image by Christiano Betta

Trigger warning: mentions of sexual assault

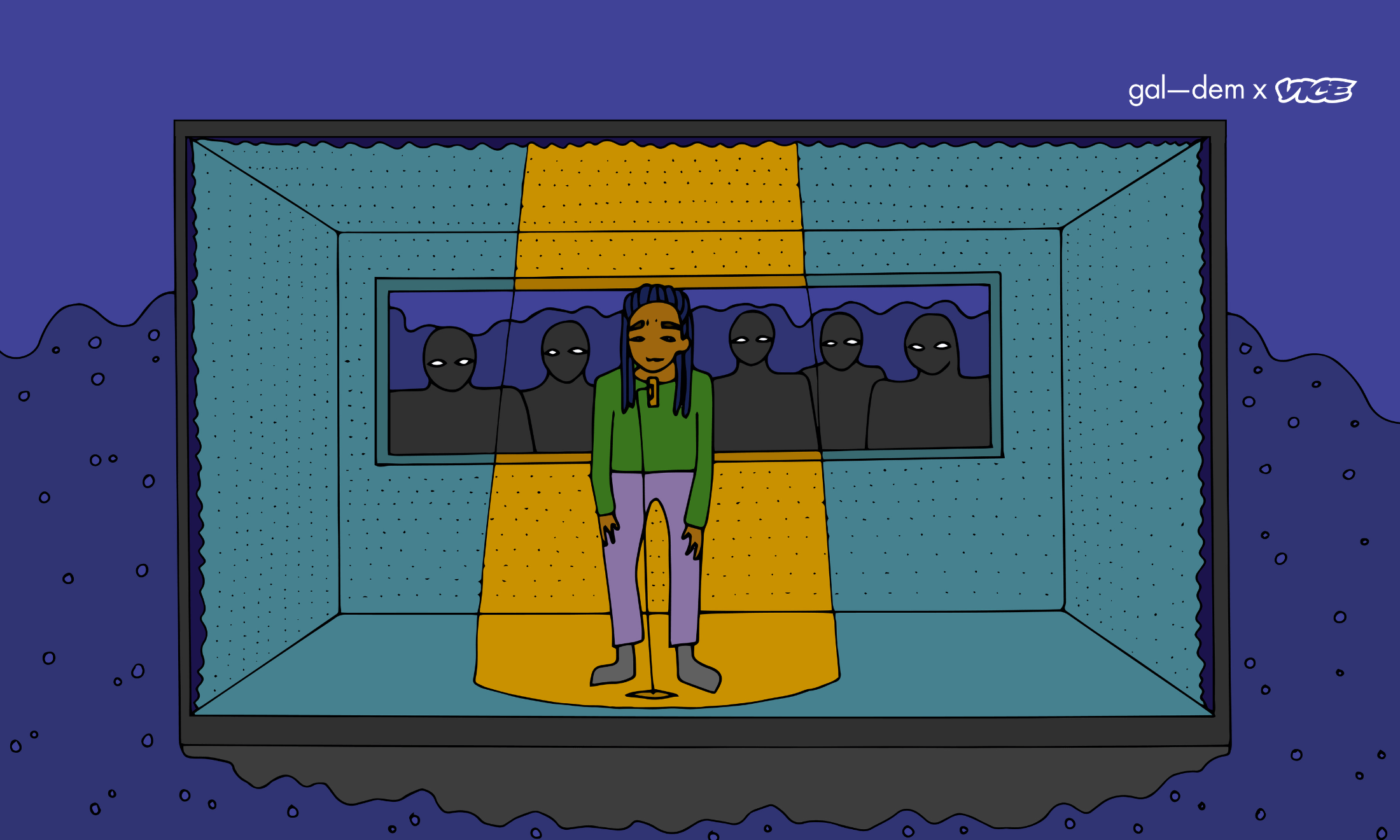

Why is it that an event vital for the education and appreciation of Caribbean and diasporic identity now involves a problematic issue that few people are talking about? Why, as women, do we expect to be sexually harassed at carnival? Or, more worryingly, why is it being normalised to the point where we don’t question it? It isn’t widely reported, and apart from threads on Twitter, there’s little to no commentary in the mass media. However, for myself, a central reason for not attending this year’s carnival was simply because I didn’t want to be sexually harassed and perpetually bothered by men.

Personally, I can’t count the number of times I’ve attended carnival and myself or my friends have been grabbed by men we’ve never met, physically pulling us to dance, trying to kiss us or worse. Or the times someone’s touched my bum, or even picked me up and carried me off. I also remember one year when someone managed to violently grab my crotch area and run off before I could even react. These are some of the few experiences of sexual harassment and assault that many women will attest to having experienced. And yet, somehow, we’re so desensitised with this behaviour that some men will actually be confused if this harassment isn’t accepted on a day that was originally erected to promote cultural awareness and equality – see the irony?

“Personally, I can’t count the number of times I’ve attended carnival and myself or my friends have been grabbed by men we’ve never met”

Only nine cases of sexual offences were reported at the event this year, yet three women I spoke to who attended carnival and complained of experiencing some form of sexual harassment. Kaitlyn, 21, is a long-time attendee of the carnival and someone who’s used to the lively crowds of the event, but yet she still recalls her shock at being harassed on the streets. “I was dragged by my arm, which was actually quite aggressive,” she tells me. “Someone also grabbed my ass. It’s shocking”. A similar experience was had by Taija, 22, who was dragged from her friends by a stranger in the crowd. “He tried to kiss me on the lips, even though he clearly heard me say no – it was so gross. That’s just one example of many”.

Perhaps the most appalling story was Mia’s, 22, who had a stranger become violent when she told him ‘stop’. “A guy tried to grab me and touch my bum, but my friend was looking at him and told him to stop, saying ‘she has a boyfriend’, but he didn’t. He just got really aggressive towards her, saying ‘I wasn’t talking to you, shut up’. In the end, he had to be physically held back by his friends”. It’s these experiences that show not only the extent of harassment women face at the event but also the common attitudes of men towards women over the carnival weekend.

And yet, in the face of these first-hand experiences, many will try to dismiss this behaviour as simply being “part of the culture”. Being raised by second-generation Jamaican immigrants, I’ve been exposed to Caribbean culture all my life, and as such, the music that makes up so much of both my cultural heritage and identity. From the reggae that became international through the influence of artists such as Bob Marley, branching off from the late 1970s to the 80s and becoming dancehall, creating a distinct culture wherein energetic and vibrant dancing is an integral part of the genre. Dancehall is loud, it’s a genre that commands attention, evident in its worldwide mainstream success and though some take the dancing to the extreme, it shouldn’t be associated with violence or assault against women. So why, on the one weekend celebrating Caribbean culture and its history within the UK, are we making it so?

On the surface, this behaviour is so common now that most view it as being admissible, as simply “boys being boys”, and most women who have been on the receiving end, including me, have usually brushed it off. Perhaps it’s because it’s only a two-day event, that people assume nothing is off limits, and so the underlying issue of harassment is swept under the rug, resulting in the lines being blurred between light-hearted fun and assault year after year. It’s imperative we speak out and talk about this issue simply because if we don’t, no one will.

Mainstream media has prioritised topics like knife crime and arrests at carnival for years to further their own political agenda, such as the 69 who were held “on suspicion of possession of an offensive weapon”, even though the rates of violent crime were actually lower compared to that of last year’s. While the media are fixated on the narrative of black culture correlating with violent crime, it’s neglecting social issues of hyper-sexual behaviour against women at carnival in the process. Because, no matter how hard some will try to suggest that this is the “culture”, or “normal”, the fact is, it’s not. It’s not the norm within Caribbean and African cultures to force women in any situation, and perpetuating that idea is harmful not only to the weekend event but also to our communities.

“When the Windrush generation started Notting Hill Carnival in 1966…they likely had no intention for it to become a hot spot for toxic masculinity”

In my opinion, if any woman was dragged so hard in a club that their arm was bruised, there’d be an immediate retaliation, and if it was brought to social media, there’d be viral condemnation. And yet, for carnival, this harassment acted out predominately by men is becoming much more than just an annoyance, it’s also off-putting. Some women will actually avoid carnival for the simple fact that they don’t want to be bothered by men. Rarely can you simply go and enjoy yourself, eat some food, and dance at different sound systems. Now, you have to worry about being groped in the thick crowds, being inappropriately touched, or being directly assaulted.

It’s not only shameful but dangerous to the longevity of the event and its purpose in the current political climate. When the Windrush generation started Notting Hill Carnival in 1966, there was probably no doubt in their minds that it would grow and evolve as the years went by, but they likely had no intention for it to become a hot spot for toxic masculinity. The question is, then, how do we combat an obvious issue that many will brush off as not being “that deep” enough to be an actual problem?

While this article will undoubtedly create a necessary discussion of what is and isn’t acceptable, there has to be a shift in attitudes towards not only the way women are treated but also to the hypersexual atmosphere at carnival overall, if there are to be safe spaces for everyone at the event in the future. Harassment has no place at carnival. The event is a way of keeping culture alive, of educating and preserving diasporic identity in the face of oppression, not alongside it.