Ramadan is changing my relationship to wellness and hustle culture

This Ramzaan, I'm reflecting on how my physical health journey has lead me back to my faith.

Mishal Bandukda and Editors

14 Apr 2022

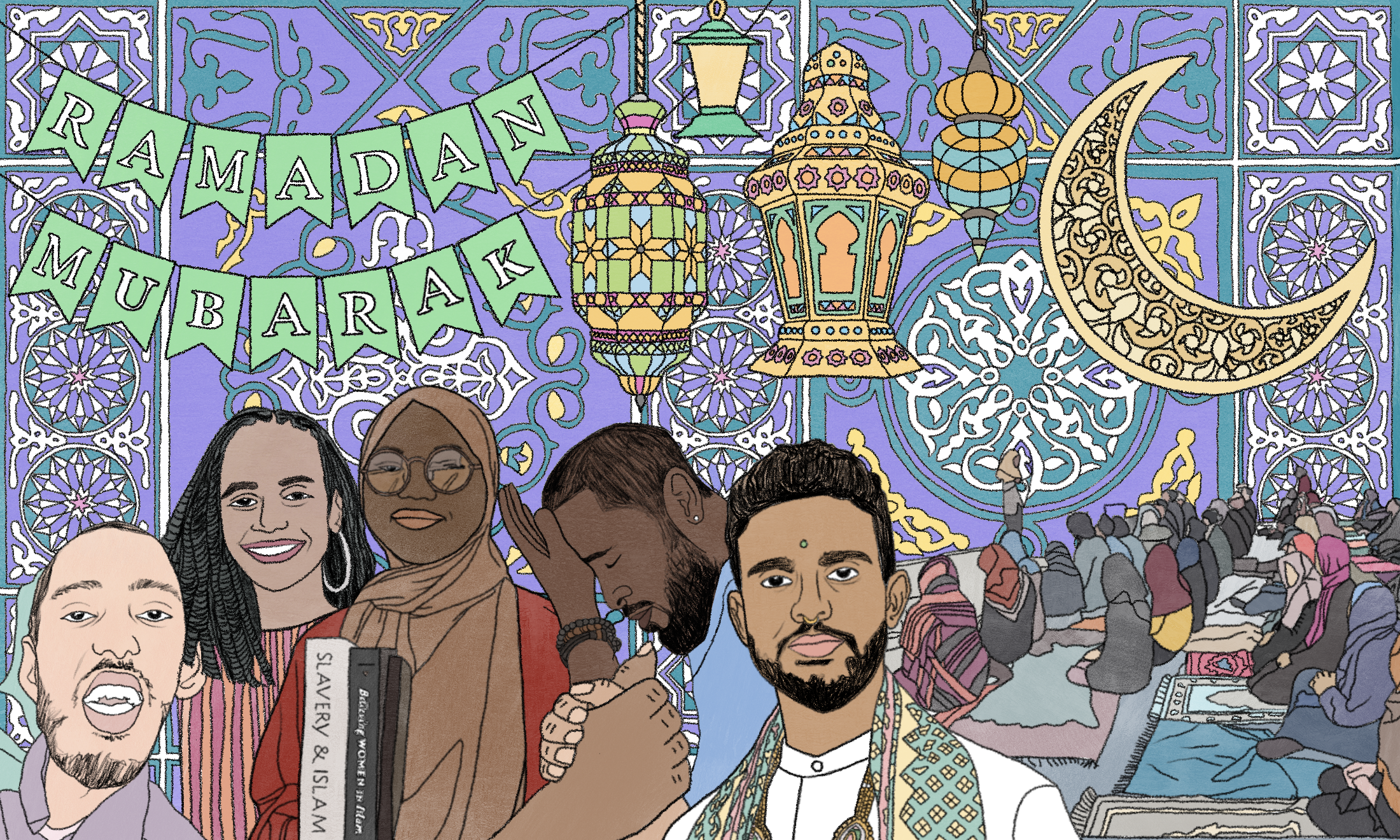

via author

It’s time for Ramzaan (Urdu for Ramadan), and this year I’m fasting for the first time since I was a child. My journey back to this practice has been an unexpected one, but more than ever, it feels like an antidote to the world we live in today.

Many might believe that Ramzaan involves only abstaining from food and water, but for Muslims worldwide, abstinence can include sex or even social media. For me, Ramzaan bears the true meaning of detox, with no overpriced green juices in sight. It interrupts your to-do list and grants you permission to be with yourself for a month, much like a luxury yoga retreat in Bali.

In Pakistan, where I was born and lived as a child, the entire country slows down for the holy period. People take long naps to conserve their energy and it’s common to hear phrases like, “I’ll get back to you when Ramzaan’s over”. It is easy to forget how fragile we are in a world which asks us to prove and perform for our worth constantly; to skip lunch, burn the midnight oil, or feel you have no right to slow down.

Through fasting, you become hyper-aware of your basic physical needs. You’re reminded that you’re human, and that you struggle to function when you are hungry, thirsty or tired. I find that people treat themselves with more compassion during Ramzaan. They recognise that it’s unfair to work their bodies like machines. This reflection has recently forced me to re-examine my relationship with hustle culture and redefine what wellness truly means to me.

“Ramzaan bears the true meaning of detox, with no overpriced green juices in sight”

I realised my relationship to work needed to change at the end of 2021. I had written my first play, a long-term goal of mine. Yet instead of feeling inspired, I was exhausted with the creative ‘side-hustle’ I had taken on in my spare time. I spent my evenings, weekends and annual leave writing, but convinced myself this didn’t count as work. I felt consumed by life, disconnected from my body and tired all the time. I was in need of something that had been absent from my life since I was a child: balance.

My journey to fasting again hasn’t been an easy one. As a teenager, I moved away from Islam and stopped taking part in Ramzaan altogether. My family lived between the UK and Pakistan when I was young, so I inhabited two worlds: an Islamic Republic, where being Muslim is the norm, and England, where it often feels like being an outcast. During my teenage years in the UK, where over 50% of religious hate crimes committed annually are targeted towards Muslims, I avoided talking about my faith out of fear of being judged and excluded.

It’s now been over a decade since I actively engaged with Islam. During the last few years, I’ve struggled with my wellbeing and made many attempts to heal my IBS, social anxiety, burnout and a decade-long binge-eating disorder. From attending classical yoga, to quitting sugar, to following a low FODMAP diet, to paying for a hypnotherapy app, to gulping down self-help books on the commute, I truly believed there was a wellness hack out there that could fix me. I am far from alone in this. What I didn’t expect, however, was that the journey to deal with my physical health would lead me back to my faith.

“The ancient spiritual practice of abstinence has also challenged the workaholism I have recently subjected myself to”

The penny dropped when I recently came across a suggested solution for my IBS: intermittent fasting. After reading about intermittent fasting, and its digestive health benefits, I was struck by how familiar this practice was to me. This prompted me to think about the reasons for fasting in Islam beyond sacrifice and personal endurance. I had observed members of my family using Ramzaan as a form of detox for years; emerging on the other side of the holy month feeling both physically and mentally cleansed. If I could draw parallels between Ramadan and intermittent fasting, I wondered how else Islamic practices might seek to address contemporary concerns faced by society today.

This Ramzaan I’m engaging in prayer five times a day; a form of mentally checking in with myself at regular intervals. I can see physical parallels between praying and other practices I use to enhance my wellbeing, namely yoga. I experience similar mental clarity during my prayers to when I practise yoga, with both requiring me to slow down and connect to my body while performing a series of movements. A mindfulness emerges from the repetitive nature of reciting the prayers, which are always the same verses of the Qu’ran. Praying in Arabic used to feel alienating when I was younger, but now it encourages me to focus on how the words sound, which has become a welcome break from over-thinking.

“Ramzaan is teaching me that what I need to be well doesn’t exist ‘out there’; it isn’t a hack I haven’t found yet, but rather the ability to turn inwards, away from the false promises of consumerism”

The ancient spiritual practice of abstinence has also challenged the workaholism I have recently subjected myself to. I’ve cancelled plans, knowing I’ll be too tired to enjoy myself after fasting. I take the utmost care when selecting what to eat in the morning, knowing that I need to feel full and energised for as long as possible. In the evening, I treat myself to a scoop of ice cream to congratulate myself for making it through the day. I’m challenging the image of wellness I had in my mind, one of punishment and restriction, and replacing it with moderation and compassion. Ramzaan is teaching me that what I need to be well doesn’t exist ‘out there’; it isn’t a hack I haven’t found yet, but rather the ability to turn inwards, away from the false promises of consumerism, and trust that I already know how to take care of myself.

I’m also reading the Qu’ran in English for the first time because I want to understand its relevance to my life today. One verse spoke to me in particular: “And it is thus We appointed you to be the community of the middle way” (Chapter 2: Verse 143). The translator suggests that this is the very essence of what it means to be Muslim: to follow the ‘middle path’. Islam invites us to seek balance in all aspects of our lives, not as a suggestion, but a spiritual obligation. After several years of denying my faith, I feel grateful to have Islam in my life. I hope that the rest of this Ramzaan will allow me to deepen my understanding of what it means to live a balanced life in a world of harmful extremes.