Start caring about Coded Bias, the Netflix hidden gem warning us about AI’s oppressive potential

When algorithms decide who goes to jail, who gets a house, or your social standing in society, it's about time we paid attention

Kimberly Oula

06 May 2021

Have you recently tried to renew your passport via gov.uk and when you upload your photo you’re told “it looks like your mouth is open” but it’s shut? And you happen to be black or brown? Congratulations, you have experienced algorithmic bias! To understand what that means you should watch Coded Bias, a hidden gem of a documentary now available on Netflix that provides a much-needed assessment of artificial intelligence and its possible dangers.

As it follows researchers and organisers that are mobilising for justice in this realm, an issue which may first appear niche or technical quickly hits home as it is revealed how much our daily lives are already being governed by machine learning. We’re introduced to MIT Media Lab researcher Joy Buolamwini, whose relationship with technology is one characterised by curiosity and creativity.

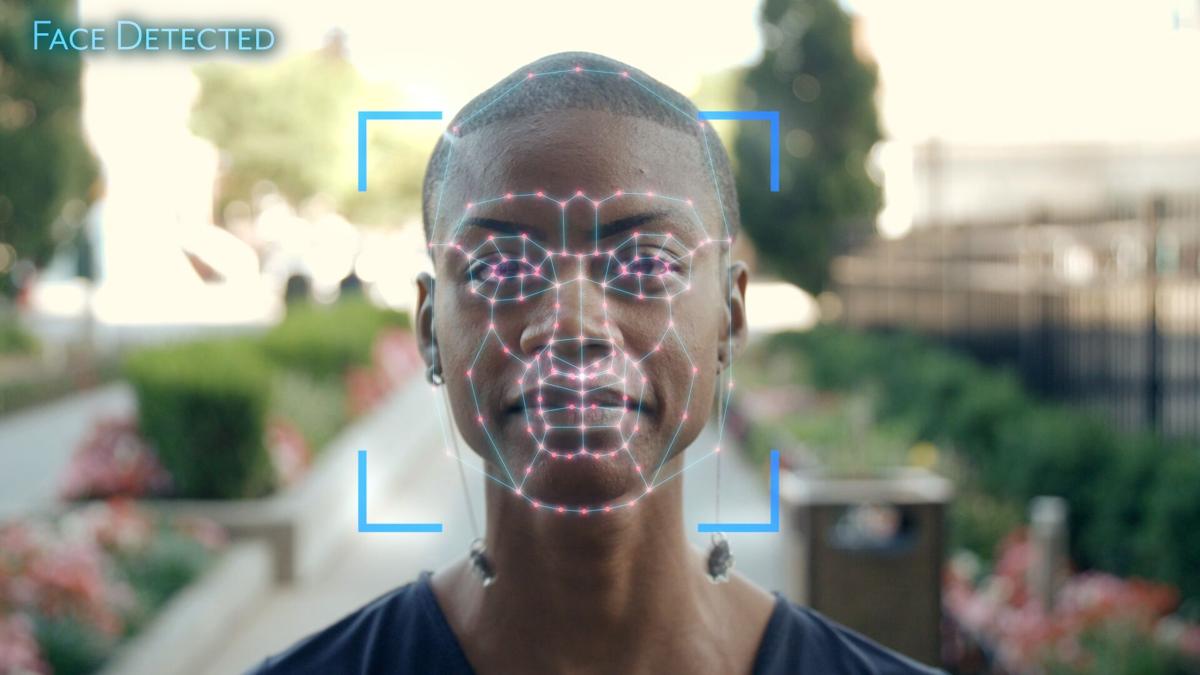

At MIT Labs, Joy inadvertently stumbled across a mammoth issue in tech as she tested out facial recognition. She found her richly melanated skin was not recognised by facial recognition and that she could only be seen when she wore a white mask. From this, we learn about how the police, banks, and major corporations are rolling out the faulty tech with potentially devastating consequences for the already marginalised.

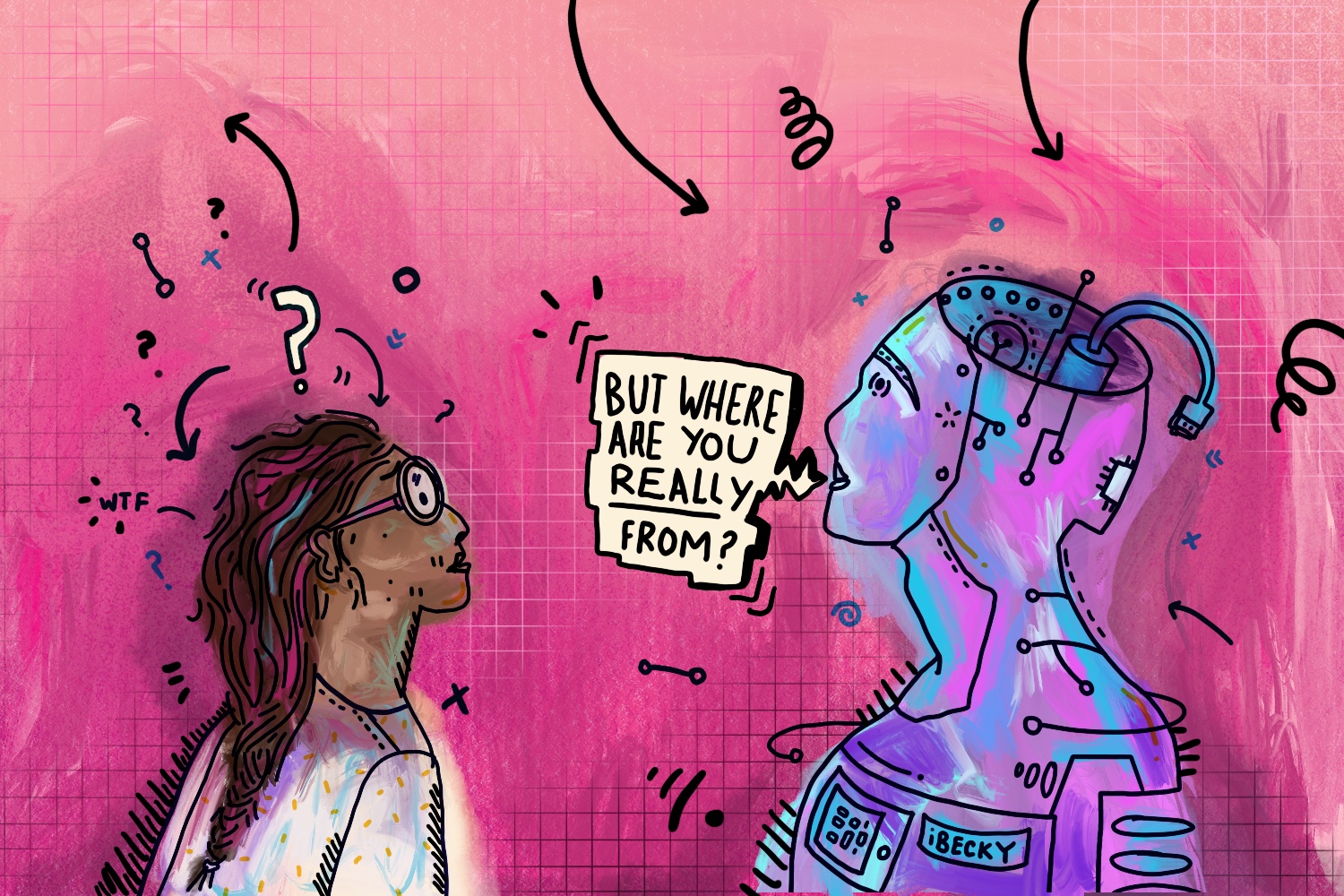

Dr Cathy O’Neil and Meredith Broussard, authors of Weapons of Math Destruction and Artificial Unintelligence explain in Coded Bias what AI and algorithms are mathematics that tries to replicate human intelligence. Dr Cathy describes algorithms as “[using] historical information to make a prediction about the future”. History is often written by victors. So who has agency and liberty when algorithms can be embedded with sexism, racism and any form of oppression? We’ve long suspected that when the robots come, the robots will be racist but here are some other valuable lessons to take from the film.

How race, class and technology overlap

Joy and colleagues featured the gendered shades project in Coded Bias, an experiment that found that commercial companies like IBM Watson, Microsoft and Face++ use facial recognition that performs less accurately for darker-skinned women than any other groups.

Seeing race as technology can help us understand how Artificial Intelligence can replicate racism. Professor Ruha Benjamin who coined the term the “New Jim Code” argues “technoscience is one of the most effective tools for reproducing racial inequality”.

A recent article in Dazed highlighted that as hidden racist algorithms become a part of our everyday life “Black people are likely to be left with less access to housing; when it comes to police databases predicting who will commit a crime, Black people are more likely to be misidentified as targets; and now that companies process job applications via algorithms they filter out the CVs of women and people of colour.”

“A biometric face print is as precious as a fingerprint, something that is usually only taken if you’re suspected of committing a crime.”

Designers and commissioners uphold power dynamics by building their assumptions, oversights and prejudice intocode. The propublica investigation on pretrial risk assessment discussed in the film found “Black defendants were twice as likely as white defendants to be misclassified as a higher risk of violent[re-offending]”. These tools inform judges’ decisions as to if defenders should stay in prison. Effectively AI in policing can just become a digital oppressor which is harder to see or hold to account, baking in the injustice we’re already fighting against.

As well as showing how technology can be racist, Coded Bias illustrates how the researching and testing of it can often treat marginalised communities as guinea pigs. We meet the residents of a Brooklyn apartment based in a predominantly black and brown neighbourhood. Their apartment management installed FR software into the hallway of the residence. “Antisocial” behaviour captured on camera is seen as a risk to the landlord’s financial assets and subsequently harassed by building management. Icemae, a Brooklyn tenant in the building asks “why didn’t you go to your building in lower Manhattan, where they pay like, $5000 a month rent ?”.

Virginia Eubanks shares in Coded Bias that technology tends to be firstly tested in poorer and working communities. Although shocking, it’s sadly not surprising. Neoliberalism encourages thinking that regulation will stifle private sector innovation with red tape. So-called “Red tape” can at times be useful in safeguarding our rights. Seeing working-class areas as testing grounds for “innovation” provides a cloak for practices that might not be publicly acceptable.

While there’s some class analysis in the film what isn’t covered is the outsourced labour from microtask platforms. The amount of data used in AI requires a lot of hands for labeling. In the AI Now report 2018, the authors cite, “The United Nations’ International Labor Organization surveyed 3,500 microworkers from 75 countries who routinely offered their labour on popular microtask platforms. The report found that a substantial number of people earned below their local minimum wage”. To note, I recognise the film scoop is primarily algorithmic bias, however, Coded Bias does touch on who AI is for. Uplifting microworkers experiences helps to interrogate how the application of AI both needs and exasperates class exploitation.

Pay attention to the creeping threat of authoritarianism via AI

AI can be used to maintain social order and political authority. In China, facial recognition is used to support a Black Mirror-style social credit system that rates people based on their digital footprint. It regulates people’s social activities and facilitates the persecution of Uighur Muslims by digitally tracking them. We may look at China and say “Well thank goodness we don’t live there”, as Amy Webb critiques in the film. But there is an adequate concern for authoritarian uses of AI in the West, particularly the UK.

Privacy isn’t a gift from the state, it’s a human necessity. I was shocked by one scene in Coded Bias, where a person decided to hide their face from facial recognition intelligence gathering exercises by the Met Police and was subsequently fined for covering their identity. A biometric face print is as precious as a fingerprint, something that is usually only taken if you’re suspected of committing a crime. However, according to Big Brother Watch, tens of millions of UK citizens have been scanned – and mostly without their knowledge.

“Seeing working-class areas as testing grounds for “innovation” provides a cloak for practices that might not be publicly acceptable.”

We may have safeguards such as General Data Protection Regulations (GDPR) governing how our personal data can be used. But do legislators have the political will to increase liberal values for the regulation of technology? When freedom and privacy is framed as right to give up for security?

With the recent Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill that marginalises Romani Gypsy Communities, gives increased surveillance powers similar to the prevent duty and reduces our right to protest, I am skeptical of our government. After watching Coded Bias, I better understand the vision of abolishing big data. Abolish Big Data, as discussed by Yeshimabeit Milner, founder and executive director of Data 4 Black lives, calls for dismantling structures that concentrate the power of data for punitive actions by redirecting data for the people who need it the most.

Where to go next after the doc

As Joy adorns her cape at the end of the film, calling for you to join the Algorithmic Justice League, what superpowers can you bring?

The case studies shared across the film, highlight the necessity for coalition building. Technologists, community organisers, data journalists, academia, lawyers, legislators need to work together to take action against algorithmic harms. It brought me pure joy, to see Joy conversate and build trust with Brooklyn residents to ask for consent to advocate on their behalf. The Brooklyn tenants and Joy bring together experiential and technical knowledge to build a coalition based on trust.

There isn’t a single Parliamentary petition that can resolve all of the issues highlighted in Coded Bias, as the topic is so vast and pervasive. It includes both public and private sector actors, (supermarkets like Co-op have begun to silently roll this tech out) hence the necessity for political coalition building. Coalitions need a socio-technical lens to understand and combat the many avenues of algorithmic harms.

“As Joy adorns her cape at the end of the film, calling for you to join the Algorithmic Justice League, what superpowers can you bring?”

Relational ethics can help to address algorithmic injustice as described by Abeba Birhane; understanding is prioritised over prediction, we are grounded in the experiences of the marginalized and understand that bias, ethics and justice are always a moving target that can change.

If you work with personal data (e.g email address, gender) think critically about the ways you collect data, choose your variables and models. For example are you invisibilizing non-binary people by not including their gender lables or using models to predict gender without the persons consent? Texts such as Data Feminism, Algorithms of Oppression, Design Justice and Captivating Technology utilise aspects of intersectional feminism and anti-imperialism to assess how we can make better use of data and technology.

You can engage with key public sector influencers impacting how AI is governed; these bodies include the Centre for Data Ethics and Innovation, National Data Guardian, Information Commissioner’s Office, Competitive Markets Authority, DCMS and AI Council. Public sector bodies often request evidence in public consultations, ensuring you have your say.

Lobby and be critical of legislators and understand that algorithmic harm is an international issue, we need to think and learn glocal (global + local). In the USA, cities such as Minneapolis have successfully campaigned for the ending of facial recognition by law enforcement. We can draw from the work of Amnesty international’s #BanTheScan campaign which seeks to ban facial recognition technology for policing.