Being cooped up at home because of the pandemic is a part of many people’s lives that they’d prefer to forget – sorry for the trigger. But, for artist Tschabalala Self (the T is silent) the domesticity of that chapter has become a prevalent theme in her recent exhibit Home Body. “It relates to my own experience of being in the home and watching everyone globally go through that moment of introversion,” the painter says to gal-dem over the phone. She notes that despite starting to explore the topic in 2019, before coronavirus took over the world, she “got into the thick of making these works” during that period. “The level of fear and paranoia that was sparked because of the pandemic caused many people to do a lot of introspective work,” she adds.

Tschabalala is soft-spoken but still manages to articulate herself with authority. In our conversation, she often tries to distance herself from her paintings. “I feel like it’s not that interesting,” she says of relating her work directly to her own life. “The challenge of an artist is to make something that’s meaningful to all people, and it has to be rooted in something that’s outside of just your own lived experience.” The 32-year-old uses her own existence to “access universal philosophies”, she says. “Ultimately, I want to make something that’s about more than just me because I’m not making it to understand me as an individual. I’m making the work to have a better understanding of life in general.”

Born in Harlem, New York, and now living in Connecticut, Tschabalala rose to prominence in 2018, three years after completing her MFA at Yale University. That same year, she became an artist-in-residence at Moma PS1, and by the following year, her piece ‘Out of Body’ (2015) had sold at Christie’s for almost five times its estimate at £371,250. ‘Out of Body’ (2015) is a multimedia piece using oil paints and fabric to depict Black female figures in a way that is exemplary of Tschabalala’s distinctive style: rich and earthy tones mixed with the colourful patterns of the materials she uses, her Black subjects frequently having large bums and prominent breasts.

According to the artist, critics often describe the bodily characteristics of her figures as “exaggerated”, an adjective she doesn’t appreciate. For Tschabalala, identifying her work in this way is “anchored in Eurocentric beauty ideals”. Some have gone as far as to use the word “grotesque”, she adds. “I’m coming from a different cultural perspective. Being Black-American, there are very different beauty ideals, and my figures are aspirational towards those.”

Beyond physical attributes, Tschabalala’s paintings also focus on specific environments. “I previously worked primarily on the bodega and then briefly a series of paintings that looked at the street,” she says. In 2019, her exhibition Bodega Run at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles explored corner shops as an integral part of local communities. A natural progression from this was to look at more insular settings. “Bodegas are both public and interior spaces,” she says. “I wanted to look at a private space that was also interior.”

This new focus has taken Tschabalala’s European audience by storm over the past year. In 2022, the artist held her first European institutional show at Le Consortium in Dijon, France, which is on until January 2023. She then had a solo show at Pilar Corrias Gallery in London titled Home Body which ended this December. Alongside her London show, her first public sculpture has been on display at the northern entrance to Coal Drops Yard in King’s Cross since October and will remain there until the end of this month. She will also be showing at The Kunstmuseum St.Gallen in Switzerland in February. Last year, she also found time to delve into the fashion world with a colourful Ugg collaboration that combined her painting styles with boot design resulting in a striking array of cosy collectable styles.

“Women have so many expectations when it comes to the home and the house – something that’s relatively cross-cultural”

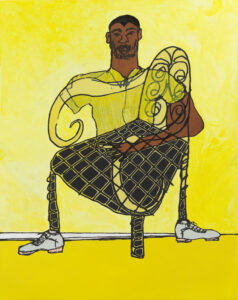

For Tschabalala, the home is a political space that exposes the vulnerability of being a human. She is particularly fascinated by “the fact we need this exterior thing outside of our body to protect us and also all the different emotional, social, political and personal obligations and constructs that take place in this location,” she says. A number of her works show people in deep moments of contemplation within their homes. In ‘All Night’ (2022), a woman dressed in a vibrantly patterned outfit sits by a lamp gazing into the distance. “That work is about loneliness and someone being very much in their own thoughts.”

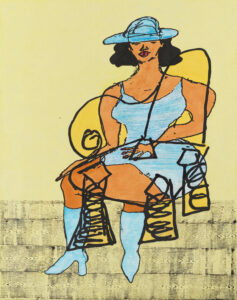

Part of Tschabalala’s interest in the home is its association with womanhood, even in vastly different communities. “Women have so many expectations when it comes to the home and the house—something that’s relatively cross-cultural,” she says. As we know, ideas surrounding women and the home can be restrictive, but Tschabalala turns this idea on its head. In ‘Red Room’ (2022), a woman made entirely out of velvet reclines on a piece of furniture, one of her arms resting on her head as she gazes directly at the viewer. “You see a figure who is being more extroverted taking control of the space that she is inhabiting,” Tschabalala says. “She begins to dominate the space as opposed to being oppressed or consumed by it.”

That said, not all of Tschabalala’s work shows women or people alone. Her piece ‘Madly’ (2022) shows a couple embracing, almost conjoined. “It shows a moment of togetherness within the home,” she says, noting that it’s a scenario that many people desire to have. “That’s the most aspirational story about the home. In the best-case scenario, [the home] doesn’t become a site of isolation. It becomes a site of togetherness.”

While the pandemic may have changed our perspective of our homes, Tschabalala shows that homes are still multifaceted environments that can conjure up various emotions and experiences. “It’s about how people become a part of their environment for better or worse,” she says. “Maybe they’re a part of it because they are at peace in that space, but maybe they’re stuck. It’s somewhat unclear as to what exactly is going on.”

The contribution of our members is crucial. Their support enables us to be proudly independent, challenge the whitewashed media landscape and most importantly, platform the work of marginalised communities. To continue this mission, we need to grow gal-dem to 6,000 members – and we can only do this with your support.

As a member you will enjoy exclusive access to our gal-dem Discord channel and Culture Club, live chats with our editors, skill shares, discounts, events, newsletters and more! Support our community and become a member today from as little as £4.99 a month.