Serina Kitazono

Wanderthirst: my first time in Nairobi felt like stepping through a looking glass

How an internship’s cultural exchange programme opened Rachel Chin’s eyes to the similarities between Kenya’s capital and her hometown of Kingston, Jamaica.

Rachel Chin

29 Jul 2022

Every time I stepped outside, the sight of it all pulled the air out of my lungs.

Nairobi is enormous. The mind numbs and the eye waters. I simply could not fathom how any place could be so big. You have to understand that in Jamaica, things end. The mountains split the sky, and eventually, you will reach the sea. In Kenya, the land goes on and on before it fades into the horizon.

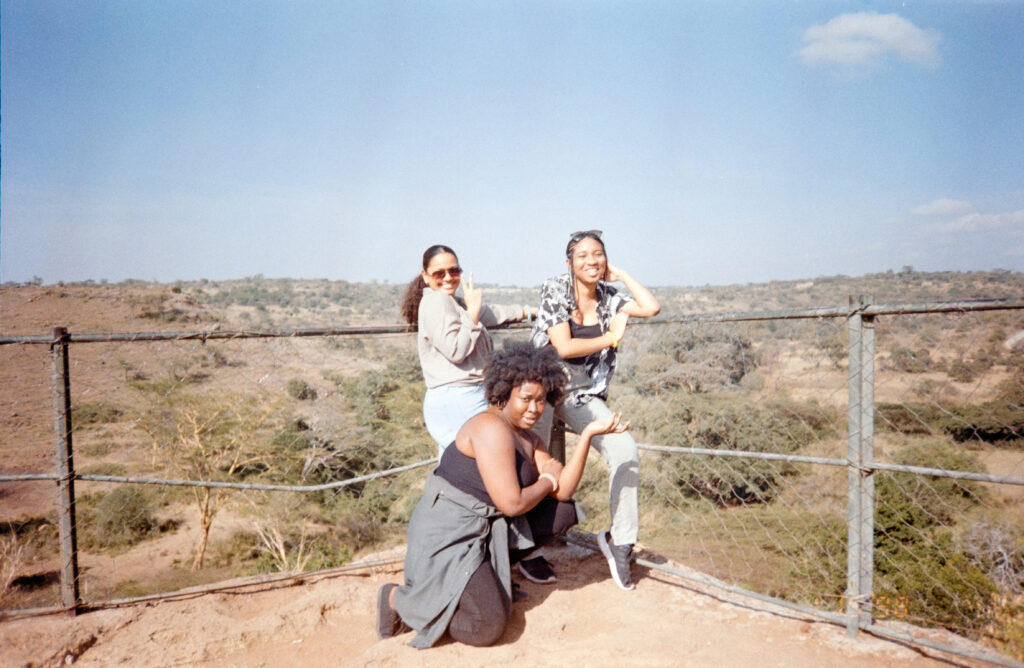

I was in Nairobi in March 2022 on business, mostly, as one of three interns from an arts non-profit. We’d journeyed to Kenya’s capital city from Kingston over the course of two full days for a three-week-long cultural exchange. We’d learn from an artists’ collective based in Nairobi, following their communal process from project development to production.

This was the first time I or my fellow interns had been on ‘the continent’. We’d heard that Nairobi was a ‘modern’ city and that it was even ‘developed’, but we’re from the Caribbean and we know how loaded those terms are. They imply a Western standard of economic growth and wealth – and places like Jamaica don’t exactly make the cut. Over our Zoom introductions, our hosts digressed often about how similar Kingston and Nairobi sounded.

But nobody was quite sure what to expect.

We landed at midnight. On the way to our Airbnb in the Central Business District (CBD), the representative from our host organisation warned us about the worst times to get around as morning and evening rush hour ram the streets for hours. The roads are the only way around the massive metropolis, but traffic in Nairobi, as our rep cautioned, is murder.

“As a Jamaican, I recognised myself in his shrug at the part of the country meant not for its people but its paying guests”

The other interns and I had to take her word for it. She was in charge of our transportation after all, and the only context we had was this taxi ride under skeletal overpass construction and skyscrapers. Even in the dark, Nairobi loomed overhead.

So did the Covid-19 pandemic. Our rep tested positive the following day. And so the three days they’d given us to recover from jet lag stretched out into nearly a week. As we waited for our itinerary to update, we managed to book a Sunday safari into Nairobi National Park, with stops at the Sheldrick Elephant Orphanage and the Giraffe Centre.

In the midst of the sunrise, the first thing we spotted was a solitary giraffe ambling slowly across our path. We lost our collective minds. It was incredible, unbelievable – standing out on the open canopy of the bus and gazing at a landscape that stretched far beyond our imagination. Wildlife, like zebras and rhinos, gathered at various points. The views moved us, constantly, to silence.

One of the interns asked our driver what being there was like for him, if it meant anything. He laughed. Of course not – this was for tourists.

As a Jamaican, I recognised myself in his shrug at the part of the country meant not for its people but its paying guests. It was strange to realise the tables had turned, and I couldn’t help but cringe to remember that now, I was the tourist.

We were also not here on vacation, and we hadn’t exactly budgeted for one. Aside from this glorious Sunday and fermenting inside our accommodation, the most we’d done was take a taxi to the high-end Westgate Shopping Centre for groceries and foreign exchange. Then we took another Uber to Yaya Centre, another shopping mall in affluent western Kilimani for another grocery run. And then we journeyed to The Hub, which – rule of threes – was another shopping centre in another upper-class neighbourhood, Karen, on the west side of the city. That first week, we spent so much time in cars that half of all I saw of the city was through Uber windows.

But the gridlock traffic gave us plenty of time to reflect. Kenya and Jamaica were both colonised by the British, who left behind extreme economic inequality in both countries. Gated upper-class residences, like where our Airbnb apartment was located, are walled off from the world outside, a sprawling network of informal settlements. We’re familiar with this sharp kind of contrast since Kingston operates on similar divides. Nairobi felt a lot like home.

By the second week, our internship could finally get underway. We shadowed our hosts during research at a Bookbunk library in Makadara. A non-profit that restores libraries in Nairobi, Bookbunk has transformed the branch into a thriving community space. Unlike the high-income CBD and western neighbourhoods we’d spent so much time in, deeply entrenched government neglect is apparent in Makadara. Volunteers and staff practically glowed when recounting how the derelict building was filled first with repairs, then books and artwork, and then a steady stream of visitors.

Meeting and speaking with everyone at Bookbunk motivated me to start meeting more Kenyans and to learn even more about their perspectives. I mapped out a kind of contemporary art tour of the city for our internship and began emailing.

“Everyone we met was welcoming and engaging, interested not only in our work but what it was like, as Jamaicans, to visit”

We started out in Rosslyn, a suburban neighbourhood in the north of the city host to the Nairobi Contemporary Art Institute (NCAI) and One Off Gallery. NCAI is a recently opened white-cube non-profit gallery on the top floor of Rosslyn Riviera Mall, while the traditionally commercial One Off has occupied its rambling property and gardens since 1994. Both locations couldn’t be more different, but their occupants both serve a vital function in providing Kenyan artists space and support to formally exhibit their work.

Later on, we returned to Kilimani to visit the GoDown Arts Centre and Kuona Centre for the Visual Arts. Both destinations represent their respective collectives by providing their artists with studio space alongside each other, creating a centralised and communal place to work and engage with the wider community.

Everyone we met was welcoming and engaging, interested not only in our work but what it was like, as Jamaicans, to visit. Unlike Kingston, Nairobi seemed to have more collectives, mentorships and space – so, so much space. Being in Kenya crystallised for us what’s missing in our society.

Yet, Kenyans and Jamaicans are both untangling their complicated colonial inheritances while navigating the pressures of neo-imperialism. They also both recognise the cost of ‘development’ is far too high – but exploitative debt means the countries have to pay it anyway.

“Rather than relying on the Western model of ‘advancement’, this tradition of collectivism supports these Kenyans in their aspirations for the future”

Still, in Nairobi, I got the sense that there are ways to push past these imposed restraints. The artists and administrators I spoke to shared a common desire to address scarcity through community. Rather than relying on the Western model of ‘advancement’, this tradition of collectivism supports these Kenyans in their aspirations for the future.

Those three weeks in Nairobi may not have taught me what I went there to learn, but the more time I spent there, the more I understood the city I was from and what I wanted to see in my own country. For me, the most expansive lesson Nairobi had to teach me was that another world is possible.

Highlights:

- Cheche Bookshop and Café is an independent Pan-African feminist bookseller in Lavington. They host community events, which they announce on their Instagram.

- Karura Forest: Several nature trails and bike paths take you through a gorgeous upland forest reserve, where around 40% of the trees are indigenous. It also smells incredible.

- Every night out will end up at the Alchemist sooner or later, but it’s also a cool destination when the sun is still up.

- As a dedicated non-profit art gallery, NCAI is the first of its kind in Nairobi. Apart from the exhibition space, they also have a library with a beautiful view of Rosslyn.

- Alongside Unseen Nairobi’s independent cinema is their rooftop bar and café, which offers a fantastic view of the city.

Useful Info:

- The traffic in Nairobi really is murder. If you need to travel during peak hours, which are about 6 am–10 am and 4.30 pm–7.30 pm, factor in a delay of at least another hour.

- If you’re in Kenya for an extended period, it may help to buy a SIM card and download the MPESA mobile money app. Mostly everyone uses it, from street vendors to taxi drivers to upscale restaurants.

- Be careful taking photos in the city as it is illegal to photograph government buildings in Kenya.

Like what you’re reading? Our groundbreaking journalism relies on the crucial support of a community of gal-dem members. We would not be able to continue to hold truth to power in this industry without them, and you can support us from £5 per month – less than a weekly coffee.

Our members get exclusive access to events, discounts from independent brands, newsletters from our editors, quarterly gifts, print magazines, and so much more!