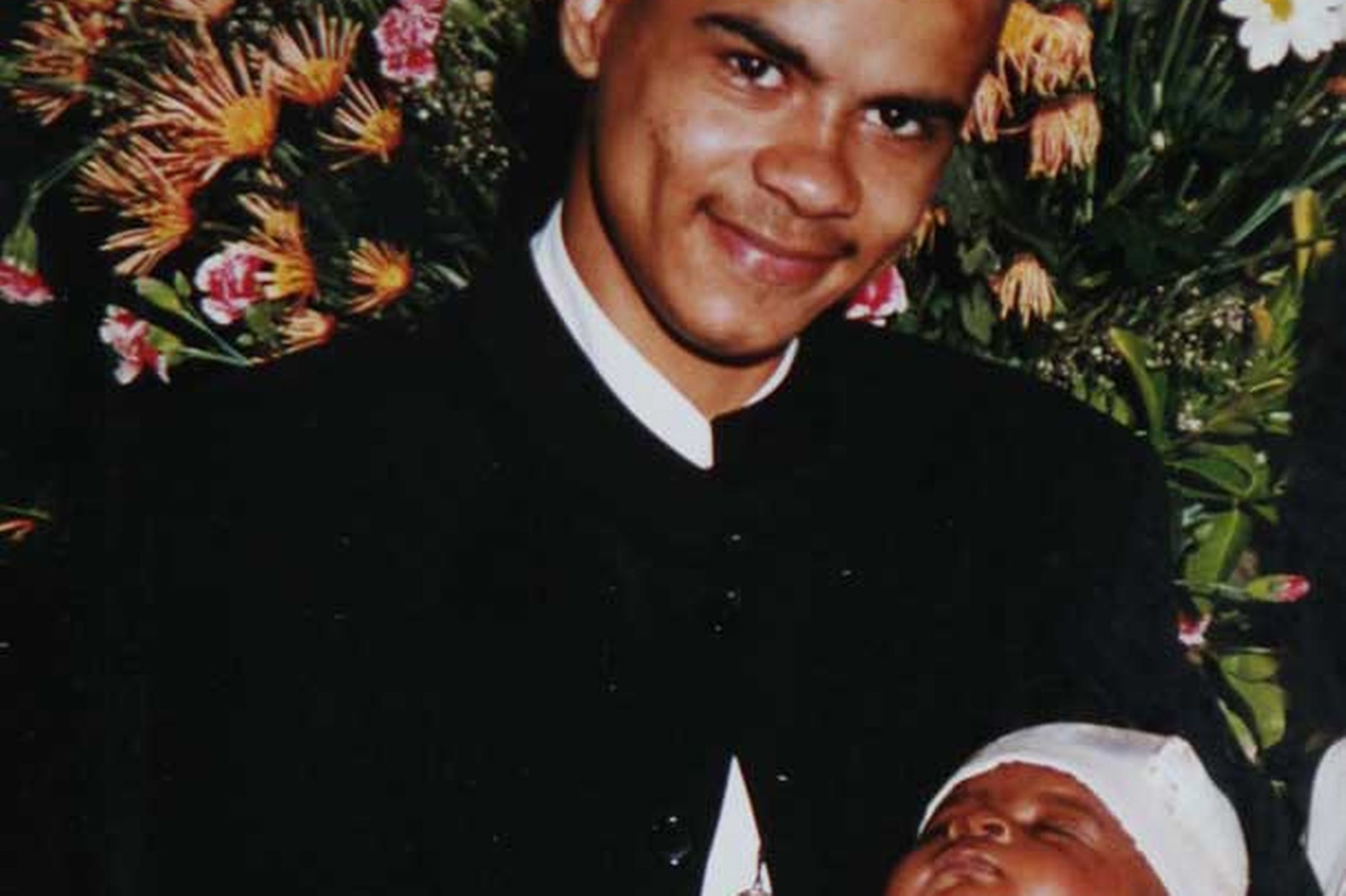

Illustration by Khadija Said

I discovered yoga when I felt my life was about to spiral out of control.

I had given up a job as a newspaper journalist to go freelance but I was terrified of being self-employed. Refreshing my email constantly to see if any pitches had been commissioned was destroying my self-esteem. Sometimes it felt hard to breathe.

One day I walked past a studio in north London and noticed drop-in classes for yoga. I had tried yoga before with some friends at university – we were the obnoxious ones at the back who laughed through corpse pose. But fast forward a decade or so and something about lying still on the floor appealed to me.

Yoga helped me breathe, stroked away the anxiety in my mind. I found a way to move my sluggish body and I began to feel good again. Though I found it a little dramatic, the way some teachers talked trippy and whispered Namaste at the end of a class as though it were a secret spell, I loved the way a class made me feel: the ache after a challenging flow class or the warmth from a candle-lit Yin session. I felt strong physically, mentally. Later yoga saw me through three pregnancies, held my hand through the lonely slowness of early motherhood.

All of this is to say, yoga meant something to me and so this time last year I signed up to a teacher training course. I was drawn to the possibility of both teaching and learning more in philosophical and physical ways. But I was naive.

“This is how cultural appropriation begins: a necklace bearing a sacred symbol here, a Buddha statue for sale in John Lewis for £34.99 there”

It started when we sat cross-legged on bolster cushions for a history class. “Ooh!” one of my fellow students squealed. “Can we learn about Hinduism? I love their gods!” “God yes, that stuff is fascinating,” quipped another, as though we were talking about something on Netflix and not an ancient religion at all. I let it go.

There were other, small things that felt off-kilter. Someone showing off an Om necklace while we waited for a class, another asking the studio manager where she bought the Buddha statue sat upon the table from because – and I quote – “I love Buddha.” Again, I let this go. I told myself I was taking it too seriously.

But this is how cultural appropriation begins: a necklace bearing a sacred symbol here, a Buddha statue for sale in John Lewis for £34.99 there. Cultural appropriation has claws. It snatches things that don’t belong to it, forgetting the truth of it all.

After a session reciting Sanskrit words, I remarked that I felt a little fake doing it. It felt wrong to me, I said, to use Sanskrit in order to sound authentic. One of the women in my (majority white) cohort looked hurt. “I have a Hindu friend. And he says: ‘We Are All Hindu!‘” as if that was that. Another scoffed, told me that there was no room for political correctness in yoga. “If you don’t want to say ‘Namaste’ then don’t say it, love. I don’t have a problem with saying it at all.”

Meanwhile, our yoga teacher nodded patiently. “These are discussions we must have,” she said sagely, only the discussions weren’t had because then there just so happened to be a well-timed break.

“One woman cornered me in tears, shouting that I was ruining our course, bringing nasty things like colour and inclusivity into a place of peace”

I began to learn more about the cultural appropriation of yoga myself if only to work out if I was being over-sensitive because it was not covered in our textbooks and nor was it discussed unless I raised my hand. I learnt that though I felt singled out asking questions about it, I was not alone in my instinct. I realised I was right to question the misuse of a sacred language or of sacred objects. I realised I’d rarely, if ever, seen another brown or black person in a yoga class, let alone teach one. I realised how in the UK, yoga is for a certain crowd. I couldn’t believe I’d never seen it this way before.

I mentioned I felt uneasy by the way yoga was marketed for white, middle-class women and I wondered aloud what could be done to make it more inclusive. Naturally, I upset a few others on my course who told me: “Yoga doesn’t see colour.” It became heated. Another woman cornered me in tears, shouting that I was ruining our course, bringing nasty things like colour and inclusivity into a place of peace.

I walked out of the yoga studio and I did not go back again.

I’m not Hindu. I’m not even Indian. I’m Muslim and of Pakistani heritage but the more I learnt about yoga, the more I realised just how white-washed it is. I gave up my teacher training eight months ago and I haven’t unrolled a yoga mat since.

I know that yoga is hardly the biggest problem facing the world but this stuff troubled me. I realised that if I could feel this way, then how might an Indian person with a tangible connection to yoga through faith, culture or heritage feel? I thought of a friend from school, whose father was a Hindu priest. He would meditate in their small front room with the curtains closed. I wondered how he would feel about yoga being turned into Namastay-in-bed tee shirts and Om necklaces and people dressing up in turbans, mispronouncing prayers they don’t understand.

“It bothers me that trendy yoga studios can make an unknowing mockery of yoga’s origins, such as white teachers adopting Sanskrit names for no apparent reason”

It is not that I believe that yoga should only be for Hindus, or only for Indians, and it is not that I believe that taking a yoga class means you’re doing something inherently wrong; because in its roots, yoga really is meant to be accessible to everyone.

But it bothers me that trendy yoga studios can make an unknowing mockery of yoga’s origins, such as white teachers adopting Sanskrit names for no apparent reason. It bothers me that people can say “Yoga means peace!” as a way of being colourblind and shut important conversations down. It bothers me that when someone turned vicious towards me, no one stepped in to help, no one could look me in the eye. They say you take from yoga what you need. I wonder how much of it might be left when we’re done with it.