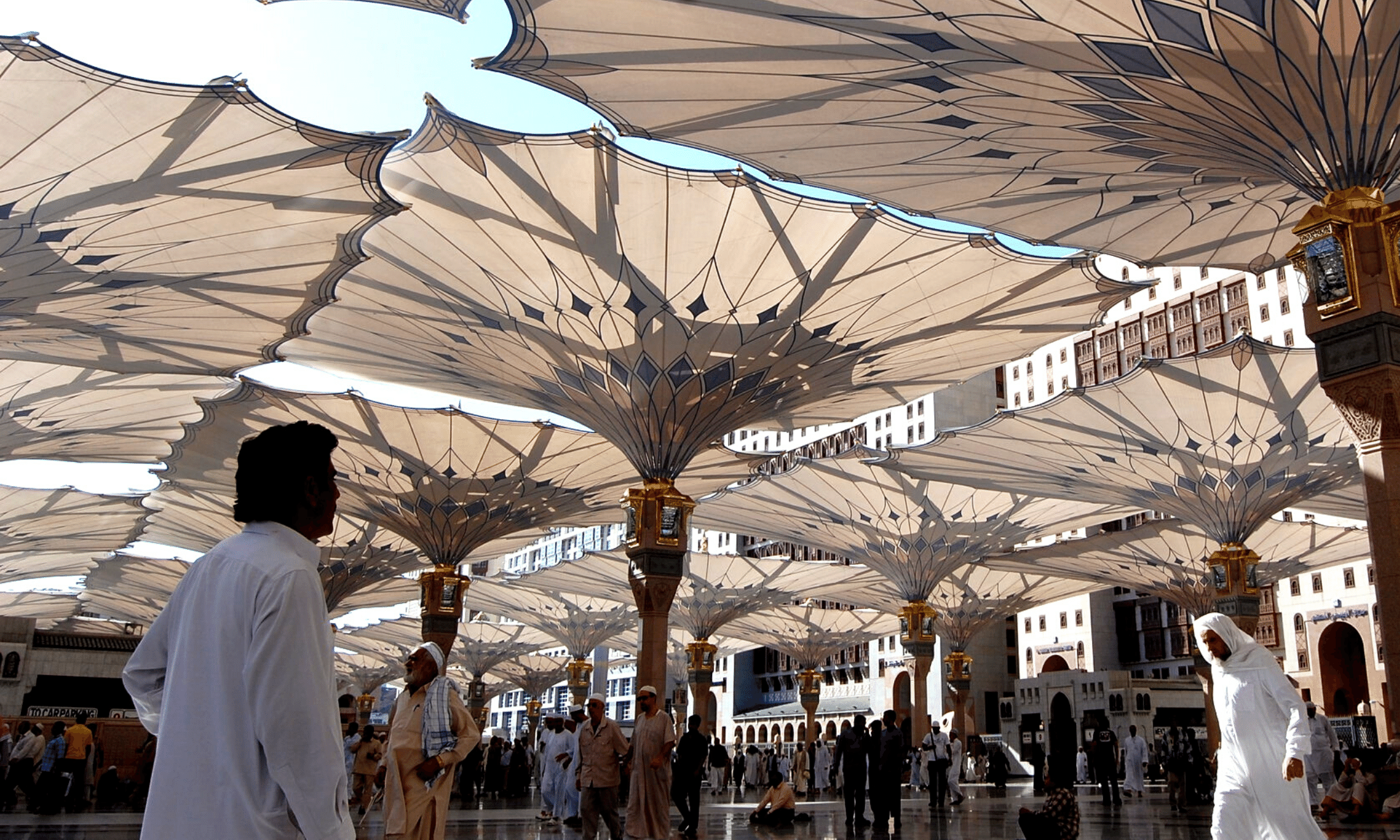

Unsplash/Canva

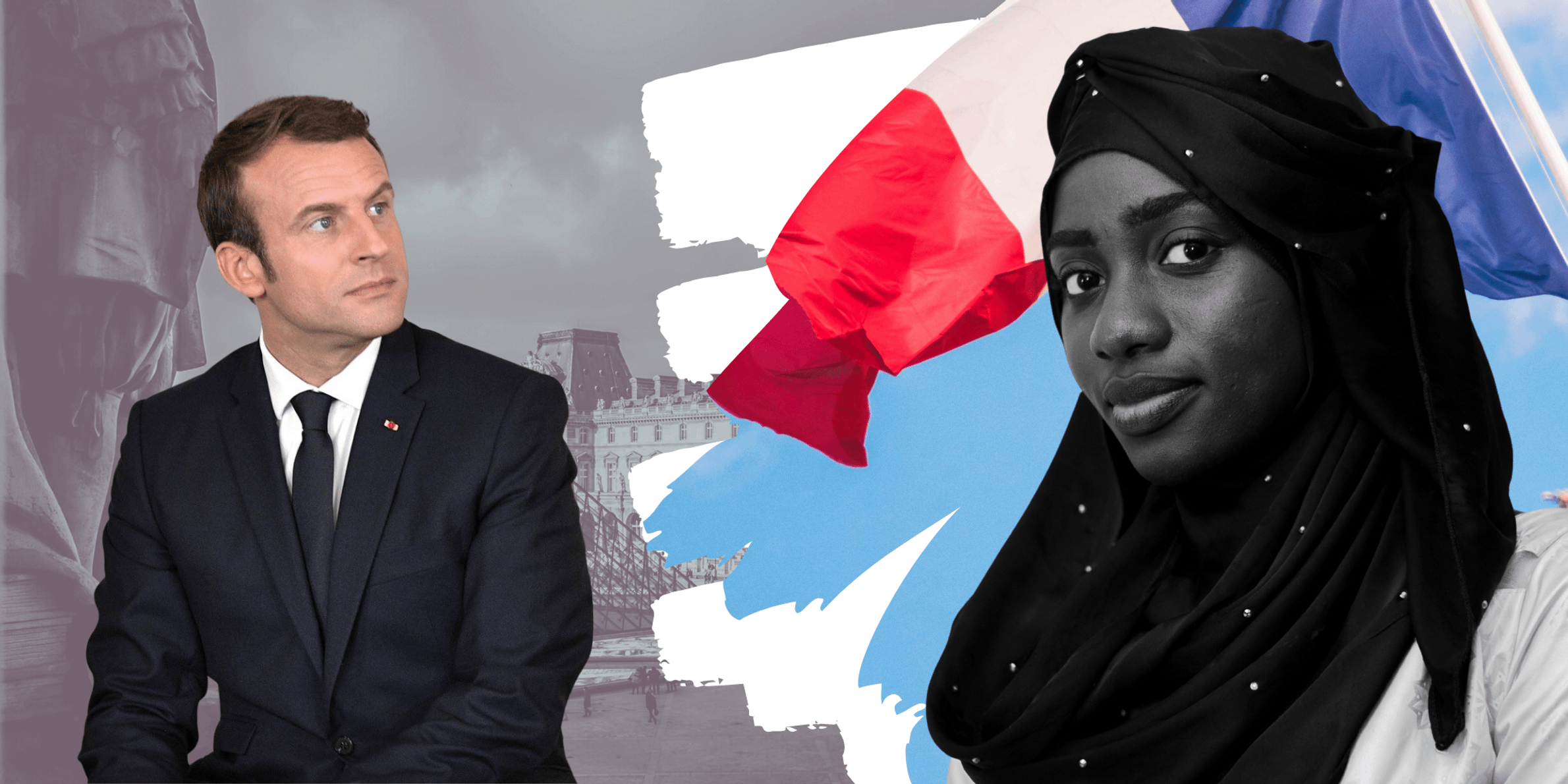

Unveiling France’s hidden histories in Algeria holds the key to understanding its modern Islamophobia

Emmanuel Macron's crusade against France's Muslim population continues a dark policy that began in 1830.

Hanna Bechiche

26 Nov 2020

Credit: Unsplash/Canva

“Unveil yourself! Aren’t you pretty?” read the colonial posters that covered the walls of Algiers in the 1950s. At the time, my grandmother would routinely be forced to participate in public “unveiling” ceremonies that consisted of French policemen burning women’s veils on the public square.

Last summer, my hijabi friend and I were stopped by a French woman on the streets of Paris. She insisted on giving us a speech on French Republican values, and went on a tirade about how veiling meant accepting oppression. “Aren’t you pretty? Unveil yourself!” she said.

These two confrontations are separated by time only. In recent year, French president Emmanuel Macron has identified Islam as threat to the Republican values, assuming that Islamic teachings and anti-French sentimentality were the sole reasons behind recent terrorist attacks in France On 18 November, he announced new measures to fight “Islamist separatism” through control of Muslim officials and children’s private education.

But none of this is new.

In June 1830, the failing French Bourbon monarchy launched a military campaign in the Algerian capital, as a last bid to gain popular and electoral support. What was supposed to be a political showboat quickly turned into a genocidal conquest which killed a third of the population. In the course of this invasion, military strategies were largely drawn along religious lines. To French officials, Islam was the biggest obstacle, a “belligerent religion” that needed to be quelled and controlled. A civilising mission was launched to justify France’s imperialist expansion.

“Only people who had been educated in French universities and proved their loyalty to France could be appointed as Imams”

Algeria’s population was hierarchically organized into simplistic categories and either labelled “Muslims” – who made up three quarters of the population – or “indegènes”. People were denied French citizenship unless they rejected Islamic law, and were also subject to the Native code (Code de l’Indigénat). The Code ensured Algerians endured an inferior legal status and subjected them to a series of repressive laws: the interdiction to travel beyond their counties and buy livestock without a permit, the enforcement of forced labor and dress codes, the implementation of curfews, to name a few.

From 1881, Algeria became an official extension of France, a “little France” where European settlers moved en masse. To consolidate French rule, the process of assimilation was imposed, and French identity was starkly defined against the culture and religion of the indigenous population. The goal was to create a “French Islam”, one that answered to the colonial administration. For example, only people who had been educated in French universities and proved their loyalty to France could be appointed as Imams.

Blatant hypocrisy was rife: while in French-Algeria the colonial government was deeply involved in the population’s religious affairs, in France itself, religious freedom from state interference was widely promoted – and celebrated. Even after the banner of Laïcité (a concept of state secularism) introduced via legislation in 1905, secularism did not reach African shores. Why? Because letting go of the government’s involvement with Islamic institutions would mean losing control of the only means to assert command over the native population. Officially, the excuse given was that Muslims couldn’t understand the concept of separation between religion and state. If this rings a bell, it’s because this claim is still widely professed in France today.

“In Algeria, natives were called ‘French Muslims’; in France, Algerian migrants were called ‘Algerian Muslims’”

When the Algerian War for independence broke out in 1954, French efforts to exert control over Muslims intensified and led to the implementation of virulent anti-Muslim decrees. For the rebelling National Liberation Front (FLN), Islam was the central pillar of the emerging Algerian identity. So to the colonial government, targeting “French Muslims” was synonymous with targeting “rebels” (as the French state dubbed them) or “nationalist terrorists”, usually resistance fighters who were returning the colonial violence back to sender.

In France, Algerian immigrants summoned to rebuild the country after World War Two suffered the same fate. French police assumed the guilt of all Muslims until proven innocent. In October 1961, a curfew was implemented in Paris. The decree enforcing it read: “It is advisable in the most urgent way for Algerian Muslim workers to refrain from circulating at night in the streets of Paris and its banlieue, more particularly from 8:30pm to 5:30am.”

Note the constant contradictions—in Algeria, natives were called ‘French Muslims’; in France, Algerian migrants were called ‘Algerian Muslims’. These ambiguous identities and attached violent persecutions further estranged Algerians living in France from a society that already treated them as second class citizens and threat to national security.

On paper, French colonisation ended in 1962. Today, France still promotes a model of “Frenchness” which was created and pioneered through the exclusion of Algerian Muslims and their forced integration. Just like natives couldn’t be given French citizenship unless they adhered to a “French Islam”, the only way for the North African diaspora to be French is to entirely shed their cultural heritage. Macron stated it clearly in his 2 October speech – France is “not the sum of multiple communities but one single community.”

For Macron to accuse Muslims of promoting separatism is entirely historically incorrect. Separatism was never promoted by the colonised migrant population in France; instead it has always been the basis upon which the colonial administration and military divided and conquered. The colonial enterprise has always pitted French Muslims against French settlers, and the Islamic Algerian national identity against the French Republican national identity

“Decades of overt silence on the everlasting trauma of colonial violence, economic marginalisation, and insidious Islamophobia have created France’s own boogeyman”

Today, France’s colonial history is taboo. Largely ignored in school programs, dismissed as something of the past, the pervasive and traumatic legacy of a century and half of ruling over others is constantly negated by the government.

It’s time to stop analysing the recent tide of terrorism through the lens of Islamic teachings and instead examine societal factors that lead to would-be terrorists becoming disenfranchised. Macron himself acknowledged that France has created its own “separatism” and fostered “economic and educational difficulties” for Muslim citizens. Yet he continues to pursue Islamophobia as a national policy.

Portraying an idea as broad and as vague as “Islamism” as the enemy is no more productive than asking Muslim women to unveil for a week to show ‘solidarity’. Instead, the government should study how France has excluded Muslims throughout modern history and understand how this continues to shut people out of society, ripe for radicalisation. Decades of overt silence on the everlasting trauma of colonial violence, economic and social marginalisation, rampant discrimination and insidious Islamophobia have created France’s own bogeyman.

Britain’s policing was built on racism. Abolition is unavoidable

How Pakistan’s Khwaja Sira and transgender communities are fearing and fighting for their futures

Their anti-rape performance went viral globally. Now what?