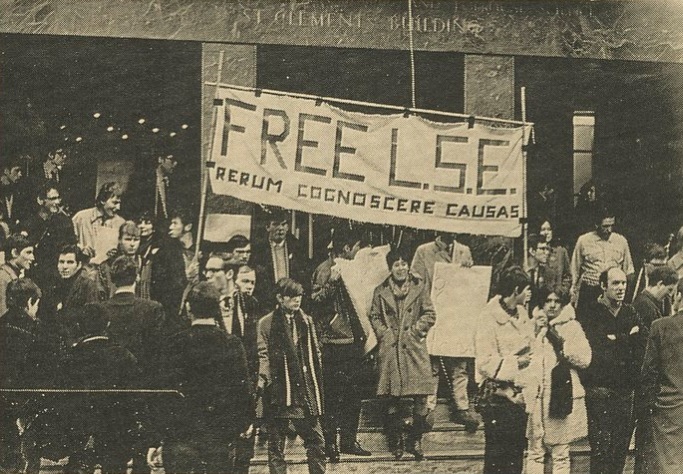

Students holding a banner reading “Free LSE rerum cognoscere causas” outside St Clement’s Building / Photography via the Beaver, 1966

Universities are intense hotbeds of activism. Students have time, energy, and are often undergoing their first major political awakenings as adults. Last year saw high profile anti-racist action take place at academic institutions across the country.

First, there was the Goldsmiths Anti-Racist Action (GARA) in March 2019, led by students of colour. They successfully occupied Deptford Town Hall – the campus building with the most loaded colonial history – for 137 days, with demands that included the reintroduction of scholarships for Palestinian students and a commitment to tackle racism across the university. Then in November, students of colour at Warwick University occupied their Student’s Union (SU) after a series of protests and petitions against the speaking invitation extended to retired Colonel Eyal Dror of the Israeli Defence Force. They had similar demands, including an investigation into institutional racism in the Student’s Union. But these movements don’t stand alone in history – there is a long and storied history of students struggling for social justice that stretches back to the 1960s.

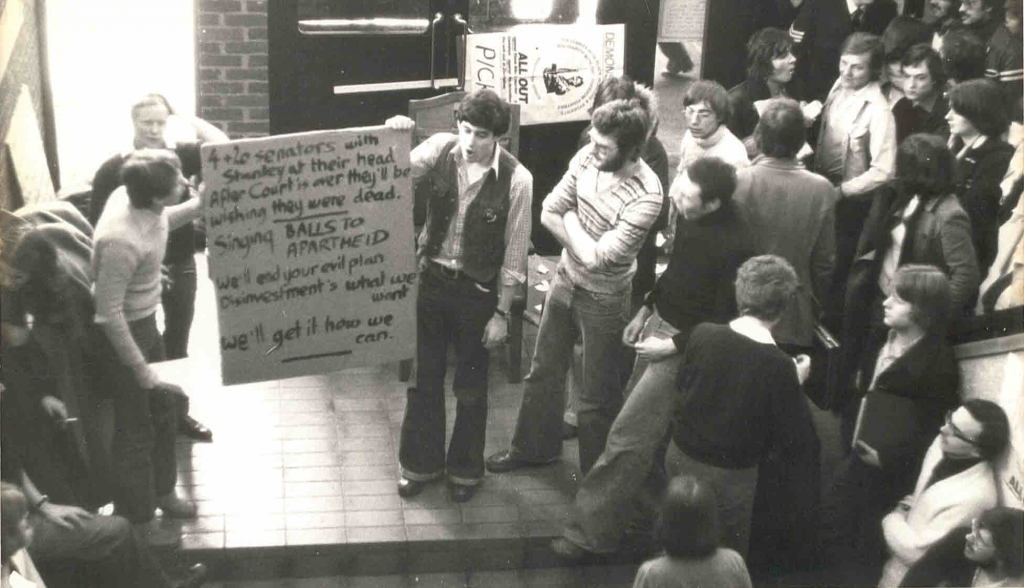

Between 1967 and 1969, students at the London School of Economics (LSE) occupied several university buildings in opposition to the appointment of Walter Adams as Director of LSE. This was the first high profile student occupation in the UK, making national headlines at the time. Walter had served as the principal of the University College of Rhodesia, and so his appointment sparked questions such as LSE’s complicity to the apartheid regime and its support of Rhodesia, and the role of students in influencing the appointment of LSE Directors. At the peak of protests in 1969, 40% of students were involved. LSE was closed for 25 days, as some activists broke down the steel gates with pickaxes. Adams remained director of LSE until 1974, but the protests ensured significant improvements in the student experience at LSE.

“There is a long and storied history of students struggling for social justice that stretches back to the 1960s”

Student action like this was widespread across the UK, with students challenging universities directly, or leveraging their voices to bolster national and international movements such as the Miner’s Strike 1984-85 and various anti-racist demonstrations such as the Printworkers strike.

“I don’t think there was a struggle we weren’t part of,” recalls Director of War on Want Asad Rehman, reflecting on his experience as a student at the University of Essex in the 1980s. “You looked on television and you saw what was going on with the Israeli invasion of Lebanon, the massacres in Soweto and they all mattered to you. Nicaragua mattered to you. No matter where you looked, we [people of colour] were being killed.” Asad joined the Black Students Alliance which was a radical political group at the University of Essex dedicated to fighting against racism and imperialism.

During his time as a student, the group successfully campaigned for an anti-racism officer post in their SU, a scholarship for a member of the African National Congress and a Palestinian student against raising tuition fees and the prevalence of the National Front’s “Rights for Whites” movement in Essex.

Each generation of activists looks to previous generations of movements not only as a source of inspiration but for solidarity and strength in networks. As in the 1960s and 1980s, the aims of occupation movements are similar, often revolving around the prevalence of racism at institutions. But given different contexts, decisions to occupy or use other forms of protests vary. “Surrounding issues of Palestine, part of the fight was socialising people into understanding, so we had to win motions, create art to make sure we win the cultural war,” Asad says of his student activism.

Years later, the 2019 Warwick Occupy action decided that cultural touchpoints alone would not sufficiently capture the urgency of making their SU recognise their racism, so instead turned to occupation. Nazifa Zaman, a second-year student and occupier explains: “Out of anger and hurt we marched to the SU offices, and after seeing how little they care, it did infuriate us.”

“At the peak of protests in 1969, 40% of students were involved. LSE was closed for 25 days, as some activists broke down the steel gates with pickaxes”

But this action comes with a price; the prevalence of violence as a response by the universities is a regular feature in student movements, especially in occupations. During the 1967-1969 LSE protests, policemen were called to guard the entrances to the university and arrested 30 students.

Fifty years later, during GARA’s occupation of Deptford Town Hall, Hafsa Haji, a Politics and International relations student at Goldsmiths University recounts how occupiers were labelled as “aggressive” and external security was hired, with the ratio of security guards to students being about 4:1. “Anytime someone ventured out, there would be a massive presence of security guards and we really felt cornered. It took one of our Sabbatical officers, who was concerned about our wellbeing, making a call to the Estates Team to give us access to exits,” she says.

This militant response to student activism transcends the UK. It was also dominant in South Africa’s “Rhodes Must Fall” campaigns in 2015, where police dispersed protesters with stun grenades and rubber bullets, and at John Hopkins University in the United States where seven people were arrested during an occupation against campus police contracts being given to the US Immigration and Customs Enforcement Agency (ICE) in 2019.

For student movements, especially those led by people of colour that address issues of racism, violence is not the only problem they face. From the planning of an occupation and its implementation, the question of how white allies should be involved in these movements is a common theme.

For Asad, in the 1980s, cultivating the Black Students Alliance as a space away from traditional left student organisations which were predominantly white was important in shaping his radical identity. In Warwick Occupy, Akosua Sefah, a student at Warwick University highlights the decline of white allies as the occupation went on. “We did notice that we had less white allies with us in the occupation, especially getting towards the holidays, but they were important when it came to talking to security and remaining in the space whilst we were away at negotiations with the SU.”

“From the planning of an occupation and its implementation, the question of how white allies should be involved in these movements is a common theme”

However, in student movements more broadly, the hypervisibility of students of colour can be uncomfortable. Carl Gomes, who was involved in an occupation surrounding the closure of arts courses while studying at Surrey University in May 2019, recounts feeling frustration during meetings in which ethnicity was stressed. “Asking ‘why do we not have enough people of colour/LGBT/female etc … students?’ terminated plans that could have done real, tangible good for the student body,” he says. “The most difficult thing was trying to understand just what ‘enough’ meant in these circumstances: what is enough non-white involvement? Why was it sometimes not enough for all of the POC members to want to partake in an activity?” These questions illustrate the issues of the co-option of intersectionality and solidarity at the surface level in student movements.

Past and current student movements have not ended their fight after the success of an occupation but continue to negotiate with and put pressure on their respective institutional bodies in regard to their demands, particularly with GARA and Warwick Occupy. They have also collaborated with other student movements across the country and internationally, such as GARA getting advice from previous student occupiers and students at John Hopkins University. This allows for the pooling of resources and knowledge – like legal counsel – that is crucial to the success of occupations.

The support of institutions such as the National Union of Students (NUS) is also essential. Hafsa explained the importance of advice GARA got from students in the NUS. Historically, the NUS organised campaigns such as the 1973 defence of education grants, which called for the increase of student grants and the reduction of rent and food prices. Around 400,000 students joined the campaign, resulting in a 25% increase in student grants. This shows the impact that the NUS can have on student politics, and why Asad campaigned to have greater black visibility in the NUS during the 1980s.

However, more recently, the NUS’ power has waned. Al-Hussein Abutaleb, a member of the Sheffield Occupation in 2009 in solidarity with the people of Gaza, said he would like to see more students of colour involved in the NUS as, over time, confidence in the organisation’s ability to place pressure on universities has eroded. The NUS is currently facing structural and financial difficulties and so cannot offer effective support to these movements.

When looking to the future, the direct impact of student movements on policy change in higher education institutions and on wider socio-economic policies is significant. For many activists, organising at university provides them with practical hands-on training on how to oppose and navigate powerful state systems in society. And with issues such as climate change, the voices of students of colour are crucial in situating it within a wider global anti-imperial struggle. It is clear that the persistence of student movements throughout the years has resulted in important institutional change due to the creativity and dedication of student activists.