Sitting on the hills looking over the temporary city, the sun was setting behind the Glastonbury sign as we savoured the scene and took pictures for our Facebook cover photos.

It felt like the backdrop for existential questions, but it might have just been the hedonism and the delirium of sleep deprivation. At that moment, I felt that Glastonbury might be the most perfect place in the world, and if there were a God, this is what they would create. It made me consider religion for the first time in a long time.

“I remember going to Sunday school and the pastor told us we would go to hell if we celebrated Halloween. There was a cartoon and everything to explain the gravity of potentially dressing up as a ghost and condemning yourself to an eternity of burning. I was so afraid I didn’t celebrate Halloween for a decade. Pentecostal church does not fuck about,” I said as we walked down the hill towards the frenzy of blinking lights and through the crowds, with the sound of JME and Skepta in the distance. Which does beg the very important question: why were we not watching that set?

“Are you religious?” my friend asked.

“Not at all. I’ve got time for it but it doesn’t do for me what it does for others. I haven’t told my family though; it’s one of those things where I honestly believe ignorance is bliss.”

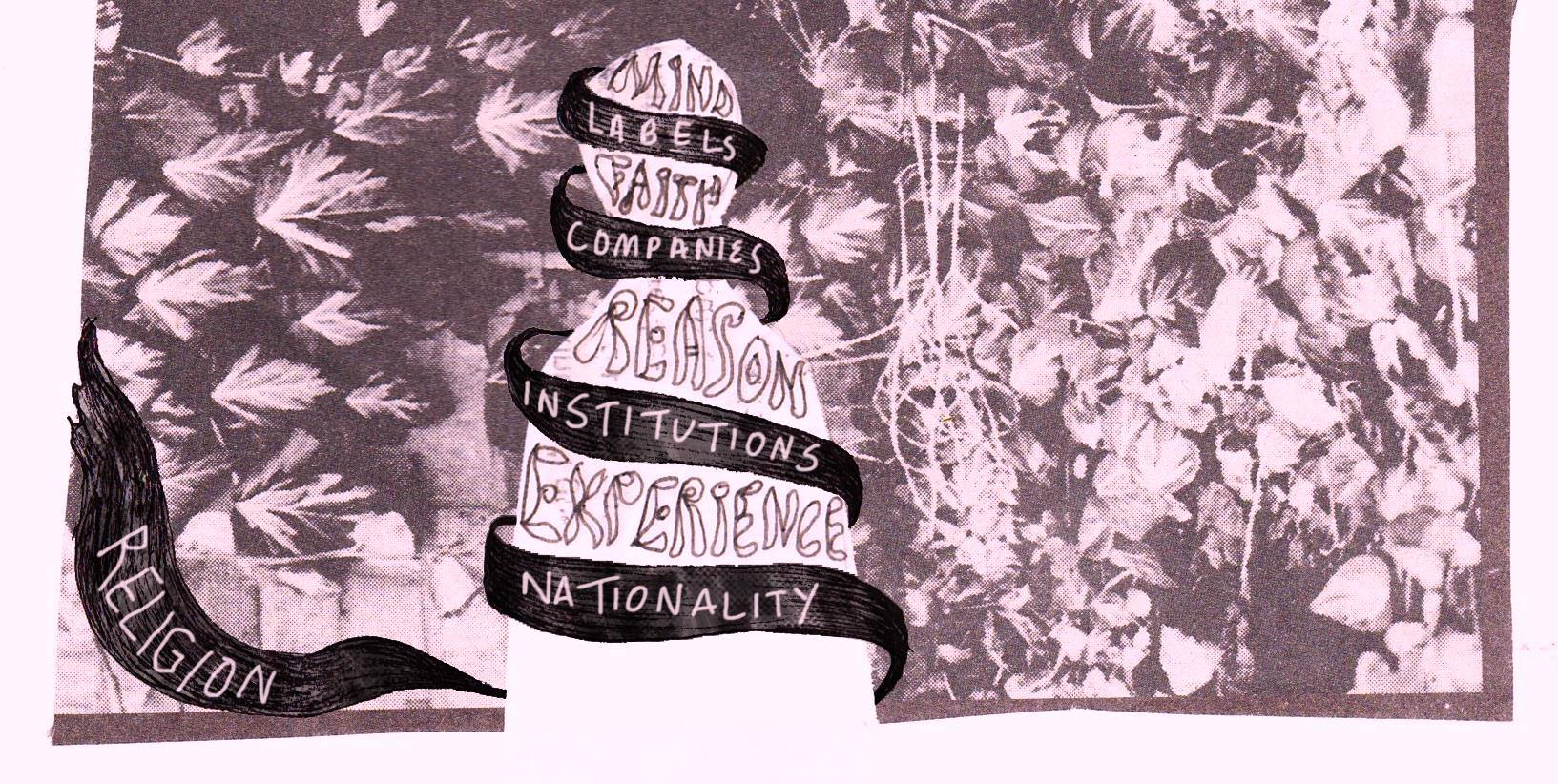

But it’s not really about blissful ignorance; it’s about me not wanting to have a difficult conversation. Because when religion is so intertwined with blackness and identity, questioning the existence of a Christian God makes everything unravel.

My gran was a missionary, so Christianity is no joke in my family but it wasn’t practised in a particularly oppressive way either. After the Halloween incident, I didn’t have to go back to Sunday school for much longer. After all, Sunday school is really a mechanism to get a few hours break from your lovely, but ultimately irritating children.

Christianity though, is something that is accepted and celebrated without question. It is also, particularly with many first and second-generation migrants from the Caribbean, a part of black culture itself. Only the Vatican has more churches per square mile than Jamaica. Black churches were a haven to those arriving from the Caribbean to an otherwise hostile Britain. It was the major driving force behind the abolition of the slave trade but it was also a major vehicle of the colonial project. I don’t have the faith necessary to overlook this.

To reject organised religion in anyway, will be viewed as ‘losing yourself,’ ‘forgetting your culture’ or even being ‘ungrateful to God’, as I try my best on the hot mess journey to configuring my place within the Jamaican diaspora. None of these are conversations I’m rushing to have with my family before Christmas – or maybe ever. I don’t want to face the inevitable disappointment combined with pity for my godless life. But when will it stop? Will I christen my children? Will I get married? If I get married, will there be a religious element to my wedding? How long can I pretend I believe in something?

Whilst researching my dissertation two years ago, I attended the Jamaican Diaspora conference in Birmingham. I took the train back to London with a trainee nurse who had recently moved to the capital. She said she had been struggling, because the girls she lived with partied constantly, drank copiously and were essentially morally degenerate. She had found solace in her church, which she tried to encourage me to attend a number of times throughout the journey. I didn’t know how to tell her that I was in fact, morally degenerate, a borderline alcoholic and prolific partygoer who hadn’t been to a church in five years.

She was talking to someone who climbed out of a window to attend a party just because someone had said she was ‘weak’. As the conversation continued, I mentioned that I often didn’t listen to my father or sometimes, even respect him, because people have to earn such things with their behaviour. Shocked, she replied you should always listen to and respect your parents, no matter what, as clearly outlined in Ephesians 6:1–2. In that moment, I felt more affinity for the degenerate English girls than for the Jamaican nurse, I wasn’t sure how I felt about this and I knew that gran would be turning in her grave.