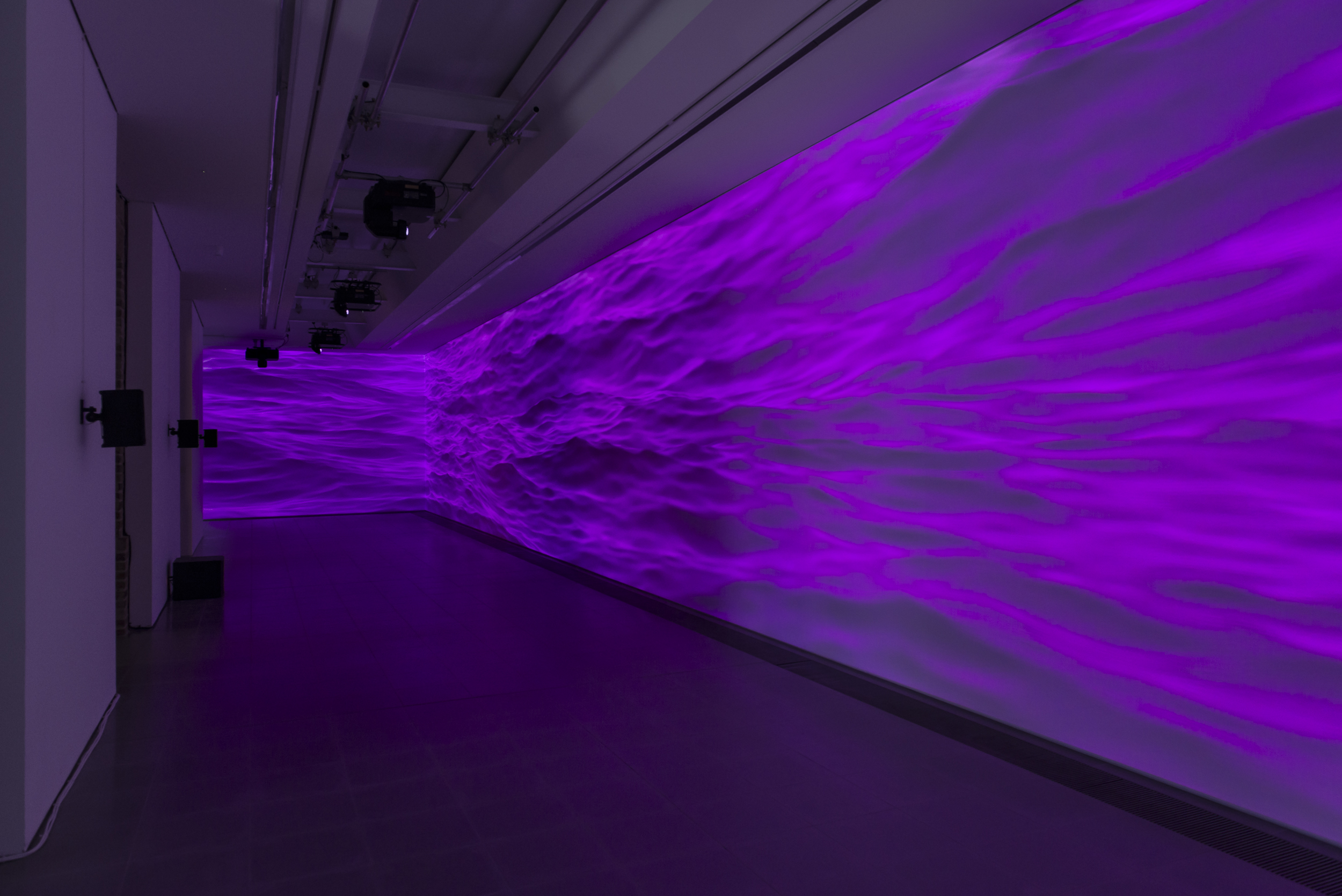

Sondra Perry does not ask for permission but invades our senses with a foreign fear. At the installation of her first solo presentation in Europe, violently overwhelming purple waves assault us. Just about virtually discernible on the walls of the Serpentine Gallery, where the exhibition is taking place, is the digitally manipulated image of J.M.W. Turner’s 1840 painting Slave Ship, depicting the drowning of 133 slaves by the captain of a British slave ship, in exchange for compensation of “lost goods”.

‘‘You think of the things that might have happened. It creates a tension in your body and soul. It makes you anxious. It will stay in my head for years to come,” she tells me. Testament to Perry’s preoccupation with abstraction – my mother, like other visitors, became an active participant, rather than a bystander of trauma. Walking through the empty space with Perry pre-installation, her concern with “disrupting” passive individualism was now realised.

The video lends its name to the exhibition, Typhoon coming on, Perry’s visual investigation into the power of digital technology in representing identity, and how and by whom it should be mobilised. Perry is not only preoccupied with her own narrative – that of a black female artist born and raised in America (New Jersey) – but rather the ways in which technology and identities have interwoven to form a multifaceted polysemy of blackness.

“In her work, slavery is not an atrocity better left in the past, a titbit of colonial history discussed only in terms of ‘remembrance’ Black bodies are still very much commodified, misused, misconstrued and surveyed”

In her work, slavery is not an atrocity better left in the past, a titbit of colonial history discussed only in terms of “remembrance”. Black bodies are still very much commodified, misused, misconstrued and surveyed – black bodies are still differentiated from basic rights in the US constitution and beyond, physical objects who “know that they are labourers but also are trying to gauge how to sustain their lives longer”.

Elsewhere, ‘Graft and Ash for a Three-Monitor Workstation’ is modelled after a bicycle workstation, whilst an avatar version of the artist lectures the viewer about capitalism. Alongside, ‘Wet and Wavy – Typhoon coming on for a Three-Monitor Workstation’ is a water-resistant rowing machine where three screens play the purple computer-generated waves to the soundtrack of a tinny version of Missy Elliott’s ‘Supa Dupa Fly’. These exercise machines both have obstructions – pedals that are on backwards, machines covered in Vaseline. They’re rigged, but as Perry says, she “likes to think they rig themselves”. Commenting on capitalist efficiency culture, Perry berates the “pull yourself up by your bootstraps” rhetoric laden on black bodies.

Working primarily in video, Perry’s work has always been concerned with the conflicting enigma of representation; “the video itself is an objectless object – it’s still physical but has the ability to be a lot of different things at the same time”. This characteristic of digital reproduction affects the way black bodies are interpreted – the imagining, or imaging of blackness throughout history – and Perry shows how it is now blackness that can harness technology to combat oppression and surveillance.

Perry uses Blender, an open-source “3-D rendering model making software” pertaining to a do-it-yourself generation – “as someone who figures out the technologies I need to use” – and her immersive large-scale projections use Chroma key blue screens (a post-production technique for compositing images based on colour hues). In a “space of post-production,” says the artist, “all of those problematics and possibilities are present. Chroma key blue and green are supposed to represent skin tone, but we ask whose skin tone?”

Moved by the problematics encountered with cinematographer and artist, Arthur Jafa’s film, Daughters of the Dust, (who showed at the Serpentine last year), where film stock could not capture “intense tones of dark skin alongside white garments”, Perry sought to dissect how black bodies specifically are being caught on film.

“So, I thought about the trend of warming up skin-tones to make them more palatable, I am interested in Kerry James Marshall’s work, the flattening and blackening – this is black, purple and blue – these cool tones. I was also thinking of the warmness of the fleshy organic surface and the symbolic warmth that you feel from a black presence. But, if I’m going to be warm, I’m going to be so contrasted, so hot that you’ll burn yourself if you decide you want to occupy me.”

The overall result is that Perry challenges “the way in which people want to encounter us – as a warm presence – something that is inviting.” In ‘TK (Suspicious Glorious Absence)’, the artist uses a Chroma key ‘Skin Wall’ (a close-up, modified image of her own skin) as a backdrop to a monitor that weaves footage from the 2015 Baltimore protests of Freddie Gray’s death, clips of “fake news”, alongside Eartha Kitt’s ‘I Want To Be Evil’, to reclaim the racist vulgarity and brutalisation inflicted on people of colour.

“She shows us that blackness is not about colour or prejudice but about circulation”

She shows us that blackness is not about colour or prejudice but about circulation. Referencing Fred Moten and the Undercommons, Perry compares the meme to blackness: “The meme circulates like blackness does – it is about space that people can move in and out of. But it’s predicated on its ability to move, to circulate – that’s how it exists as its radical self. Which is through multiple hands, sometimes problematically, but shifting and multiplying all of the time.”

Perry’s comment is simply: that life is an obstacle course that is especially challenging for black bodies to navigate. Perry educates on the irony of freedom for the black community in America, of the past and the present, in a way that does overwhelm but does not shock like Donald Glover’s revolutionary music video for ‘This Is America’. Yet, they both demonstrate how blackness is free to morph and represent itself through technology.

With the show finishing this month, Perry has created a platform for not just herself but fulfilled her hope for foregrounding “the revolutionary and radical acts that women do on a daily basis that go unacknowledged”, with accompanying events featuring Diamond Stingily, and Cauleen Smith at Peckhamplex.

Where she’s being shown important – it is not the V&A where we’ve seen the likes of our own platform gal-dem takeover, or the TATE, who have welcomed BBZ London, it’s the Serpentine. As with Jafa’s show, we cannot discount the impact that a solo show and its stark confrontation of race have on the run-of-the-mill South Kensington family.

Sondra Perry’s Typhoon coming on runs at London’s Serpentine Gallery until 20 May 2018