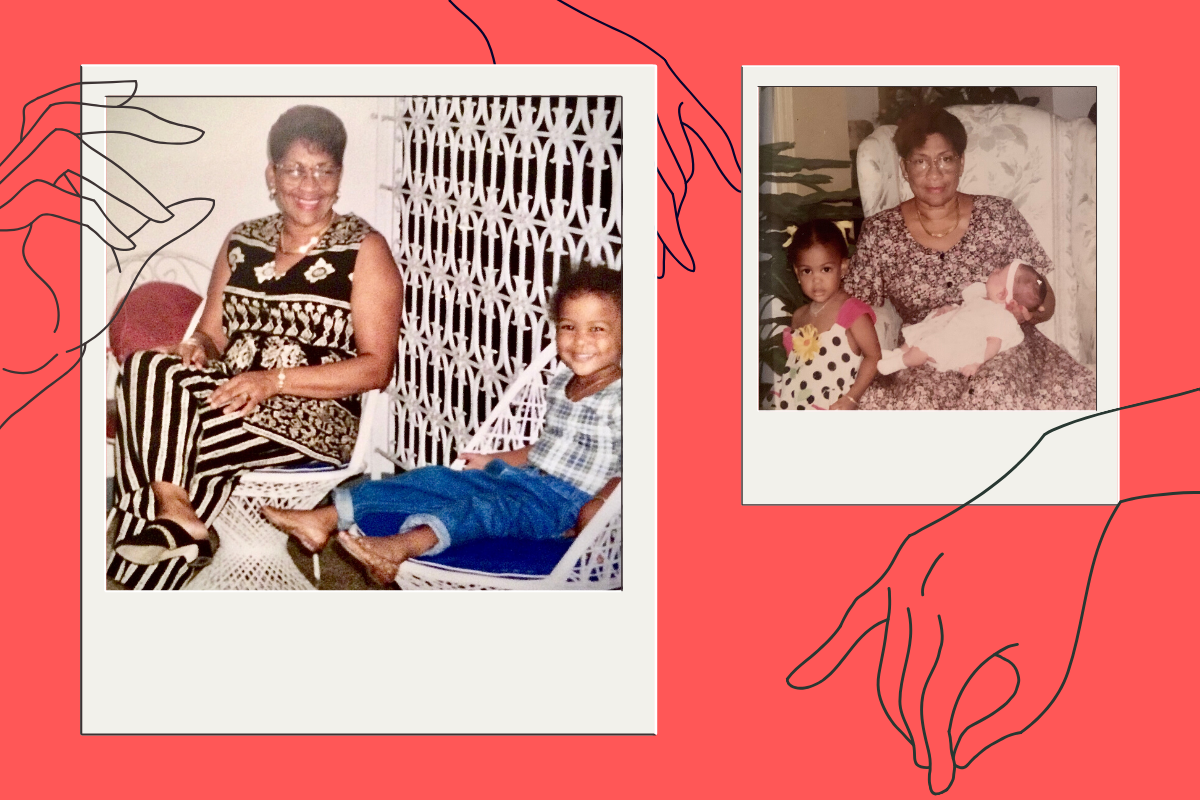

Canva / Images courtesy of Dana Fletcher

Speaking to my Jamaican grandma about her depression taught me how to be a mental health advocate

As a child, Dana's grandmother would often talk about her struggles with depression. This openness would later inform Dana's own understanding of mental health.

Dana Fletcher

18 May 2020

Growing up, I looked forward to spending my summers at grandma Missi’s house in Amity, a small subdivision close to Savanna-la-Mar in Westmoreland, Jamaica. In these pre-internet, pre-mobile phone days, I would find ways to busy myself, avoiding the age-old question, “yuh tek up a book from mawnin?” I rode my bicycle at full-speed on the gravelled roads, made conversations with the cows and goats in the neighbouring fields, smuggled puppies into the house with my cousin and incessantly begged my grandfather to take me for rides where I would sit in the open back of his grey Nissan pickup truck.

My fondest memories, though, are of spending days sitting on the verandah with grandma listening to her stories. She would have some Kenny Rogers or Shania Twain playing in the background while she recounted memories of her young adult years. Sometimes she would tell me about what it was like to court my grandpa, sometimes she would tell me about my mother’s days as a beauty pageant contestant, other times she would tell me about her parents and their days working in the rice fields. The most riveting stories were the ones she told me about her experiences with depression and taking medication for her mind. The word depression was always paired with the statement: “Dis yah sickness, is an ugly feeling. Iz not a physical pain. It’s a mental pain.” She would speak gravely about its ability to “tell yuh some ugly things and mek yuh feel fi do some ugly things”.

As a little girl, I couldn’t quite understand what she meant, but I continued listening nevertheless. This ugly sickness somehow also stretched its way to the neighbour’s daughter who left the island to go to school in England, then came home years later to spend her days locked in the house walking aimlessly in her pyjamas. This ugly sickness put up a fight when grandma tried antidepressants for the first time, making her feel like she was going mad as the walls closed in on her, and she fought off intense urges to ditch her clothes and go running through the fields filled with thorns.

“This ugly sickness put up a fight when grandma tried antidepressants for the first time”

In a country that brutally stigmatises those with mental health conditions, labelling the untreated as “mad” and “sick in the head”, I didn’t recognise the radical and life-saving nature of my grandma’s storytelling until I was much older. She was engaging me in a rich history of knowledge sharing through oral tradition that would later arm me with the language I would need to identify my own struggles with depression.

So when I was 17 years old and in university, living away from my family for the first time, I knew how to recognise when the ugly feelings began to crawl out of my chest and my head. This thing that wasn’t a physical pain, but a mental pain, that was telling me to do some ugly things as the walls closed in, and incited harmful urges in me. While terrifying, it wasn’t a novel occurrence; I had already experienced it through my grandmother’s words. I knew its power and knew what it would do to me if I didn’t try to find some help.

I’ll admit that while going through my own treatment and healing process, I gave in to shame and stigma. I adopted a “stiff upper lip” for fear of being judged, labelled, excluded and misunderstood. For many years, this shame and secrecy served as a barrier preventing me from actively engaging with, and identifying my pain, my vulnerabilities and the parts of myself I deemed most unlovable. It wasn’t until my diagnosis with bipolar II depression in April 2016 that I realised how my fear of being “found out” nearly cost me my life.

“Despite our collective pain, sadness and individual experiences with poor mental health episodes, we were choosing to fight our battles in secrecy”

I started advocating for mental health awareness within my community, following in my grandmother’s footsteps by using storytelling to unmask universal human truths we seem to collectively fear. I began understanding how despite our collective pain, sadness and individual experiences with poor mental health episodes, we were choosing to fight our battles in secrecy, effectively holding ourselves hostage to our fears.

These days, while curating virtual and in-person community discussions on mental health through my advocacy campaign, Embrace Your Unknown, I remain steadfast in my commitment to oral tradition as a vehicle for destigmatising conversations on mental illness. I regularly choose to emulate my grandmother’s levels of vulnerability and transparency, thanking her for giving me a roadmap to a kind of freedom that has been liberating whilst also propelling me towards my own healing.

Engaging in this tradition of storytelling has empowered me to go beyond the lifeless statistics enumerating the gravity of untreated mental illness. It has enabled me to embed my activism in the heart of what mental health advocacy should be: sharing our stories as a tool to validate other’s experiences in the hopes more people will feel encouraged in their choices to embark on their own wellness journeys with the support of their chosen communities.

I think back to my childhood listening to grandma’s stories on the verandah in Amity and am reminded of these words shared by bell hooks in her book, Sisters of the Yam: Black Women and Self-Recovery: “It is important that black people talk to one another, that we talk with friends and allies, for the telling of our stories enables us to name our pain, our suffering, and to seek healing.”

If you or a loved one are if you or a loved one are suffering from depression please seek professional help as soon as possible. More information and online help centres can be found here.