White Pearl’s ambitious dark comedy requires more critique to work as a satire on racism

Wei Ming Kam

03 Jun 2019

Photography by Helen Murray

The reaction I have to the last scene of White Pearl, Anchuli Felicia King’s international debut play, is possibly the most visceral one I’ve had yet in a theatre. Five of the main characters, all East or South East Asian women, are throwing slurs from their various languages with relish at Priya, their Indian-Singaporean boss, and also (to a lesser extent) at each other. When I realise what’s happening, I curl up on my seat in horror and almost fall off onto my partner sitting next to me, and so almost miss the very end. Priya, not understanding any of the racial slurs being said, asks the others, “Why is this funny?”, and when she repeats the question, every actor on stage looks out at the audience. The lights go down.

I clap along with the rest of the audience, and then turn to my partner. “That last scene – what the fuck?”

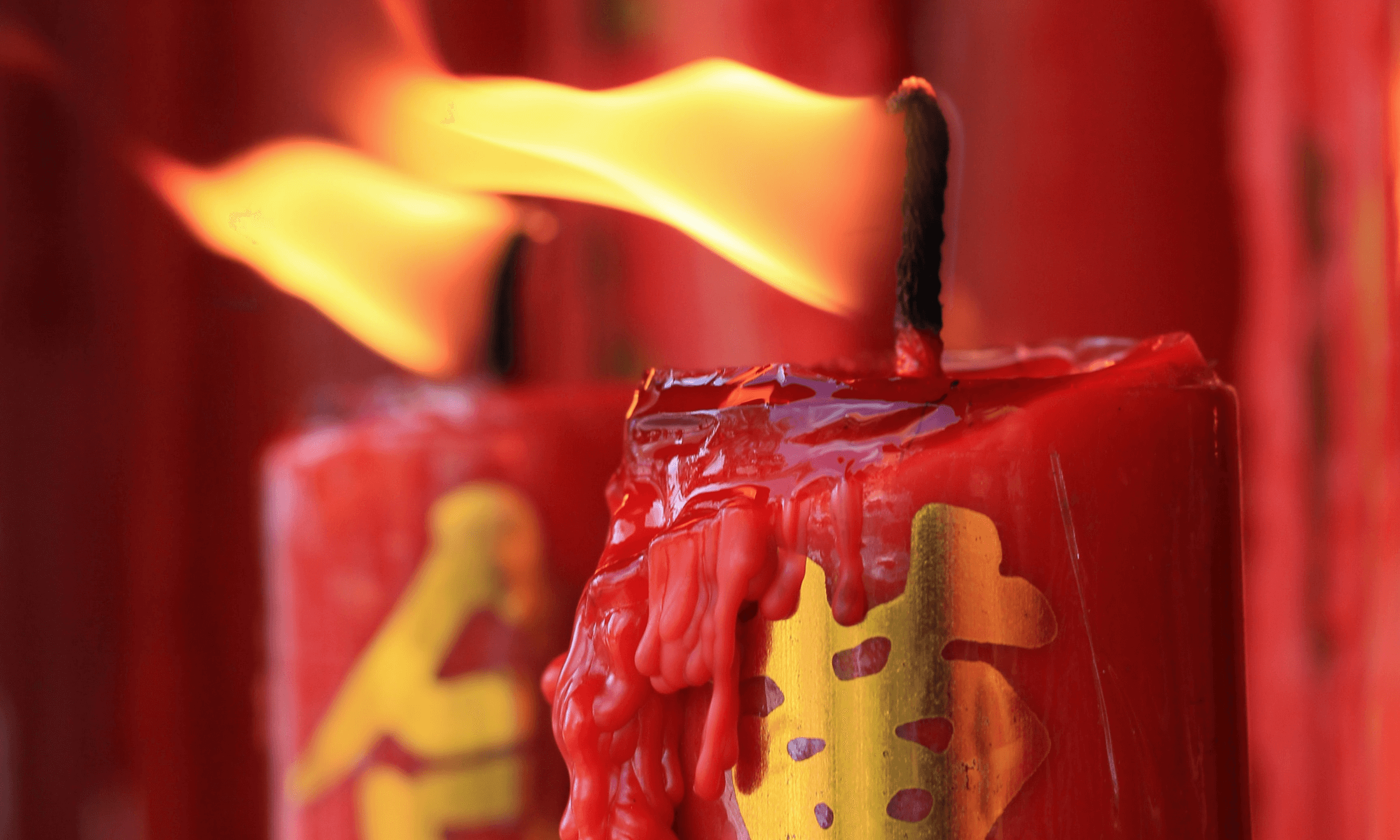

When Felicia King’s play was announced as part of the Royal Court’s 2019 season, there was excitement from British East and South East Asians, who are used to token and/or offensively stereotyped characters in plays. There was also anticipation for how Felicia King would deal with the issues raised by the narrative – including anti-blackness in Asian communities, class, and colourism – that are almost never discussed in British theatre. The plot is kickstarted by an anti-black ad for skin whitening products inadvertently leaked on to YouTube, leading to a very bad day at the Clearday cosmetics office for the six women of the play, and it’s billed as a dark satire on racism and globalized corporate culture in Singapore.

“It is a huge pleasure to see six women from different Asian backgrounds on the main stage in a very ambitious debut from a young, Thai-Australian woman”

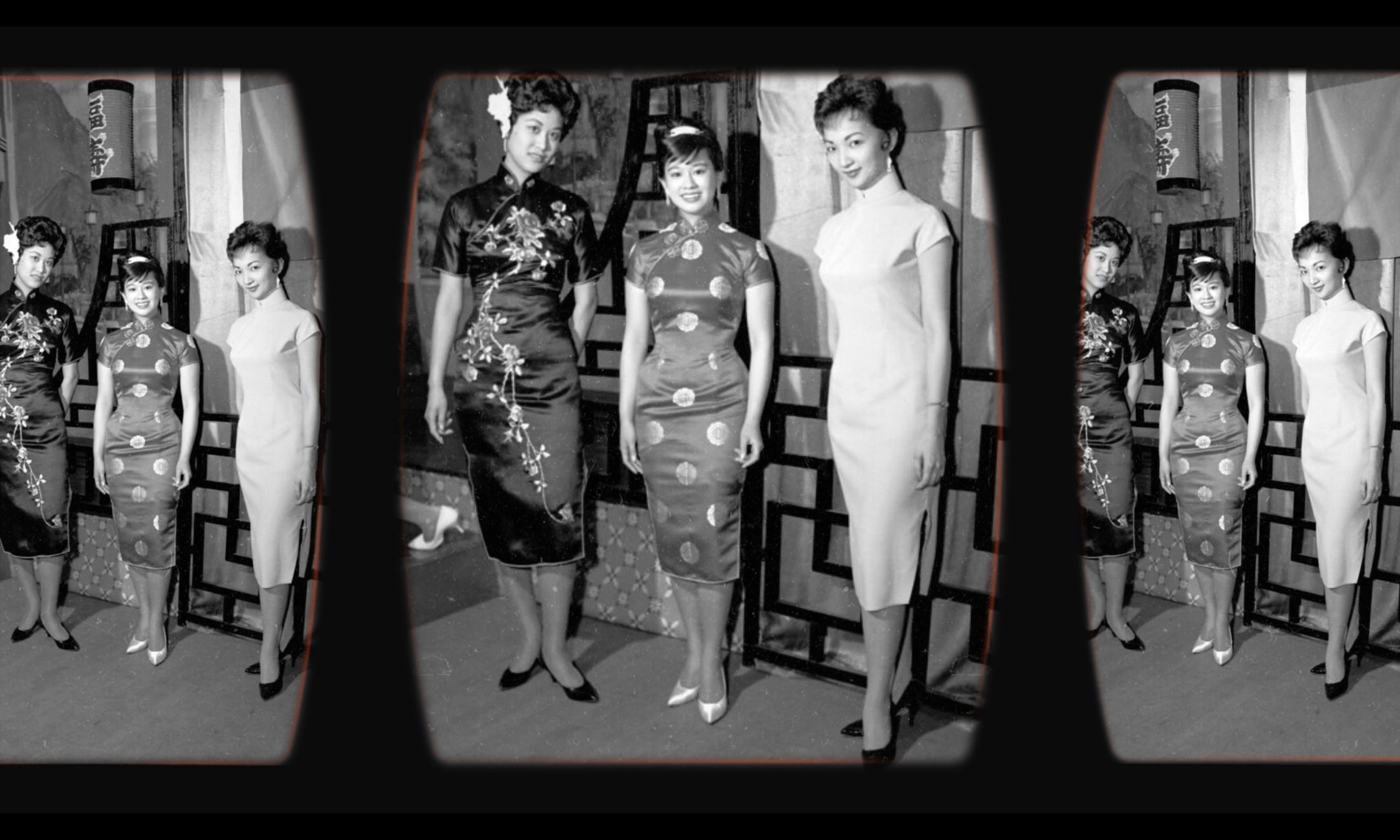

I left the theatre after watching it not convinced that White Pearl fully worked as a satire, and confused on what Felicia King’s purpose was in writing it, and who she was writing for – sentiments echoed in the Asian discussion group I help facilitate at the Royal Court Theatre two weeks later. There’s much to enjoy: the dialogue is energetic and interactions between the characters are sharply observed, the cast have a great time with the script, and the set design and costuming – blankly sleek and illuminating, respectively – are wonderful. It is a huge pleasure to see six women from different Asian backgrounds on the main stage in a very ambitious debut from a young, Thai-Australian woman.

The sly send-up of startup culture is where the satire succeeds the most – Felicia King has a keen eye for the faux-ethical, casual facade that rapidly disintegrates in the face of capitalism’s demands, and the behaviour that accompanies it.

Less successful is the satire of racism in Asian countries. Anti-blackness in Asia is examined all too briefly in a few scenes, and it’s clear that the main focus is on intra-Asian commonalities, differences, and prejudices, but the characters are introduced as lightly sketched stereotypes, and Felicia King has little interest in subverting them or digging deeper. The Japanese office manager Ruki, for example, is sweet, polite, hesitant to speak up, and stays that way for almost the whole play.

Interviews with Felicia King shed some light on her ambitions for this play. In Time Out she said that, “I find that [the characters aren’t sympathetic] really empowering – I have never to my knowledge seen dislikeable Asian female characters… Asian women deserve to get to play something other than caring, inherently likeable, passive characters.” I sympathise with the frustration of seeing roles for Asian women where they are nothing but stereotypes, but question whether aspiring to write Asian women as awful people is empowering. What exactly about this is empowering?

Despite her assertion that she “write[s] for a young Asian woman”, this particular rejection of racial categorisation is still a reaction to the white gaze and one that isn’t, in White Pearl, entirely successful. Setting up characters as two-dimensional stereotypes and then revealing them to be awful, racist people doesn’t subvert stereotypes, and to me, it isn’t character development either.

“It still feels strange that, for a play about a skin-whitening product company, it only engages with white supremacy superficially”

It’s a play driven more by a multitude of ideas and plot than character, and given the short run time, perhaps it is inevitable that it doesn’t all quite hang together, but it still feels strange that, for a play about a skin-whitening product company, it only engages with white supremacy superficially, and largely focuses on personal racist interactions, rather than structural racism.

There is consensus in the discussion group that the end scene is confusing, abrupt, and very bleak. None of the ideas explored are joined together by it, and if the idea behind breaking the fourth wall with, “Why is this funny?” is to confront the audience with their complicity in laughing at the racism in the play, it’s not only heavy-handed but also too late.

“[My plays are] pessimistic about conditions… you have to recognise the shithole you’re in, in order to climb out,” Felicia King said in her interview with Exeunt Magazine, and it’s probably the most accurate summary of what she intended to do with White Pearl. I’m not sure some of the audience would recognise it – the characters certainly do not. Exposing discrimination and the ills of capitalism in Asia isn’t enough in itself to make White Pearl successful as a satire without more critique, just like exposure to racism and colourism isn’t enough in itself to effect change.

White Pearl is playing at the Royal Court until 15 June