South Korea is the world’s cyber sex crime capital. Why?

Technological advances have exacerbated an existing patriarchal culture, with fatal consequences. Now South Korean women are calling for change.

Alia Waheed

19 Jul 2021

Diyora Shadijanova

CW: Mentions of sexual assault

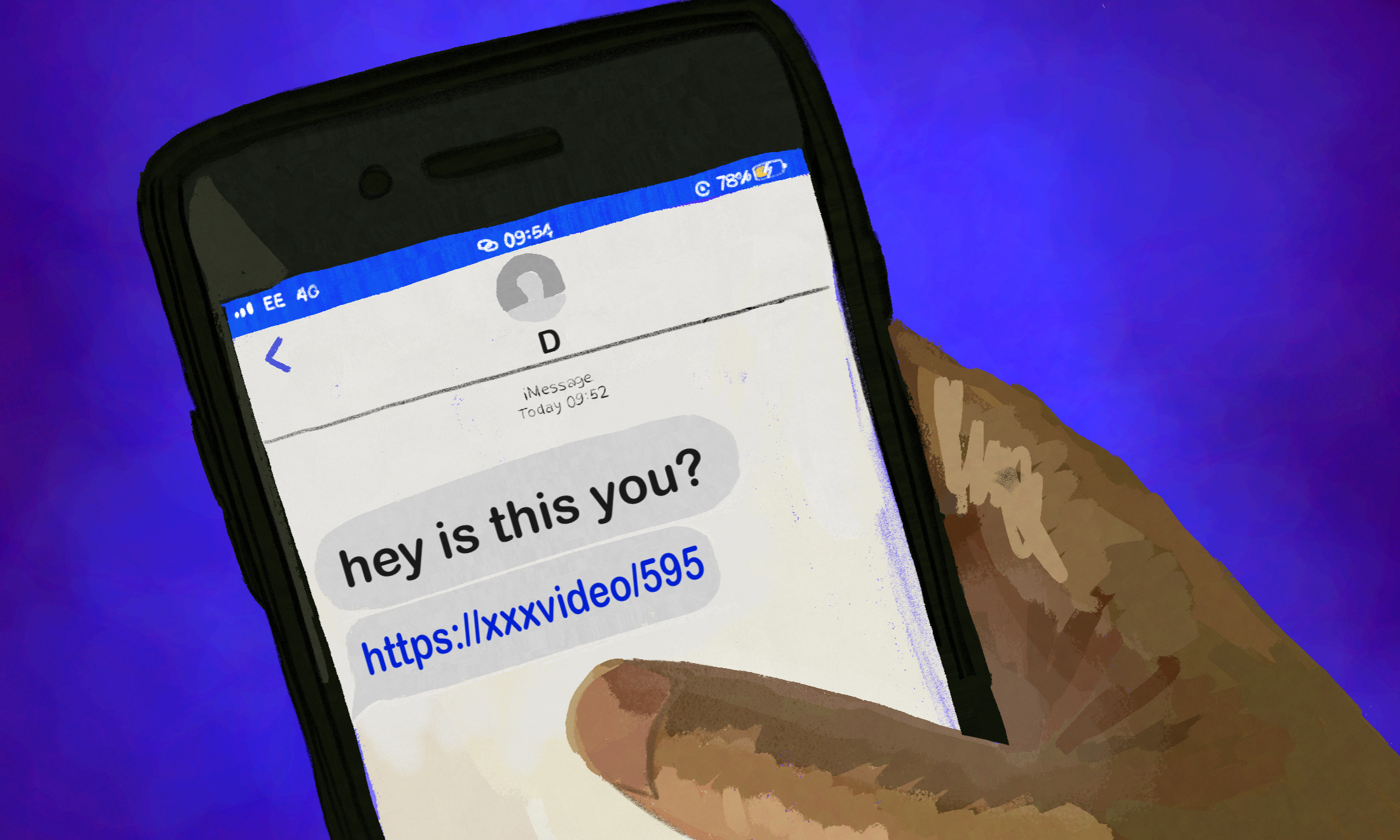

Like most tech savvy teens in South Korea, Seo-Yeon*, was glued to her smartphone in March 2020, when a message from a friend suddenly popped up. “Have you seen this?” the text read, followed by a string of shocked emojis.

Seo-Yeon clicked on the link and found a video of herself in a threesome with a caption underneath reading “Being raped makes me so wet.”

Except it wasn’t her and she had never met those men in her life.

She later discovered her ex-boyfriend had manipulated a sex video in revenge for her breaking up with him.

“When I clicked on the link, I was expecting a Tik Tok prank. I felt physically sick like I was watching myself being raped,” said Seo-Yeon, speaking on Zoom. The teenager now lives with her aunt in the USA and has since cut her hair and changed her name.

“I feel like my life was stolen from me,” she says, quietly. “I’m constantly looking over my shoulder and wondering if people I meet have seen that video. I was lucky my family could send me abroad. But I’m constantly on a knife edge. Now I’m too scared to go on any apps. I don’t even have Facebook. ”

When you think of South Korea, you probably think of its cultural exports like BTS and 12-step skin care routines. You might also reflect on its technological capabilities; the East Asian nation is one of the world’s most advanced countries for technology with the fastest and most accessible internet in the world.

Everyone in South Korea has a smartphone – 91% of the population own one, compared to 84% in the UK. The country also used to be a massive producer of the devices and millions of people around the world still own handsets made there.

But with all these advances comes a dark side – a huge rise in cyber sex crimes. Last month, a report released by Human Rights Watch (HRW) dubbed South Korea the “digital sex crimes capital of the world.”

“Often the perpetrators will also impersonate their victims online – either via hacking or setting up fake social media accounts – in order to destroy their reputation”

‘Digital’ or ‘cyber sex crimes’ refer to offences of a sexual nature that have a tech element involved. The term can mean anything from upskirting to filming rapes for online consumption or blackmail purposes.

Thanks to advances in tech, one of the most chilling developments of all are cases like Seo-Yeon’s, where women discover that they have had their faces digitally manipulated into sexual images or videos, a practice known colloquially as “deep fakes”.

Often the perpetrators will also impersonate their victims online – either via hacking or setting up fake social media accounts – in order to destroy their reputation and put them in danger of being sexually assaulted, which is known as sexual identity theft.

The statistics surrounding cyber sex crime make for harrowing reading: in 2008, 4% of sexual violence crimes in South Korea involved filming without consent. By 2017, the number of these cases had increased to 20%.

While South Korea may be one of the most technologically advanced countries in the world, socially it remains very much a patriarchal society.

The HRW report documented a culture where men often insist on marrying virgins and women can face ostracism and even lose their careers if they are considered promiscuous.

“South Korea is dealing with a toxic mixture of deep gender inequity and leading technological advances,” said Heather Barr from Human Rights Watch.

“Issues to do with sexuality are very sensitive in South Korea. If there are sexual images of a woman she may be blamed and face stigma from her family, friends and work.”

“Survivors know [investigations of cyber sex crimes] are not taken seriously so the retraumatisation hardly feels worth it”

However, evidence shows digital sex crimes are still not taken seriously and sharing videos among men is thought of as inconsequential. “What is now considered a crime and abuse was for so long part of entertainment culture,” Song Ranhee from Korea Women’s Hotline, told HRW.

“A lot of men feel the label of ‘crime’ for this is unfair. When someone is caught, they see him as unlucky, because it is so widespread — they know many others are not being caught.”

Hira Ali, author of Her Allies, A Practical Toolkit to Help Men Lead Through Advocacy, thinks this attitude trivialises online harassment. “It’s a form of gaslighting the victims by not recognising the impact it has on them,” she says. .

“Just because it’s normalised doesn’t make such occurrences acceptable. Not only do these women worry about protecting themselves, they also struggle with feelings of shame, disgust and confusion.”

Cyber sex crimes often have a devastating impact on victims like Kang Yu-jin*. After she broke up with her boyfriend of four years, she began receiving strange messages from random men. She immediately suspected her ex, but the police brushed off her concerns.

“When my ex heard I was dating again, he started posting dirty things while impersonating me [on social media], including fake nude images, photos of genitals and a couple having sex where the woman so closely resembled me that even my close friends thought it was me,” she explains.

Kang Yu-jin’s ex not only included her contact details, but the contact details of her parents and workplace, along with hashtags for her local neighbourhood, saying she was looking for multiple sexual partners and was interested in “rough sex”.

“Men tried to contact me at my parents’ church,” she remembers. “Some men came to my home and work for sex after seeing the address online.”

Kang Yu-jin was forced to quit her job and leave home. Although her ex was eventually convicted, he was only given a one year suspended sentence and community service. “This crime is the same as the social and mental killing of a person,” Kang Yu-jin says. As for the explicit images, it was left to her to beg social media companies to take them down.

Kang Yu-jin’s experience with the police and courts is far from uncommon. Often when women report digital sex crimes, they are brushed off or slut-shamed by officers who are predominantly male. The majority of cases are dropped before they reach the courtroom and even then, most perpetrators will face a fine of up to 10 million won (£6,800) or a suspended sentence. The maximum prison term given out is five years.

“Women often have very bad experiences reporting these crimes to police,” says Heather Barr from HRW. “Women described being mocked and interrogated for hours, sometimes in intrusive and inappropriate ways”.

“Women have told us the police collected intimate images as evidence, then passed the images around the police station and laughed at them. Survivors know [investigations of cyber sex crimes] are not taken seriously so the retraumatisation hardly feels worth it.”

“Sharing sexual images is a lucrative business with an hour of footage selling for between two to three million South Korean won (£1,200 to £1,809)”

But for victims, the fallout from cyber sex crimes can have fatal consequences. In 2019, South Korea’s failures to reckon with the issue were thrust into the spotlight after the death of pop star Goo Hara. Hara died by suicide following a brutal assault by her ex-boyfriend, Choi Jong Bum who then threatened to destroy her career by releasing a sex tape of the pair together.

After Hara’s death, Jong Bum was eventually sentenced to one year in prison by South Korea’s Supreme Court.

For those who carry on, the experiences weigh heavily. Other survivors told Human Rights Watch they had sworn off dating or sex altogether, or had undergone cosmetic surgery, such was their fear of being recognised. The growing “4B” movement (meaning “Four No’s” which are not to marry, date, have sex with or become pregnant by men) is attracting those who have experienced cyber sex crimes.

“I learned that in this country, if you are not male you cannot survive peacefully with your own sexual identity,” one 21 year-old survivor is quoted as saying in the HRW report.

“So, I chose – I will not have any relationship with men. I will not meet them. I will not marry them. I will not have any kind of relationship at all with a male.”

Revenge is just one motivation for cyber sex crimes. HRW found many perpetrators make substantial amounts of cash from circulating images of women in their most private moments on streaming sites and voyeur forums. Around 80% of digital sex crimes involve men using spy cams to secretly film women, known as molka.

Spy cams can be hidden in ordinary objects like clocks and even coffee cups, and have become so widespread that public toilets and changing rooms are considered no-go areas for women. Travel guides will even warn tourists to be on the lookout for spy cams.

“None of my friends use public toilets and changing rooms,” says Kelly, a British woman working in South Korea. “On my first day at work, I was warned it was rampant. My female colleagues all told me to be careful and inspect the toilet stall first.”

Sharing sexual images is a lucrative business, with an hour of footage selling for between two to three million South Korean won (£1,200 to £1,809). Images can be downloaded and shared globally within minutes, speeding up profits. There are even porn sites specialising in molka.

In 2019, the co-founder of South Korea’s largest porn site, Soranet, was sentenced to four years in prison for hosting thousands of illegal videos, many of which were filmed using spy cams without the victims’ knowledge.

“At the heart of the government response is a failure to appreciate how deep the impact of digital sex crimes is on survivors”

Although much of the footage is consumed domestically, there is also a huge Western market that fetishises South Korean women. Many people feel this is because of cultural stereotypes perpetuated by the candy sweet and sexualised imagery of the K-Pop industry. The “sex doll” stereotype of Korean women, with porcelain skin, big eyes and hyper-feminine style, has been challenged by young South Korean feminists, via movements like “Escape the Corset” in which women reject beauty standards by cutting their hair or throwing away cosmetics.

The spycam epidemic became the flash point for South Korea’s #MeToo movement and in 2018, thousands of women took part in protests across eight cities calling for a crackdown on spycam porn, carrying placards saying “My Life is Not Your Porn.”

While the authorities have attempted to tackle the issue, including sending armies of molka ‘Aunties’ (older women volunteers) to search public places for hidden cameras, often the law can’t keep up with the tech.

Critics feel solutions have been hit-and-miss, with a 2015 poster campaign on subway escalators (a hotspot for upskirting offences) featuring the slogan ‘Please Cover Your Skirt”, meeting widespread ridicule.

A Digital Sexual Crime Victim Support Center (DSCVSC), which was launched in 2018 to provide services such as counselling and legal support, has also been plagued with issues, after not receiving enough resources to keep up with demand.

“At the heart of the government response is a failure to appreciate how deep the impact of digital sex crimes is on survivors,” says Heather Barr. “The problems survivors face in the justice system are exacerbated by a lack of women police, prosecutors and judges. By changing the deep gender inequity that normalises consumption of non-consensual intimate images there needs to be a focus on prevention by teaching children—and adults—about healthy and consensual sexuality and responsible digital citizenship.”

However, many people believe that the law isn’t enough without social change. “Until we stigmatise the voyeurs instead of the victims, change can’t happen,” says Seo-Yeon.

*Names have been changed to protect identities

Britain’s policing was built on racism. Abolition is unavoidable

How Pakistan’s Khwaja Sira and transgender communities are fearing and fighting for their futures

Their anti-rape performance went viral globally. Now what?