By Javie Huxley

Stuffed: the new era of British food writing is here

"There needs to be more of an attempt to give communities that don’t often trust the mainstream media a platform"

Tara Joshi

24 Jul 2021

Whether it’s simply writing about the pleasure, romance and meditative immersion of it, about guiding a reader to try something new, or even looking at food within its industry framework – who gets to write about food? Zines, recipes from loved ones and food traditions have been passed down orally for a long time in marginalised communities and beyond. But historically, food writing in traditional British media has been the preserve of a select few.

Obviously, that’s essentially true of all UK’s biggest publications across different subjects. Yet the dominance of the white middle and upper classes on their food pages is especially strange to reckon with when you consider the working-class and immigrant stories behind many of this country’s best-loved dishes. As Skin Deep co-founders Anuradha Henriques and Lina Abushouk said to Huck in 2018, after an issue of their magazine looked at the intersection of food and race: “There is no English history without our histories. Anyone trying to understand how communities of colour have contributed to this country and its culture need look no further than their cupboards and fridges […] We know it’s something that many people turn to for comfort and respite […] Yet to think of food in such romantic terms is to overlook that food shapes and is shaped by money, movements, power, people, conflict and climate.”

British newspapers are made up of restaurant reviews and recipes, rarely considering how food intersects with workers’ rights, poverty, disability or, indeed, immigration. This is not to erase the work of, say, Jack Monroe or Jay Rayner, who have confronted such issues in their writing for the Guardian. But generally speaking there’s a lot to be desired. There’s a perception that food writing in the UK is inaccessible – that restaurant reviewers are a cultural elite punching down, not necessarily interested in the communities within which the restaurants exist; or that cookbooks are a ‘luxury’ and recipes are solely aspirational (and that all of these are being written with a white middle-class audience in mind). For the most part, it is a space that’s considered apolitical.

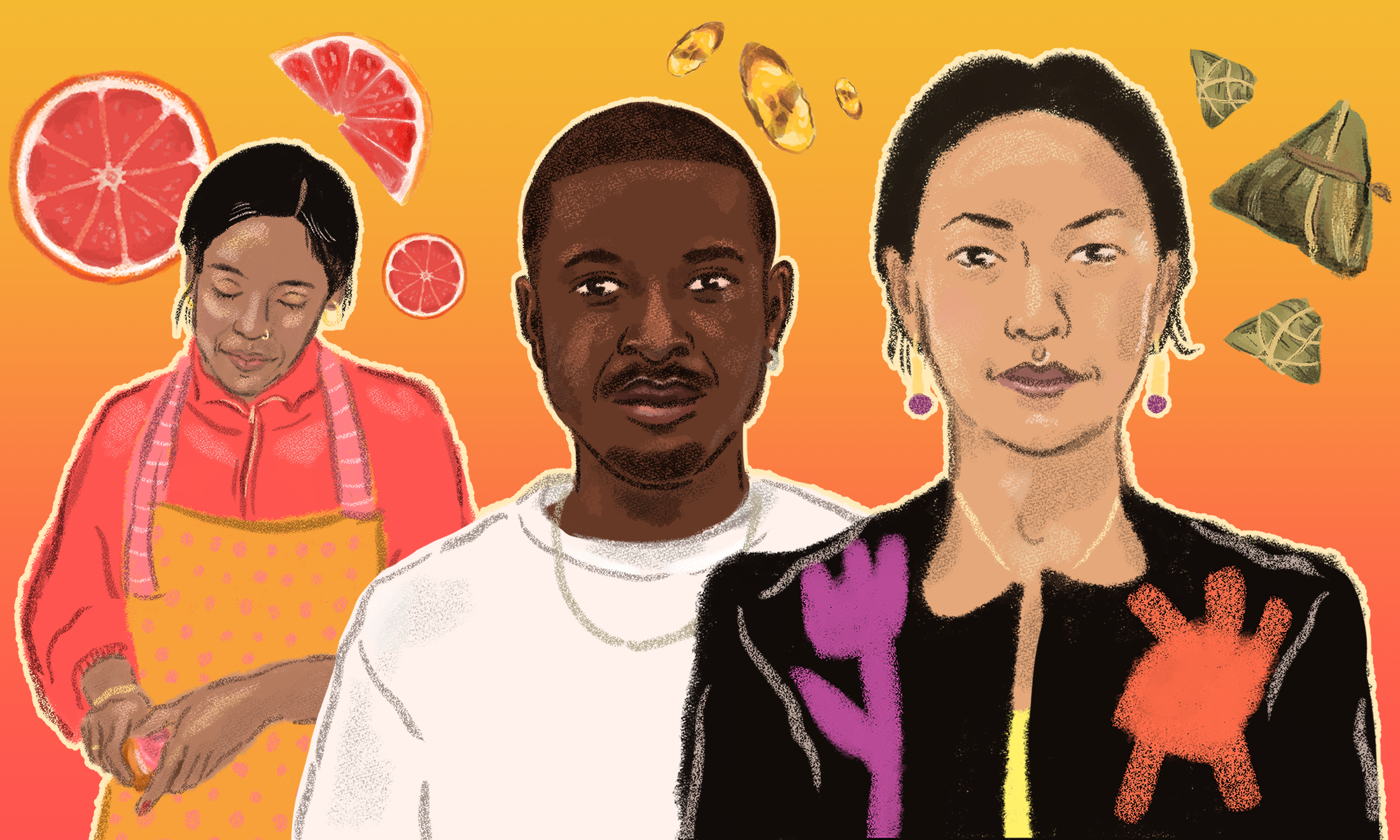

But there are people and groups emerging who seem dedicated to changing this, taking food storytelling into their own hands. Take Anna Sulan Masing, Zoe Adjonyoh, Fozia Ismail, Yvonne Maxwell, Melissa Thompson, and everyone involved in Riaz Phillips’ phenomenal recipe book, Community Comfort (to just name a few!). We spoke to three people who are part of this change, holding existing structures to account as well as using their writing as a vessel to archive community cooking and workers’ stories that were once deemed “too niche”.

“When food’s exclusively in the lifestyle world, it’s difficult to make it non-aspirational, to make it real life”

Ruby Tandoh

“For me, so much of [changing food writing] is about disentangling food stuff from the lifestyle section in magazines and newspapers,” says writer and baking icon Ruby Tandoh. Ruby left her position as a recipe writer at the Guardian back in 2018, citing in since-deleted tweets the elitism, fatphobia and lack of scruples that were all rife in the food world. Speaking over the phone, she continues: “Lifestyle’s a huge element of it, but when it’s exclusively in that world, you lose so much. It feels really difficult to make it non-aspirational, to make it real life. Cooking when you don’t have access to an oven is about life. The restaurant industry is about work and labour. Cooking food that represents who you are might fall into culture. We shoehorn [food] into lifestyle and I think that’s where a lot of stuff gets lost.”

Writer Angela Hui, whose work often weaves intimate personal stories into broader insights about food and society, agrees. “In its current form I think [traditional] food media is written in an aspirational, shallow way without looking further afield and widening its circles,” she says, unpacking how the perception of food writing as a middle-class pastime allows for ostracisation, and for the decontextualising of certain foods. She cites how certain foods have become exciting “brand-new” vegan trends in recent years, when more often than not communities of colour have been eating said food for centuries – take jackfruit in South Asian cooking or seitan in ESEA food.

“There needs to be more of an attempt to give communities that often don’t trust the mainstream media a platform,” she continues. “Parts of the UK media are tied up in racism and bigotry that’s often excused or goes unnoticed. Those that have the power to – journalists and editors working in legacy food media – have a responsibility to call it out, stand up to it and hold people accountable.”

“Growing up, I always thought food writing was either restaurant reviews or cookbooks – no in-between”

Angela Hui

Angela points to food journalist Giles Coren’s Kaki restaurant review in the Times, and Grace Dent’s piece for the Guardian on Soho and Chinatown during the pandemic. The former “transcribes” the phone call Coren had with staff at the restaurant in jarringly offensive terms; the latter finds Dent describing Chinatown’s “shadowy, money-rinsing kiosks”. “These unnecessary and incredibly harmful stereotypes and words play into fear-mongering,” says Angela. “[It’s] whipping up hate and damaging businesses, especially when Covid-related anti-Asian hate crimes are skyrocketing in the UK. They might not be direct, but their words certainly play into it.”

But in 2021, there’s a clear alternative to those legacy publications. Media sites like Eater London (part of a network which also looks at food in North America) and the food newsletter Vittles are representative of a different kind of food writing that’s been stewing in the fringes of British media in recent years, publishing writers beyond those traditionally represented. As Ruby is quick to point out, it might be erasing smaller community-organising histories to claim this is an entirely new phenomenon: “So often this gets framed as ‘there’s the boring, white, wealthy old guard and then there’s this new wave of left-wing food people’. But how true is that? It’s my guess that people have been writing about food in these thoughtful ways for some time, in zines or community recipe books, but maybe just not in the mainstream.”

So what’s interesting about Eater and Vittles is their power to disrupt what is happening in the wider world of British food writing. These are platforms that look beyond the establishment and champion the unsung heroes. They tell the stories of home food, of political contexts, of workers’ rights, of geographies and histories that explain how certain restaurants ended up in specific places. They write about the best value and most delicious cuisine in your area (even if it’s outside the city centre) and things like the regional variants on a good chippy tea. These are the stories shaping online food discussions and, crucially, getting young people – young people of colour – excited about food writing. It’s starting to feel like there’s a space for them in this landscape to not only tell stories that might have once been deemed, as Angela says, “too niche”, but get paid a solid fee for doing so.

“Growing up, I always thought food writing was either restaurant reviews or cookbooks – no in-between,” says Angela, who credits sites like the now-defunct Munchies (the former food section of VICE and now part of the broader publication ) with giving her an outlet to tell more nuanced food stories when she was starting out. “But this year, I think because of Marcus Rashford, food poverty, food stamps, Eat Out to Help Out, more people are realising the conversation is bigger than criticism and recipe writing.”

“If you submit it to me, I’m not gonna water it down or defang it I’m not going to try and push you to make it more understandable for a white middle-class audience”

Jonathan Nunn

For Jonathan Nunn, the creator and editor of the food and culture newsletter Vittles and a contributor to Eater, these platforms are doing well because there has been no real popular alternative. He set up Vittles last year, initially with no long-term plans, just the intention of creating an outlet for people when the pandemic was decimating the restaurant industry. “Within the first month of setting it up, I realised that I actually had a really good opportunity to create something which was bigger than I had initially planned,” he says over a coffee. “It really is this vast, uncontested space within food writing in Britain, which talks about food outside of a very narrow experience – whether that’s the experience of class, of race, of immigration. This genuinely isn’t being covered by mainstream outlets for one reason or another.”

Jonathan explains that there are very few outlets for British food journalism – “and those spaces are mainly newspapers” with many similarities in their food sections. He says the reaction to Vittles made him “realise how many people have been waiting for something like this… for a space to come along to either read these things [articles] or to write them themselves.”

For Jonathan, Eater’s arrival in London signalled the change of the food-writing landscape. “It’s really another vision of London, which wasn’t being seen even in specialist London publications like the Evening Standard,” he says. He discusses how, rather than simply focusing on the same, heavily publicised Zone 1 locations, Eater has moved the conversation further afield – without implying these are “consolation prizes” for those who can’t afford to eat in central London. “Eater really changed the narrative about what is important enough to be written about.”

“There’s definitely a role for raising awareness and sharing these stories… I feel proud when I’m able to do that”

Ruby Tandoh

With Vittles, Jonathan is about applying that kind of philosophy to food scenes beyond London and commissioning the kind of food writing that he would want to read. “If you submit it to me, I’m not gonna water it down or defang it,” he says, “I’m not going to try and push you to make it more understandable for a white middle-class audience. I’m going to treat the audience like they’re adults.”

Between Vittles’ emergence and the resurgence of Black Lives Matter protests last summer, British media is starting to play catch up. “I think editors before will have thought, ‘I’m not going to commission something about a Nigerian restaurant because our readers won’t be interested,’ and you can’t get away with that anymore,” says Jonathan, “While it’s really important to get writers of colour talking about this, that has to be combined with a change in editorial thinking about those things as well.”

Perhaps things are starting to get better in the world of food writing. For all of these writers though, it ultimately comes down to wanting to shine a light on the communities already doing the work in the food world, who maybe weren’t getting that widespread attention. “There are people I know who are running community kitchens, teaching people to cook who might otherwise not have a chance to learn, people saving seeds from being lost – I think that’s so much more interesting than the posturing of someone like me!” says Ruby. “There’s definitely a role for raising awareness and sharing these stories… I feel proud when I’m able to do that. But I see that there’s still so much more to this than what we write. It’s about the people who are actually there, sharing that food in real life.”