The UK’s first black woman history professor is coming to Bristol, and I am overjoyed

Kofo Ajala

19 Nov 2019

Photography via the University of Bristol

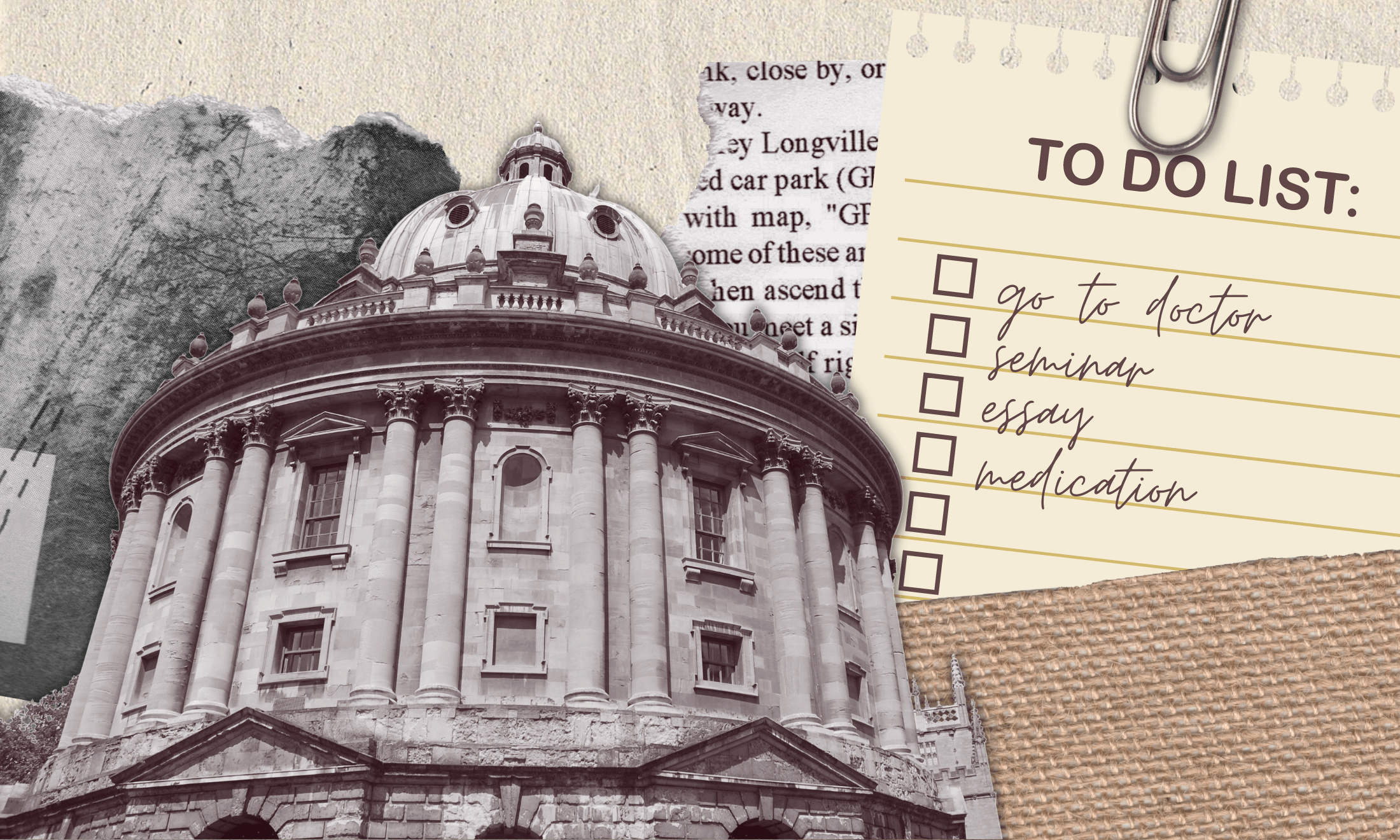

Being a black woman at university often means that from the moment you accept your place on a course, you soon have to acclimatise to being one of the few people of colour in a room. I face this problem to an exaggerated degree as a History student at the University of Bristol – I am the only black woman studying history in my entire year group. So last month’s announcement that the UK’s first black woman History professor would be coming to my university was a complete shock to me.

If I’m being honest, History wasn’t my first choice when deciding what to study at university. Whether it’s family pressures, fears that it won’t lead to a lucrative job or even just that you aren’t that interested, I’ve heard other black British people echo my feelings that the subject doesn’t feel 100% accessible.

But history is such an essential element in shaping identity. History empowers people with a knowledge of who they are and influences what we believe we deserve. As much as people may not see it or even want to see it, history influences everything. But history is also written and accepted by those deemed to have the right to discern the facts from the false. And so far, the history we acknowledge in the mainstream has mainly been determined by white men, and not all of them are interested in revising the narrative.

“Only 25 black women made up for 19,000 of Britain’s professors between 2016-17”

Stories of the marginalised are often in the hands of such people. We should all understand the need to actively safeguard and nurture our history in our communities. But, academia also needs to take the necessary steps in representing black British history and reinforcing the fact that contemporary issues and history go hand in hand. Sometimes I wonder if it should be my job to continue down this academic path and carry the torch for black British historians. After all, only 25 black women made up for 19,000 of Britain’s professors between 2016-17.

As black women move up the ranks of British academia, they see fewer and fewer people that look like them. I mean, I’m literally the only black woman in my year – we’re not exactly off to a good start. So deciding whether to pursue the unchartered waters of academia feels harrowing.

Studying history in a British, majority white institution has taught me a lot about how my education has failed to address race in a nuanced way. When interrogating colonialism and racism in the classroom, you may hear sentiments like “yeah, it was terrible then, but look at how much better things are now”. At times you may also find yourself forced to defend yourself in tone-deaf debates about why British museums are the best place to “protect” stolen artefacts.

For many History students, university is the first time they engage with the past in a way that acknowledges race so prevalently. For lots of white students, it seems like slavery and imperialism are just modules to get a pass mark on, or even to skip altogether. After all, why would you bother studying these topics if you don’t see them as relevant anymore?

“She is hopefully the first of many black British women who will make space for women like me in a subject mostly made up of old white men”

So, when I found out that the University of Bristol, my university, was hiring its first black professor of slavery, I was overjoyed, to say the least. When I saw the name “Olivette Otele” flash up on my phone, I wanted to tell every black girl I knew. In an interview with The Guardian, discussing her appointment to her new role, Olivette stated that she wished for her ongoing project to explore “the way Britain examines, acknowledges and teaches the history of enslavement.”

Her interests go beyond history and into contemporary space and public perception. Like I said, history touches everything and does not only get left in the past. In a university so deeply rooted in the story of Britain’s slave trade, Bristol must do black and brown history justice. She says that she wants to be seen as “a facilitator of a dialogue that needs to take place, and that is about the role of the University of Bristol in the transatlantic slave trade.” How could I not feel inspired?

It’s honestly amazing what representation can do for those who haven’t been represented for so long. For me, even though I have missed the chance to be taught by her, I cannot help but feel inspired by her. She is hopefully the first of many black British women who will make space for women like me in a subject bursting at the seams with old white men. And I just love to see it.