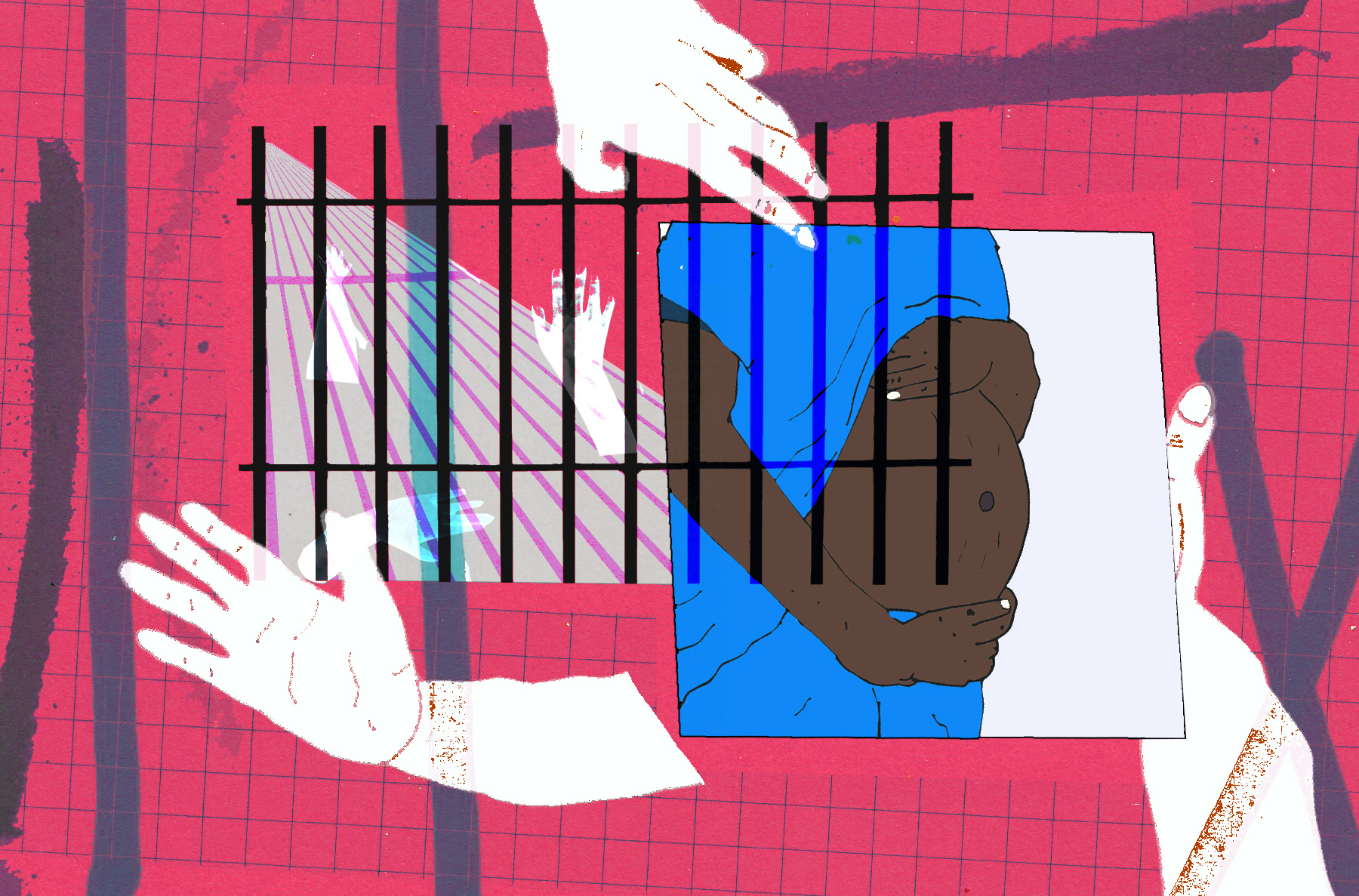

Illustration by Naomi Gennery

What is it like when you’re pregnant in prison?

Forced abortions and sterilisations paired with increased vulnerability to coronavirus: we investigate a system beyond reform.

Nancy B Uddin

25 Jun 2020

TW: descriptions of sexual assault and violence

All eyes are on America’s justice system right now. As police abolition becomes a mainstream conversation, we’re reminded of the unique experience of prisoners too. The United States has 4% of the world’s population of women but 30% of it’s incarcerated women’s population.

While 231,000 women are reported to be imprisoned or detained in jail facilities, state prisons, federal prisons, immigration detention facilities, and more, there is scant official data on the number of non-binary, trans, genderfluid, and intersex population that are incarcerated—all of whom need reproductive health access. Most people who give birth while incarcerated have to hand their baby over to a family member or friend. This is just one of the stressful choices pregnant people face while incarcerated. However, the jail system systematically attempts to remove women and non-binary inmates’ agency over their own bodies.

The US is responsible for around a third of the global women’s prison population. Inequality is inherent in the experience of incarceration from the outset; black and indigenous women are disproportionately represented in prisons and jails, meaning that prisons exist as a microcosm of the country’s dehumanising treatment of people who are already marginalised. Add to this the experience of being pregnant, or being somebody who could fall pregnant and there’s a myriad of issues you can’t control. Solitary confinement, medical negligence, forced sterilisation, and sexual assault combine to compound staggering reproductive injustice in prisons.

Horrifying stories have recently come to light. In September 2019, a woman gave birth unsupervised in Britain’s largest women’s prison, resulting in the death of her baby. A UK government report details accounts of people miscarrying while wearing handcuffs, and in North Carolina, incarcerated pregnant people routinely give birth in solitary confinement. During the Covid-19 crisis, it has been found that pregnant people are more at risk, yet they still languish in cells. In late April, Andra Circle Bear, a Native American woman, died in prison in Fort Worth, TX after giving birth on a ventilator one month earlier. She was serving a short two year sentence for a minor drug charge. Around the same time, NY Daily News reported that lawyers at The Legal Aid Society wrote a letter to the Department of Corrections and Community Supervision acting commissioner Anthony Annucci demanding that 10 pregnant women be released from Bedford Hills Correctional Facility. As of last month over half of them were still there.

There are no mandatory standards of care for pregnant people in U.S. prisons. Although the discussion around reproductive justice has increased, people in prison are rendered invisible in the face of the crisis over reproductive justice at large in America. “I don’t see how there can be reproductive justice for the masses when so many people are in cages and their experiences are left out of the greater conversations,” said Alexia Arocha-Bergquist, a former Legal Advocacy Coordinator at Justice Now. The reproductive rights movement needs to actively advocate for reproductive justice for all, including those behind bars.

Researchers from the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine say almost 1,400 pregnant women were admitted to 22 U.S. state and federal prisons in 2016;the rate of increase of women in custody has surpassed that of men.

Coerced, punished and traumatized

Incarcerating women can break up family units and lead to mental illness and sterilisation for those directly impacted. They can be shackled during childbirth as seen first hand by Dr Carolyn Sufrin, an assistant professor of gynecology and obstetrics at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. They can have their complaints of contractions, bleeding, and labour ignored, and deliver babies in their jail cells or prison cells.

“The prison staff tried to force me to terminate [my] pregnancy, claiming that as a ward of the state, I had no choice,” says Laura Berry, a previously incarcerated person, in a Buzzfeed article. “But I refused and was put into solitary confinement for lying about who had fathered the child, and for having had ‘consensual’ sex with an officer. In solitary, I had no mattress and was fed only bologna sandwiches.”

In many cases, the trauma of pregnancy in prison is longstanding. “I’m laying there, I’m bleeding, I’m shackled to a bed, I’ve got these two men down between my legs that I don’t know from Adam, and they’re there saying that they threw my baby in the trash,” Pamela Winn, a formerly incarcerated woman, told The Independent of the moment. “It’s not something I will ever forget. Ever.”

“The prison staff tried to force me to terminate [my] pregnancy, claiming that as a ward of the state, I had no choice”

Imprisoned pregnant people are at the will of the prison and many times punished for self-advocating. “Even if one of the [women] had intercourse with an officer and became pregnant [with or without consent], the abortion would be denied,” says Crystal Chisholm, a formerly incarcerated individual and a client of Operation New Hope, an organisation that supports people get skills for a job post-incarceration. “Normally if there was an issue with an officer, the [women] would end up in confinement.”

Prisons also have a prevailing history of coerced sterilisation onto imprisoned people. “Incarcerated people who have marginalised identities, or populations who are deemed ‘undesirable’ were disproportionately being coerced into sterilisation,” says Hanâ Zait, a former Legal Advocate at Justice Now. “Based on the history of eugenics [in the United States], there are certain groups of people that the state doesn’t want to have reproductive agency.”

Buck v. Bell, the court case which reversed the compulsory sterilisation of those committed in state institutions, has yet to be reversed by the United States Supreme Court. State senators in California introduced Senate Bill 1135 in 2014 to prevent coercive sterilisation unless medically necessary for the individual. Not only is the bill overdue, but it is indicative of how poor the human rights abuses inside the institutions must be nationwide. In 2013, the Center for Investigative Reporting found that at least 148 people that are registered as a female in California received tubal ligations without their consent between 2006 and 2010.

“Rather than solely focusing on the right to not give birth to a child, we should be having a larger conversation about the right to choose whether or not to have a child, when to have that child, and the ability to raise that child in a safe environment,” says Zait. “People in prison are routinely denied rights, be it folks who wanted to have kids but were coercively sterilised, or folks who may already be caregivers but are forcibly ripped away from their children through incarceration.”

What should happen vs what really happens

If no one can help, then the baby goes to the Office of Children’s Services. In some states, there has been a push to create prison nurseries that allow women to keep their newborn children with them, behind bars, where they can stay with their mothers until the child is 18 months or 2-years-old.

For Riker’s Island in New York City, admission to the nursery is determined by the Department of Correction and Administration for Children’s Services review, outlines Jennine Ventura, the Director of Communications and Public Affairs for Correctional Health Services. It is based on the best interest of the child and must be in accordance with section 611 of New York state correction law. The nursery is a space for expectant mothers to live together. There are baby beds available and infants can stay in the nursery until the age of 1. Prenatal or postnatal care, mother/child residences, substance use treatment programs, and other social services are also provided. Mental health services for postnatal depression are available and termination of pregnancy services are offered through Elmhurst Hospital.

Although this is the policy written on paper and several courts have held that incarcerated women have the right to an abortion, many women are not able to get them. Incarcerated people are impeded from learning about their rights. Although there is a Prison Library, officers have the autonomy to decide what information to disperse, according to Chisholm. Sheriffs also refuse to pay for the transportation costs or monitoring, which is added to the cost of the abortion and totals tens of thousands of dollars. While some pregnant incarcerated people are not aware that abortions are even a legal option, others who are pregnant and jailed are still deterred from seeking abortions. Corrections staff may ignore and obstruct the request.

“People in prison are routinely denied rights, be it folks who wanted to have kids but were coercively sterilised, or folks who may already be caregivers but are forcibly ripped away from their children through incarceration.”

A system beyond reform

Abolition is the only solution. The prison abolition movement demands structural transformations to navigate violence and crime in this country and is supported by organisations such as Justice Now, Critical Resistance, and INCITE!. Justice Now provides direct legal services to people throughout the state of California. Critical Resistance is a grassroots organisation that works to build a mass movement to dismantle the prison-industrial complex. INCITE! is a network of radical feminists of colour organizing to end state violence. The abolition movement stems from abolitionist activism that ended slavery. Based on transformative justice, love, and intersectionality, abolition pushes us to understand layers of oppression and challenge systemic causes of oppression.

“From the lens of abolition one sees how everything intersects and it is imperative to see the intersections in order to move forward in protecting reproductive rights for all,” says Arocha-Bergquist.

By using abolition as a strategy, people can still tackle reproductive injustices by taking concrete steps such as donating to local grassroots organisations, such as National Network of Abortion Funds (a network of more than 80 funds in at least 38 states that seeks to eliminate economic barriers for low-income individuals seeking an abortion), volunteering as a clinic escort, facilitating workshops that discuss reproductive rights, and calling Congress to vocalise opinions.

It is also important to self educate about the racial implications of the “war on drugs” and the ways in which low-income communities of colour are targeted by law enforcement and harmed by current drug policies. We should have critical conversations (while prioritising our energies) about mass incarceration and reproductive justice and challenge language that reduces folks and brands them solely as criminals (i.e. calling people inside inmates, prisoners, etc.). These conversations have the potential to normalise abortions and destigmatise people practising self-agency over their bodies.

Reproductive justice for everyone is an urgent issue because reproductive rights are being attacked now; our activism can serve as a stepping stone towards accountability. We are even seeing victories, including after an ongoing silent protest against the multiple accounts of mental and physical abuse in Lowell Correctional Institute, Florida Department of Law Enforcement will be leading an investigation. “We want to share with the world that we are not just a number,” says Chisholm. Our participation in the resistance towards carceral injustice and reproductive injustice is paramount.

“I think it’s important to think about repurposing prisons and not only in the way that we incarcerate but by retraining and rehabilitating,” says Amanda Mahan, the Marketing Specialist at Operation New Hope. These tactics can have positive impacts with ripple effects on real lives, from a reunited family to a child delivered in comfort.

Whatever a world without police or prisons looks like has to be something dramatically different from the dehumanising behemoth that exists right now.

Britain’s policing was built on racism. Abolition is unavoidable

How Pakistan’s Khwaja Sira and transgender communities are fearing and fighting for their futures

Their anti-rape performance went viral globally. Now what?