courtesy of the Bishopsgate Institute's LGBTQ+ Library

‘She-men’, ‘ladyboys’ and ‘transvestites’: uncovering trans Southeast Asian archives

Looking through British tabloid newspapers from the 1960s and 1970s shows us how little has changed – both in hostile attitudes and our community’s resilience.

June Bellebono

18 Jan 2022

[Content warning: mentions of transphobia and sexual assault]

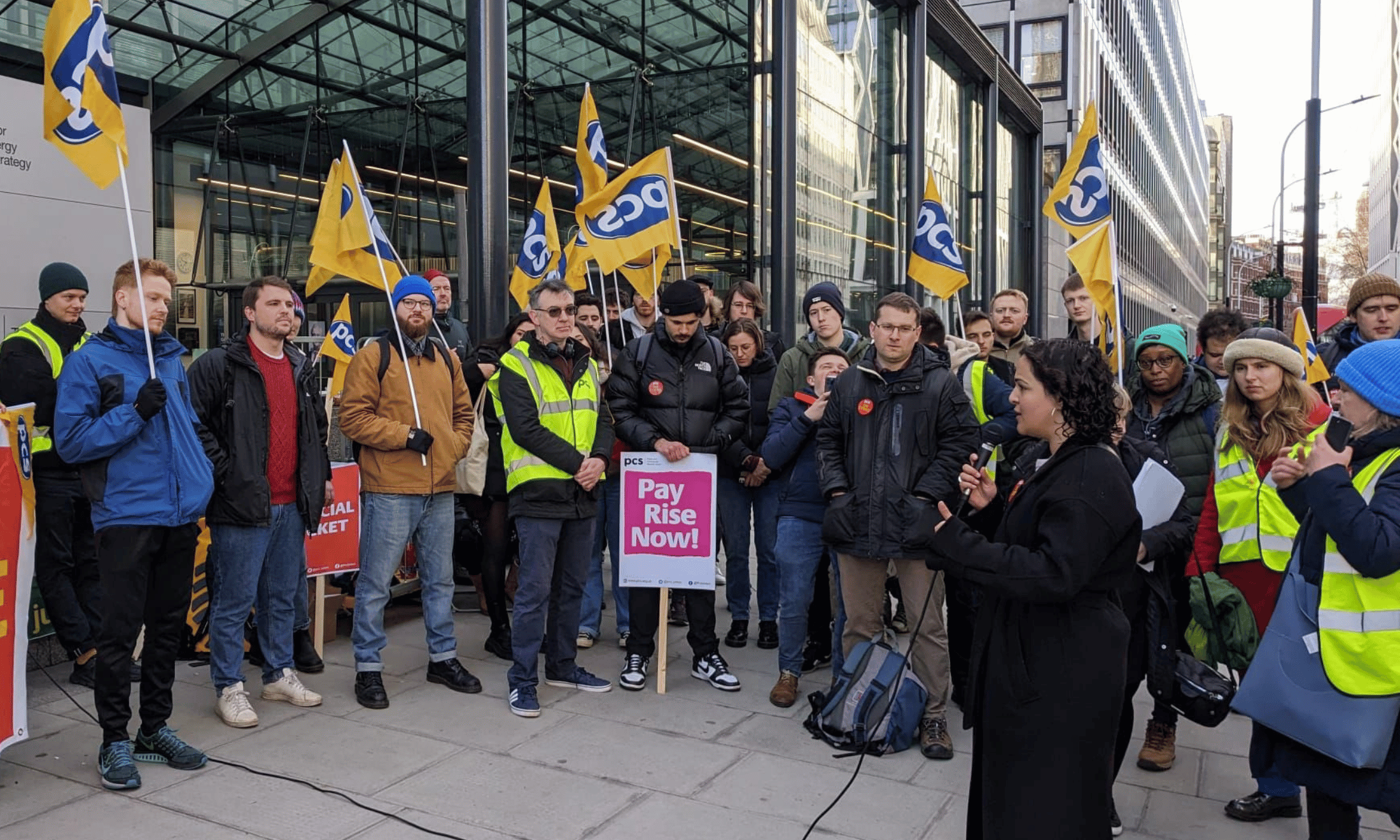

In December 2021, I emailed the Bishopsgate Institute, a cultural centre home to one of the UK’s largest collections of LGBTQ+ archives, with a request. I wanted to explore their material, namely of British origin, on trans women in Southeast Asia, out of personal interest. Vaguely, I expected to find anthropological academic articles with a colonial undertone. I didn’t anticipate the physical and emotional toll I was subjecting myself to when I visited later that month. By the end of the afternoon, my body was uncomfortably stiff, my jaw worryingly tense, and my head spiralling with thoughts. What was meant to be a day of tracing an under-discussed social history ended up being a somewhat masochistic process of exposing myself to one explicitly transphobic newspaper article after another.

The intersection of trans womanhood and Southeast Asian identity is one that for decades has been hypersexualised, fetishised and ridiculed by the white gaze. From the scandal of Daniel cheating on Bridget Jones with a trans sex worker (“I spent the night with a gorgeous Thai girl who turned out to be a gorgeous Thai boy!”) in Bridget Jones: The Edge of Reason (2004) to the 2012 Sky documentary Ladyboys, which opened with the line, “It is said that the best looking girls in Thailand are men”, jokes about trans Asian women have been normalised both on British screens and around the dinner table. Instead of seeing a historical higher level of gender diversity in Asian countries as something to aspire to, the West has been the source of an overwhelming mainstream rhetoric of derision towards trans femininity in Asia, which was also deeply intertwined with anti sex-work messaging

“The intersection of trans womanhood and Southeast Asian identity is one that for decades has been hypersexualised, fetishised and ridiculed by the white gaze”

This also directly contributes to the othering of (both trans and cis) East and Southeast Asian (ESEA) women in the West, who are hypersexualised to a degree that removes their personhood and render them completely passive actors. Their identities ‘don’t count’. It’s why transphobic British lads can go on holiday to Bangkok and happily sleep with trans sex workers, or why white supremacists often enter relationships with Asian women.

Despite being all too sadly accustomed to this knowledge, I still found myself shocked going through those archives.

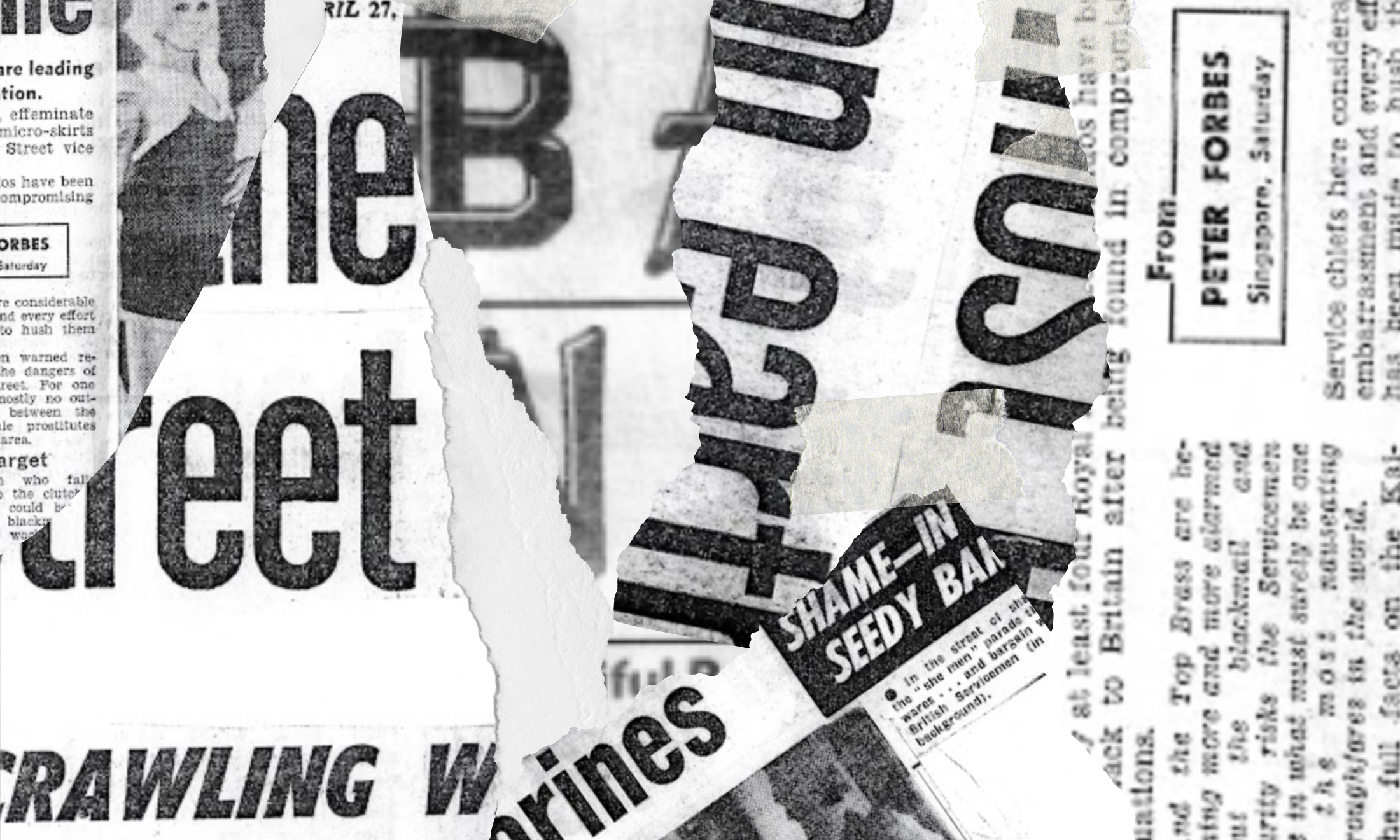

“She-men get marines sent home” and “It’s the most evil street on earth. Crawling with girls… But they’re all she-men!” were two of the first headlines I was confronted by, courtesy of British tabloid newspaper The People, both from 1969. “Where you can’t tell the birds from boys!” screamed another 1974 headline, splashed across a cutting from an untitled publication.. These were just some of the hysterical ways that British journalists – all of whom appeared to be white men – wrote about trans sex workers in Asian countries, like Singapore and Thailand in the 20th century.

The ‘shock’ value of these tabloid scoops were based on exasperatingly redundant, transmisogynistic tropes: that trans women are secretly men (see constant use of terms like ‘she-men’) and that they were out to deceive vulnerable white men (primarily those serving in the military) into having sex for money and ruining their lives. The headlines are quintessential examples of a trans panic, presenting trans women as a great danger, and positioning the men who sleep with them as passive victims, with a complete lack of agency. An obsessive (and catty) focus on aesthetics was apparent – from what trans women wore, to what surgeries they might have had, or ones they wanted to have in future.

The presentation of these women (beautiful and well-dressed) was framed as some sort of villainous superpower they possessed to prey on the Western man. The danger of this narrative has direct implications on the livelihood Asian women that resonates today. In 2021, Robert Aaron Long shot and killed eight people at three massage parlours in Atlanta. Six of his victims were migrant women of Asian descent, who were employees at the spas. In an attempt to justify his crimes, Long told police he had a “sex addiction”, indicating how migrant Asian women are sexualised and objectified to a degree which can render their lives disposable.

What struck me reading through the archival accounts was how many similarities jumped out between the bile produced by the 1970s tabloids and the ‘reporting’ on trans women of all ethnicities conducted by the British broadsheets today. The only major difference? Now, a large number of these trans panic pieces are penned by cis – usually white – women.

“The only major difference? Now, a large number of these trans panic pieces are penned by cis – usually white – women”

In 2020, the Times and the Sunday Times published over 300 articles – almost one a day – about trans people. The vast majority were negative, “hostile” and authored by cis people. Other examples range from the BBC publishing a piece penned by a journalist named Caroline Lowbridge claiming that cis lesbians were becoming victims of predatory sexual advances by trans women (despite offering no evidence for these claims and it later emerging one of the women interviewed had called for the “lynching” of all trans people and was the subject of multiple accusations of sexual assault), to Catherine Bennett in the Guardian weaponising Sarah Everard’s murder to incite the need for single-sex spaces.

Whilst overtly hateful terminology such as ‘she-male’ and ‘tranny’ may no longer be accepted in publications, the arguments are still explicitly derogatory and harmful. Similarly, a good chunk of Western representation of trans Asian womanhood is hypersexualised, often coming via porn. ‘Ladyboy’ videos on porn websites have millions of views, with searches for ‘trans’ porn quadrupling between 2014 and 2017. Like many other identity-centred porn genres, ‘trans’ porn isn’t created for trans people to watch. Scene partners use explicitly derogatory language towards women who are often portrayed as both decisive and servile. Comments left by viewers underneath the videos obsess over the trans performers’ genitals. To see that the narrative surrounding us is still the same as it was fifty years ago, with prominent cis women also now hellbent on inciting hatred towards our community, leaves me disheartened and hopeless, as many other elements in our current state of trans politics do.

“Whilst overtly hateful terminology such as ‘she-male’ and ‘tranny’ may no longer be accepted in publications, the arguments are still explicitly derogatory and harmful”

“We’re holding a mirror to what was happening, but it was very challenging to sort through them because the transphobia is just so casual,” says Rachel Smith, the Bishopsgate Institute’s archivist, after I share my bleak realisation of witnessing history being repeated. I ask Rachel what attracted her to archives. “When you realise, even if you don’t have the language for it, that you’re living on the margins, when you don’t see any kind of future, and you also don’t see any kind of past, it is really isolating,” she replies.

“I remember reading this argument that said that not to be taught about LGBTQ+ people when you’re a child is a kind of conversion therapy because it’s a possibility you don’t even know exists. And that’s why we do what we do here.”

This is the driving force behind the centre being open for donations from all members of the community rather than seeking out items directly from established organisations or individuals: it encourages the celebration – and memorialisation – of everyday queer life, and of identities and stories which are not remembered elsewhere.

I leave the archive feeling torn. On the one hand, I can’t shake off the violent bile I read for hours. But I also find myself experiencing a slight sense of gratitude, with Rachel’s words about learning about our past triggering possibilities for our futures echoing in my head.

“Despite the stories of the Southeast Asian trans women in those articles being derogatory, reading about them also brought me the joy of seeing that they were there”

Despite the stories of the Southeast Asian trans women in those articles being derogatory, reading about them also brought me the joy of seeing that they were there.

The Institute’s Beaumont Press Cuttings Collection includes one newspaper referring to a trans woman as a: “gorgeous creature in a turquoise microdress mincing through the crowd, swaying, smiling”. It’s a description that resonates deeply with the magnetic energy that trans feminine people I know and love exude. Phrases like “brazen and bitchy, the ‘girls’ desperately try to outdo each other” reminds me of the shady sense of humour which characterises so many of my trans friendships. In one newspaper cutting from 1974, a woman in Bugis Street in Singapore tells a reporter that “we run the show ourselves and live together in a big apartment block. Every year we have a beauty contest – last year I won,” which sounds just like the sense of community my trans sisters hold today.

Being a trans person of colour in the UK today often feels like a relentless obstacle course, between endless waiting lists on the NHS, to medical racism. Accessing hidden histories, despite the defamatory nature of the medium they were wrapped in, filled me with a degree of validation and reassurance.

Most Asian countries are still fighting for legal gender recognition, which is in itself a result of a colonial-era homophobic law. But that does not take away from trans Asian women still living in their authenticity, and having done so for decades. The knowledge of this history incites a drive in me to fight for trans liberation, to build community, to practice authenticity, and to carry this legacy.

June Bellebono’s essay, Ladyboy, appears in East Side Voices: Essays celebrating East & Southeast Asian Identity in Britain, published 20 January 2022.

Britain’s policing was built on racism. Abolition is unavoidable

How Pakistan’s Khwaja Sira and transgender communities are fearing and fighting for their futures

Their anti-rape performance went viral globally. Now what?