Photography by NXSH

Why 14-year-old girls of colour are dropping out of sports – and how we stop them

It’s thought that by age 14, girls drop out of sport at twice the rate boys do. For girls from ethnic minority backgrounds, the figure is even higher.

Miriam Walker-Khan

15 Aug 2019

Photography by NXSH

When I was in year seven, I realised that rugby was on the boy’s PE syllabus, but not the girl’s. I asked my teacher why, and was told: “girls just don’t play rugby”. But I knew I’d definitely seen a girl playing rugby before.

I happened to be – not out of choice, I might add – a member of the school council at that point, so I attempted to campaign for rugby to be added to the girls’ PE syllabus. I’m not going to pretend I was the Greta Thunberg of the sporting world, I got shut down immediately and the next time I played rugby was at Freshers Week try-outs at university. But even then, I felt like a total outsider because so many of the girls had already played at school.

In the UK, it’s thought that by age 14, girls drop out of sport at two times the rate boys do. For girls from ethnic minority backgrounds, the figure is higher. A Youth Sport Trust and Women in Sport survey from 2017 found that only 8% of girls meet the recommended advice that young people aged 5-18 should do an hour of physical activity every day. The figure for boys is double that.

Whether it’s because of GCSEs and needing to focus on education, getting jobs, starting puberty or simply being bored of sports, the list of what accelerates the dropout rate seems never-ending. For some girls, there’s a perception that sport isn’t cool – that it’s not feminine enough. For some girls, exercising while on your period is a horrific thought. At my secondary school, many girls stopped taking part in PE lessons because they thought it was embarrassing to be seen doing sport, or because they thought boys would find it unattractive. I had a friend who played football growing up, and boys would make comments about her wanting to play football because it was “full of lesbians like her”.

There are probably hundreds more reasons that so many girls drop out of sport around age 14. But when you’re a girl from an ethnic minority background, there’s a whole new complicated set of Venn diagram factors thrown into that mix. Whether it’s due to religion, money issues, lack of representation or ignorant attitudes from people in authority, the sad fact is that there’s probably masses of talent being lost. It’s no secret that if you’re a person of colour in the UK, you’re more likely to be from a low-income background. For many, this makes sport an expensive luxury.

Money matters

Lydia John, 26, is from a single-parent family. She was selected to represent the West Midlands in athletics as a teenager. “My mum didn’t really have the time or facilities to take me [to competitions]. It was about an hour there and back. As a 13-year-old, she was okay with me catching the bus from home to school, but when it came to travelling halfway across the city, she was like ‘nah’,” she tells me.

So Lydia ended up dropping out. She says the cost was a huge barrier too. “My mum couldn’t afford to give me £10 a day to go and play sport. The school I went to was quite a well-to-do school and everyone had two parents. Everyone was of a certain social class.

“If your mum and dad pick you up and provide you with a drink, it’s hard to explain to people ‘I can’t do this activity because my Mum can’t afford the subs or doesn’t have the extra spare cash to do that.’ Working-class ethnic minority children are expected to be adults a lot sooner than their white counterparts. [They] don’t necessarily have time to be children and play sports.”

Black and brown kids being treated like adults from an earlier age was certainly true in my athletics bubble growing up. My best friend, who was from a Jamaican family, had a paper round from the age of 12. She was one of the most talented athletes in the country as a teenager, but she had to work because she didn’t have parents who could provide money for the luxury of sport, which meant she always got lifts with us to competitions around the country.

Anita, 29, from London dropped out of tennis and athletics as a teenager. “My mum used to be a tennis player for Nigeria. She was identified as being a talent so a lot of her costs were covered,” she says. “I’d say I’m from a middle-class background, but tennis is such an elite sport in the UK, that if you’re not upper-middle-class with high-earning parents then it’s really inaccessible. It’s not feasible. Especially when you’re aware that you need to focus on your studies. I grew up being told because I’m black I’d have to work harder than everyone else.”

Hijab bans

When you get past the barrier of cost, for many Muslim girls in the UK there’s a whole new set of issues. Often, worrying what others think of what you’re wearing is amplified if you’re from a Muslim background because it’s perceived to be harder to cover up. On my 11th birthday, I received a phone call from my dad who lived 3000 miles away in Virginia, USA. He wished me happy birthday, and then said, “If you’re still doing athletics, remember you will burn in hell-fire if you wear those Lycra shorts.”

It’s not that my dad didn’t approve of sport. He was a semi-professional footballer himself. But as a parent, he knew that for many Muslim girls, 11 is an age that signifies the end of your childhood. You’re starting secondary school, and maybe puberty around that age. That’s why it’s often when girls start wearing the hijab, and that’s probably why my he thought it was necessary to inform me – believing that he would mitigate the damage of my sin – that I was going to burn in hell now that I was on the cusp of womanhood.

Ezdihar Abdulmula, 25, is a basketball coach and player from Bradford, who successfully campaigned for FIBA, the International Basketball Federation, to lift their hijab ban. In year six, after two years of wearing it in PE lessons, Ezdihar was asked by a PE teacher to take off her hijab. “I said no and he kept asking me. I felt really cornered. He said he was going to take me to the head-teacher,” she says. “I told [him] I’d take it off when I get to the field because I didn’t want to in front of everyone with everyone watching me. It just felt like stripping, you know?”

Although this didn’t stop Ezdihar playing sport, she understands how these conversations can damage confidence. “I know a lot of girls have been put in that situation and stopped playing sports. Sport is the one common language that everyone can speak and celebrate their differences through.” Now, there are more available options for Muslim girls. In 2017 Nike launched its first sport hijab. As well as making it more physically accessible for hijabi girls to take part in sports, it’s also a symbol of belonging within sporting spaces for Muslims.

Tracksuit terrors

But for Muslim girls who don’t wear the hijab, though, there’s still the chance that attitudes of teachers could be the biggest barrier. Sahdya Darr, a 34-year-old social justice campaigner, grew up in Solihull and started secondary school excited to continue playing sport. But when she told her PE teacher she wanted to try out for the hockey team, the teacher told her she couldn’t wear tracksuit bottoms whilst playing.

Sahdya’s dad went into the school to speak to the teacher, explaining why she wore tracksuit bottoms and that it shouldn’t prevent her from being selected for teams. “Funnily enough, after hockey try-outs I found out I’d been selected for the team. But the whole thing changed my attitude towards sport and I never tried out for the netball or rounders teams again,” Sahdya told me.

“I hadn’t started secondary school with a dislike for sports. I came to dislike it because I had been discriminated against, and at that age I didn’t know how to stand up for myself to someone in a position of authority.”

Clothing isn’t the only practical factor Muslim girls have to take into account. It’s things like playing sport on long summer nights when you’re fasting, which may still be new to you anyway, or simply having a space to pray. We had a lot of Somali kids at our athletics club, and my mum bought a massive tent so that they could pray in private, as athletics competitions are often full days in stadiums around the country that you’re unfamiliar with. Before that tent, they would have had to find random changing rooms or parts of the field to pray on.

Watchful eyes

Moving on from religion, body image plays a huge role in the drop-out rate. Teenage girls report much higher body image dissatisfaction than boys, with girls feeling more self-conscious when taking part in physical activities.

There seems to be an unnecessary focus on the bodies of black women in particular. I have friends who often received comments about their bums, while training and competing. These comments were always from grown adults, and it left many of them feeling self-conscious.

Serena Williams’ body is constantly fetishised in the media. In May 2018, she played in the French Open – her first tournament since giving birth in September 2017 – in a black catsuit Nike had designed for her. While it looked incredible, it was also engineered to prevent blood clots forming, which she suffered from while giving birth. But the President of the French Tennis Federation banned the catsuit, telling Tennis magazine, “We have sometimes gone too far. You have to respect the game and the place.”

Nike responded with a tweet reading: “You can take the superhero out of her costume, but you can never take away her superpowers. #justdoit”.

Role models

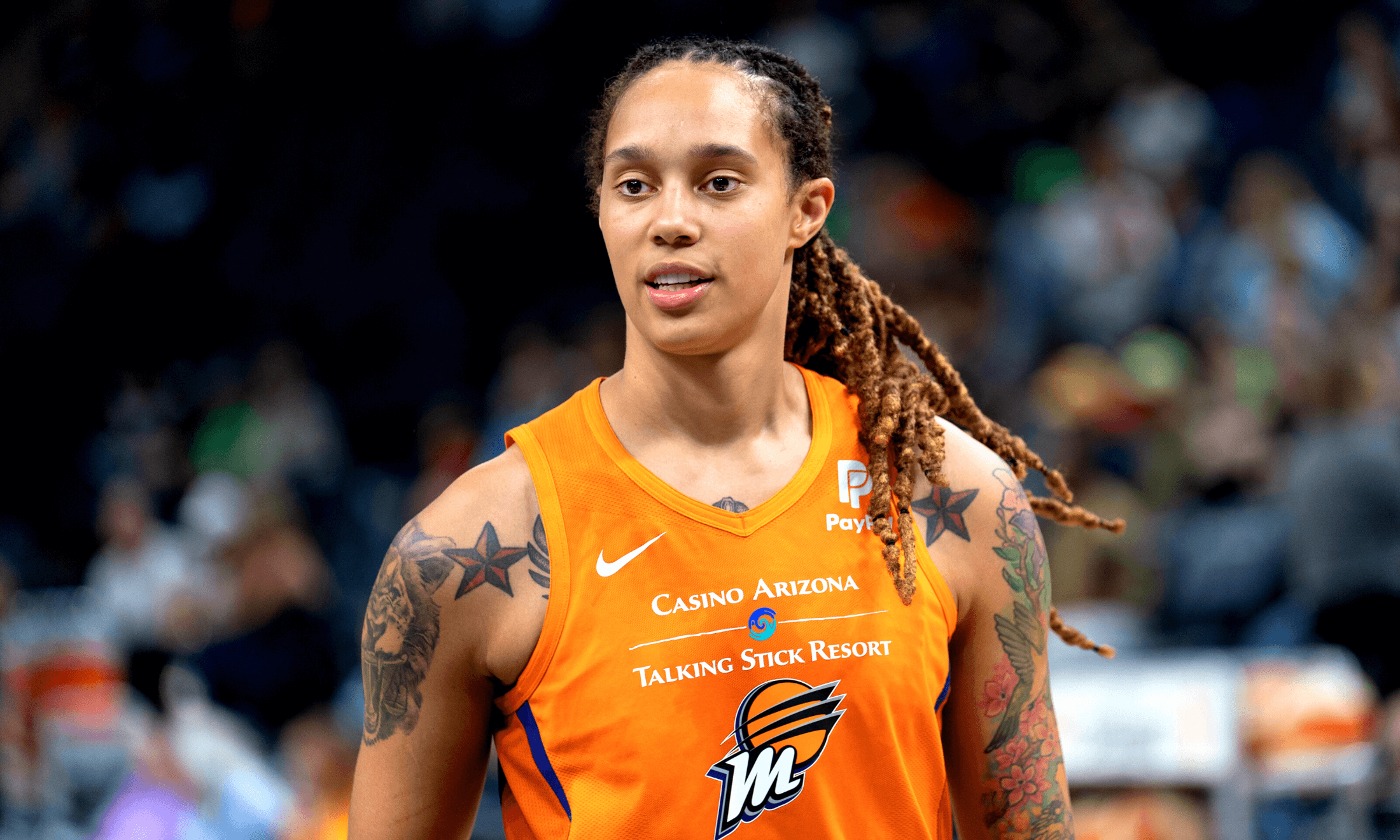

This leads me onto my final point. Role models. I strongly believe that having role models who look like, and are from a similar background to you, is one of the most powerful recruiting tools in sport.

Funke Awoderu is the Senior Inclusion and Diversity Manager at the Football Association, which has a programme focussed on the retention of youth players. “One of its objectives is to identify the most appropriate interventions to keep players participating, particularly important when we consider young girls from BAME backgrounds,” she says. “Role models are also key. We know that BAME girls respond better to people who look like them and aspire to the journey they have taken to get to where they have got in their sporting careers,” she said.

Rimla Akhtar, the first Muslim woman to sit on the FA Council, told me why the lack of role models affects young girls in particular: “I don’t think there are many individuals from black and Asian communities who see girls from their communities having an outlet into sport. We see a lot of black boys going into football at a young age because we see black male role models in the game.”

“Similarly if you saw that with girls, I think you’d see more girls of colour taking part in sport with the potential to take it to the next level.”

Low participation rates for women of colour means less of us volunteering, coaching and in leadership roles. And whatever the reason, the sad fact is that there are probably masses of talent being lost. But if we break the cycle of those barriers and more of us continue to dominate from different backgrounds, we have more role models for future generations of 14-year-olds to look up to.