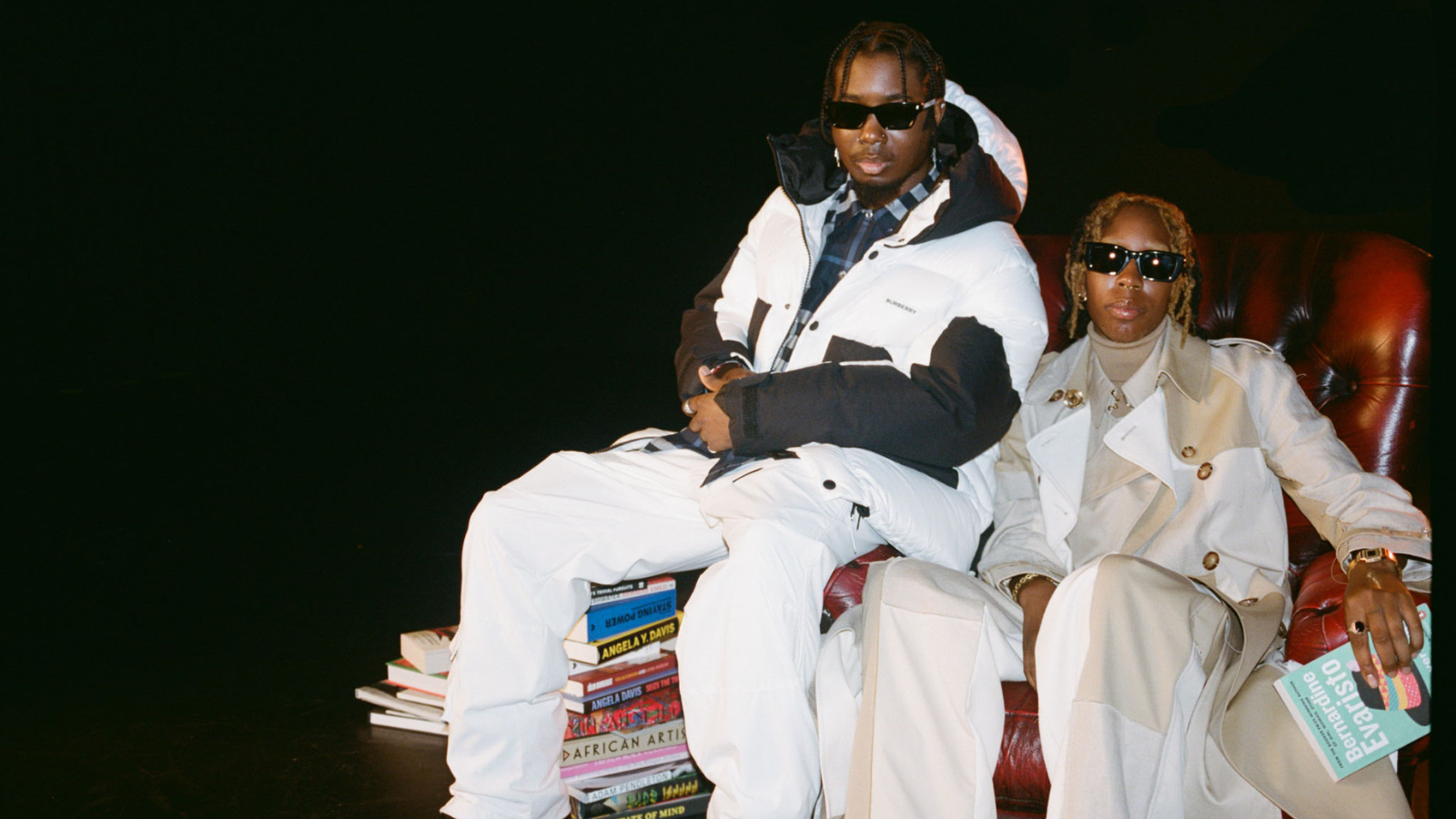

Photography by Kofi Paintsill/Channel 4

This British Black History Month, gal-dem and Channel 4 have collaborated to shine a light on the impact of black British content creators have had on the small screen and scrutinise how far we’ve come in terms of representation. It cannot be denied, the history and contribution of black British people to the television landscape in this country is rich. From Desmond’s, The Real McCoy and the documentary Justice for Joy in the late 80s and early 90s to Babyfather, Comin’ Atcha!, 3-Non Blondes and Little Miss Joycelyn, we have seen a wealth of black talent on British screens. In the last five years, we have been graced with a myriad of series like Chewing Gum, The Javone Prince Show, Famalam, Timewasters, Hood Documentary, Top Boy and documentary series’ like The Black Lesbian’s Handbook, to name a few. After a lull during the early 00s, black British television screenwriters are enjoying a resurgence that promises we won’t return to a time when finding black British representation was like searching for the proverbial needle in the haystack.

For an explanation as to why black British small screen representation has been so hard to come by (as rich as it is, has been and to an extent remains), we need look no further than Channel 4’s 2009 documentary The Event: How Racist Are You? Krishnan Guru-Murthy hosted the hour long experiment by American school teacher Jane Elliott that saw a group of people separated into groups; people with blue eyes were treated as inferior and people with brown eyes were given advantages. The controversial documentary exposed what black British people have always known; British racism is so insidious, so deeply ingrained, that white British people are often more offended by the mere implication of racism than the reality and violence of racism itself.

“British racism is so insidious that white British people are often more offended by the mere implication of racism than the reality and violence of racism itself”

Jane Elliott’s experiment proved that white British people are so uncomfortable with race (other than their own) and racism that they’d prefer to believe that because British racism isn’t as virulent and explicit as let’s say the American Klu Klux Klan that it isn’t a problem. Pearl Jarrett, a black woman taking part in the experiment, explained to her son is was continually stopped and searched by police and that, at the time, black boys were eight times more likely to be stopped and searched by police. Terry Taylor, frustrated by the experiment and its insinuations about privilege, responded: “You keep saying statistics. All kids are stopped and searched by the police. It doesn’t matter what colour they are.” Taylor’s attitude is not uncommon. Black British people often use their own experiences supported by data and statistics as evidence of racism and its effects but rather than honest introspection about racism, many would prefer to continue to uphold the pretence that racism isn’t a problem in modern Britain.

This attitude, the idea that racism doesn’t exist and race is of no concern, has been reflected in British television commissioning. Despite the cultural impact of series in the 90s and early noughties starring mostly black actors, the early 2000s saw a cull in the number of black families and groups on British television. Interviewed in 2012, black British comedian Angie Le Mar explained to the Guardian: “we just can’t get TV networks interested. There really is a lot of racism in the industry: they’re not ready for black women. Commissioners say: “Can you make white people laugh?” Or: “Middle England won’t like you.” We just think: “Can we not just try it – and see what the audience do?””

Like Terry Taylor in Jane Elliot’s experiment, many commissioners would baulk at the idea that the practices that saw fulsome reflections of blackness excised from British screens was in any way racist. However, Angie Le Mar points directly to the reality that she and many other on and off-screen black British talent, myself included, faced. The fallacy that “black doesn’t sell” or doesn’t attract viewership, in this case, plagued commissioning and denied black British people onscreen reflections of their experience. After the end of Joycelyn Essien’s BBC comedy sketch show Little Miss Joycelyn in 2009 it would be another six years until a black British screenwriter would helm a series they created and starred in.

“After Little Miss Joycelyn, it would be another six years until a black British screenwriter would helm a series they created and starred in”

Instead of becoming disillusioned, black British content creators, locked out of the industry, turned to the internet to create the shows commissioners refused to see the value in. Screenwriters Delia-René Donaldson and Baby Isako collaborated with film producers Victor Adebodun and Femi Oyeniran to write, direct and produce a web series Venus Vs Mars. Starring Letitia Hector as the title character, Venus, the comedy about young Londoner looking for love and all the obstacles she faced dating in the capital. Rather than relying on traditional broadcasting to recognise their talent, they looked to the internet to support and affirm their skills as storytellers.

YouTube became the home of black British small screen representation. Series like Leon Mayne’s Brothers With No Game, Samuell Benta’s All About The McKenzies, Shakira Scott’s Unfamous, Cecile Emeke’s Ackee & Saltfish, Katrina Smith Jackson’s Shrink and Joivan Wade and Percelle Scott’s Man Dem On The Wall, led the charge to ensure the legacy of black people’s stories was upheld. These content creators inspired me. Unable to find a way into the industry, I joined my peers in creating a web series; two in fact. Dear Jesus and its spinoff The Alexis Show.

So diverse were the new YouTube content creators The Screen Nation Awards, created by Charles Thompson MBE to celebrate black British talent, were forced create to a new award ceremony to raise the profiles of the young people who’d show initiative by becoming showrunners in their own right. Like the creators of Venus vs Mars and Brothers With No Game, I also have a Screen Nation Digital-is Award. My peers and I will go on to be nominated for BAFTAs, Emmys and Oscars but I will always cherish my Screen Nation award.

Between the end of Little Miss Joycelyn in 2009 and the start of Michaela Coel’s Chewing Gum in 2015, it would be wrong to pretend there were absolutely no scripted TV series starring black people on British screens. To do so would be to erase the work of screenwriters like Levi David Addai and his Channel4 series Youngers and the whole cast of Top Boy. This said, the opportunities were so few and far between for black talent, Britain haemorrhaged countless actors, writers and directors broad to America.

“Black British screenwriters are working on incredible scripted comedy and drama projects that mean that the next five years in British TV will experience a resurgence of black talent”

While Idris Elba has returned to Britain after finding success abroad and set up his production company Green Door, there are other black British actors who may never return. Michaela Coel’s BAFTA wins combined with the international success of Daniel Kaluuya, Letitia Wright and John Boyega shamed British commissioners and forced them to decide whether upholding the status quo was more financially rewarding than investing in black screenwriting talent. The success of Chewing Gum proved that yes if broadcasters spend the money to develop voices, put resources into an advertising campaign and place these series in a primetime slot the British public regardless of their race, will watch and will laugh.

Television development is a long, expensive process that does not guarantee a series that’s been worked on for two, even three years will ever see the light of day. Despite the odds, black British screenwriters are working on incredible scripted comedy and drama projects that mean that the next five years in British TV will experience a resurgence of black talent. It is a combination of the work of the screenwriters who knocked on the doors during the 90s and early 00s and my generation who used technology to create their own doors that mean that the next five years in TV are going to be more representative than they have been.

We wait eagerly for the small-screen adaptation of Candice Carty-Williams’ bestselling debut novel Queenie. Screenwriters like Bolu Babalola, Theresa Ikoko, Lauren Sequeira, Samson Kayo, Akemnji Ndifornye, Daniel Taylor Lawrence, Yolanda Mercy, Caroll Russell, Emma Dennis-Edwards, Bola Abaje, Racheal Ofori, Adele James, Lenny James, Jazmine Lee-Jones (this list is almost inexhaustible) promise that we will finally have British TV series created by black people representing all the different ways in which black people exist and thrive in this country.