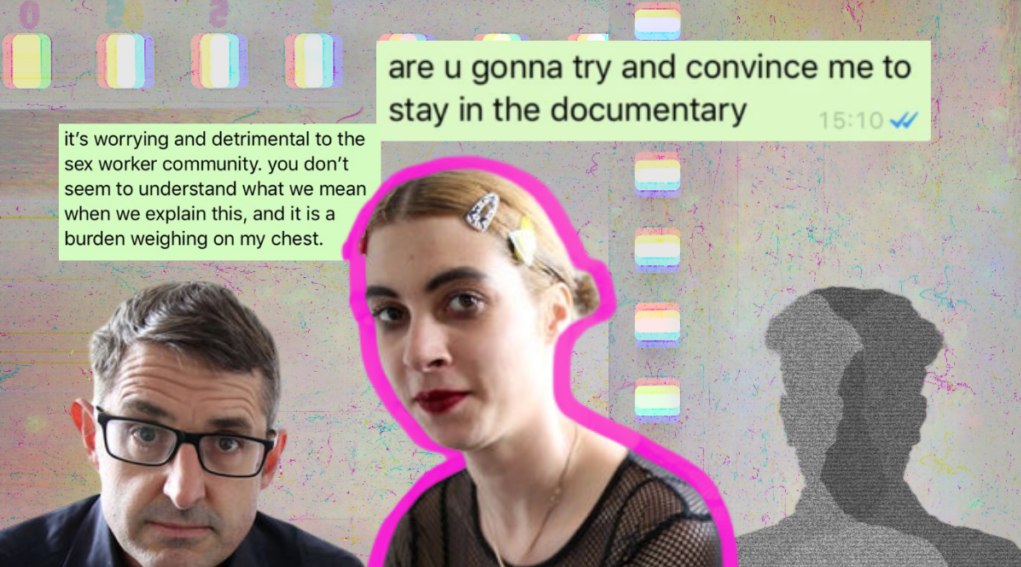

The BBC said they cared about sex workers, so why was I mistreated on Louis Theroux’s set?

Ashleigh shares her experience as a case study in a BBC documentary on sex work.

Ashleigh

03 Feb 2020

Photography via the BBC / gal-dem

Last year, I participated in a BBC documentary on sex work with Louis Theroux and left the experience deeply unhappy. For context, I’m diagnosed with Aspergers, amongst other mental health and physical ailments. I’m mixed Caribbean and British, born and raised in South West London. I’m working class, I’m gay, I am an abuse survivor, still working my way through addiction recovery and completing an MA. Many aspects of my identity were not respected by the documentary makers.

The way the BBC presented me with information felt deliberately manipulative. I was told from the outset that the film would challenge stereotypes about sex workers in an attempt to dismantle and destigmatise the negativity surrounding my work. I was also told there was a former sex worker involved in the production – which I heard from another source later on wasn’t true. This had all been part of why I took this opportunity – I wanted to help educate the public on work that is carried out by some of the most marginalised people.

But my treatment on the show revealed the production team had a shallow understanding of sex work. On set, I felt far from comfortable. If you’ve seen the show, there’s a short clip where I yell, “I’m going to be late”, to which Louis responds that we should get a move on. But his team were the ones making me late – they insisted they hung around to keep shooting even though I was visibly distressed about being late for a client. It rapidly became apparent they didn’t respect my time or what I do for a living –would they have been happy to make me late for a bar shift or any other type of work?

“They hung around to keep shooting even though I was visibly distressed about being late for a client. Would they have been happy to make me late for a bar shift or any other type of work?

The production team also didn’t respect parts of my story. I told them that I wasn’t new to sex work, just escorting, and they initially refused to acknowledge this in the documentary. Originally, I know they had been on the hunt for someone new to sex work, but instead of actually finding someone, they tried to make my narrative conform to the one they had planned. It wasn’t until I was in tears, deep in the editing suite, that they began to acknowledge why it was important that my story was told properly and accurately. This signalled a lack of understanding of the different types of sex work, and also a lack of care in terms of doing justice to case studies.

My autonomy and the validity of my experiences were also constantly questioned. It felt very clear to me that Louis himself, and the production team, didn’t have a good understanding of disability. Firstly, I told them that I was disabled and that I should have had a carer present when signing any release forms (a legal form that gives them the rights to the footage). They also cut interview footage of me explaining that sometimes my autism causes me to crack bad jokes and say things I don’t mean, and just kept in the most salacious remarks. And if you’ve seen the final cut – what’s not shown on TV is that after I poured my heart out to Louis in the pub he asked, “Are you sure you’re autistic?” The question, and the following silence, was deafening. In post-production, I had to ask on multiple occasions for the documentary to even mention that I have autism and their reluctance made me feel like I was begging for their validation. Eventually, they added a voiceover that brings my disability into the narrative, but I had to fight hard for it.

“After I poured my heart out to Louis in the pub he asked: ‘are you sure you’re autistic?'”

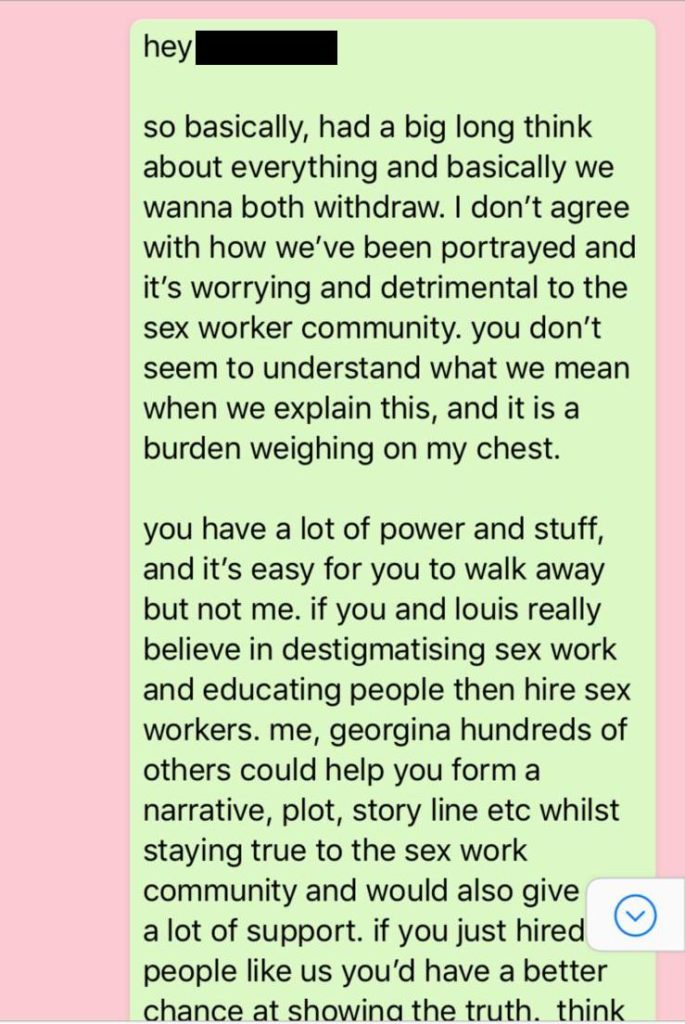

Then, the subtle racism. I am half Dominican and am white-passing. Over the five-month period of filming, I went from having relaxed hair to single plaits, back to my natural curls. But they asked me to get my hair rebraided multiple times for “continuity” – not considering the cost, time, effort or health of my scalp. After a bicker via WhatsApp about what’s best for my scalp and hair health, they let me decide my own hairstyle. But then multiple times on set, a white woman kept touching my plaits saying how “cool” they were. I’m glad you think my blackness is “cool” – you know what else would be “cool?” Not having to deal with basic microaggressions in 2020.

Image via the BBC

A prominent member of the crew did not conduct himself in a way I see as professional upon reflection. We did have a fairly friendly rapport and messaged quite a bit – but at times I felt like it crossed the line considering the power dynamic. I felt so uncomfortable about the whole thing that I formalised a complaint, in which another member of the team claimed my statements were inaccurate. After replying with screenshots, my complaint was escalated to HR. I keep my receipts, sis. But after a long procedure, the BBC’s complaints team concluded there wasn’t “sufficient evidence”.

“I begged the director numerous times to cut me from the documentary completely, but they wouldn’t. Since the documentary aired, none of my family will speak to me”

There were other issues of consent too – for example, I was asked to show my self-harm scars and told Louis about having been abused in my childhood under the intense pressure of filming, and later regretted it. I had only told this part of my past to a handful of people – no family members, and not a single medical professional. I wasn’t ready for it to be out there, nor was I ready for the backlash I’d inevitably receive from my family. The inclusion of the clip is also dangerous for how the community is represented – playing into the hands of stereotypes about all sex workers having experienced trauma.

I begged them numerous times to either cut the clip or cut me from the documentary completely, but they wouldn’t. The BBC’s guidelines for working with contributors state: “when working on long-term productions or with vulnerable contributors, consent is an ongoing process and should be sought each time a contribution is expected”, but that wasn’t the case, and if they cared about informed consent they would have respected my request to be removed. Since the documentary aired, none of my family will speak to me.

They did attempt to safeguard in some ways. I was put into contact with a therapist they had hired, but after everything that happened, I had trouble feeling like I could open up and trust her. I was offered three sessions with her; one pre-broadcast and two post. I acknowledge the kind gesture, but it was, in the words of Jojo, “too little too late”.

For the most part, the show was a blur for me. I don’t want to rewatch it. The narrative Louis superimposes on each interview is “what is best” for me and the other case studies, even though we spend the course of the documentary explicitly telling him. It is exhausting as a community to constantly try to educate the media and the public on the realities of sex work, just for them to hijack the narrative for their own purposes. At the end of the scene where I have a post-trauma cry, Louis’ voice chimes in on the voiceover, commenting on how he doesn’t think my work is enabling my recovery. But after my experience with both him and the makers of the documentary, I really don’t think he is best placed to say that.

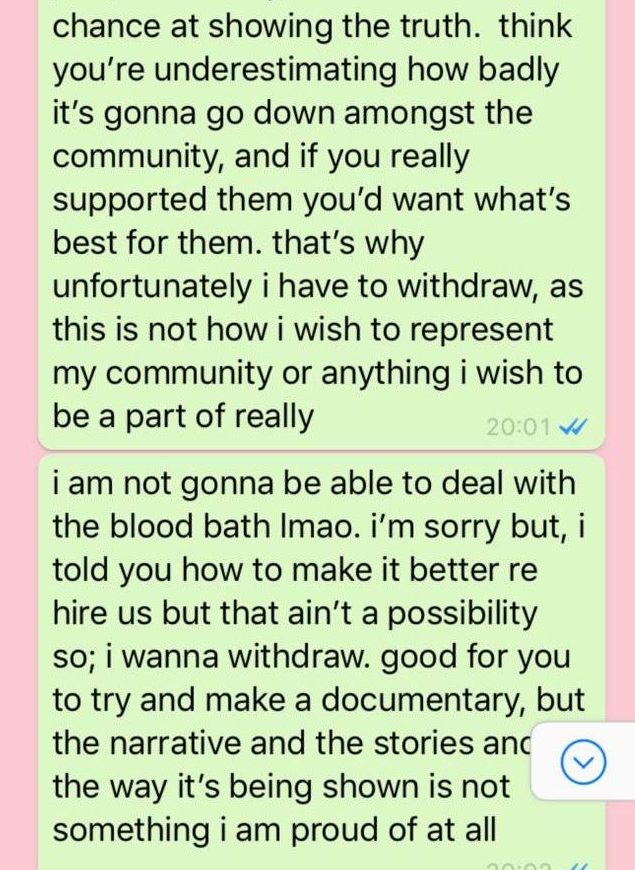

“When contributors are from marginalised and underrepresented communities, documentaries should put the power back in their hands”

Moving forward, if the BBC and other media outlets really want to represent sex workers, the first (and simplest) thing they should do is get us involved in production. The second is to do the necessary research – when my carer Georgina, a fellow sex worker who was cut from the whole documentary, began referencing FOSTA/SESTA, none of the 5+ team stood in my living room, or Louis himself, knew what she was talking about. Without an understanding of the laws that affect sex workers, representations will inevitably be sensationalist. And finally, when contributors are from marginalised and underrepresented communities, documentaries should put the power back in their hands. In the editing suite I was very vocal and ended up crying, and in response the editor literally laughed in my face. When I explained why the narrative the documentary was putting forward was dangerous, she just sighed and shook her head.

I don’t want to imply I’m not grateful for the platform and opportunity the BBC have given me – it’s given me the opportunity to do things I previously hadn’t thought were within reach, like writing this article. I’m also glad the media and the public are increasingly keen to acknowledge our community’s existence, but there’s a fine line between representation and sensationalism. This documentary has created more awareness around our work, but equally, viewers should be aware of how the media can manipulate the people they work with, and lean into lazy stereotypes and tropes. In this case, the production team had a chance to do something good and instead just wanted to grab their payslips and go. You had a chance Louis, a chance to really help us.

***

In a statement to gal-dem, a BBC spokesperson said: “Duty of care to contributors is of paramount importance to both the BBC and Louis Theroux. Louis is a critically acclaimed broadcaster and journalist, with years of experience of making programmes with vulnerable people, for whom he has the utmost respect. Ashleigh raised a number of concerns about her contribution to the programme, and the production team worked with her extensively to ensure those concerns were listened to and, where appropriate, were addressed in the final edit of the programme.

The final edit does lie in the control of the BBC, but the welfare and views of our contributors are always part of our process and it was our genuine view that Ashleigh’s concerns had been resolved.

Ashleigh also raised a number of additional concerns in a formal complaint, which was sent to the production company, BBC Studios, and thoroughly investigated. The result of this investigation concluded that there was insufficient evidence to support any allegations of misconduct.”