Nayrouz Qarmout wants you to know about struggle and self-discovery in Palestine

Diana Alghoul

27 Sep 2019

Image via Nayrouz Qarmout

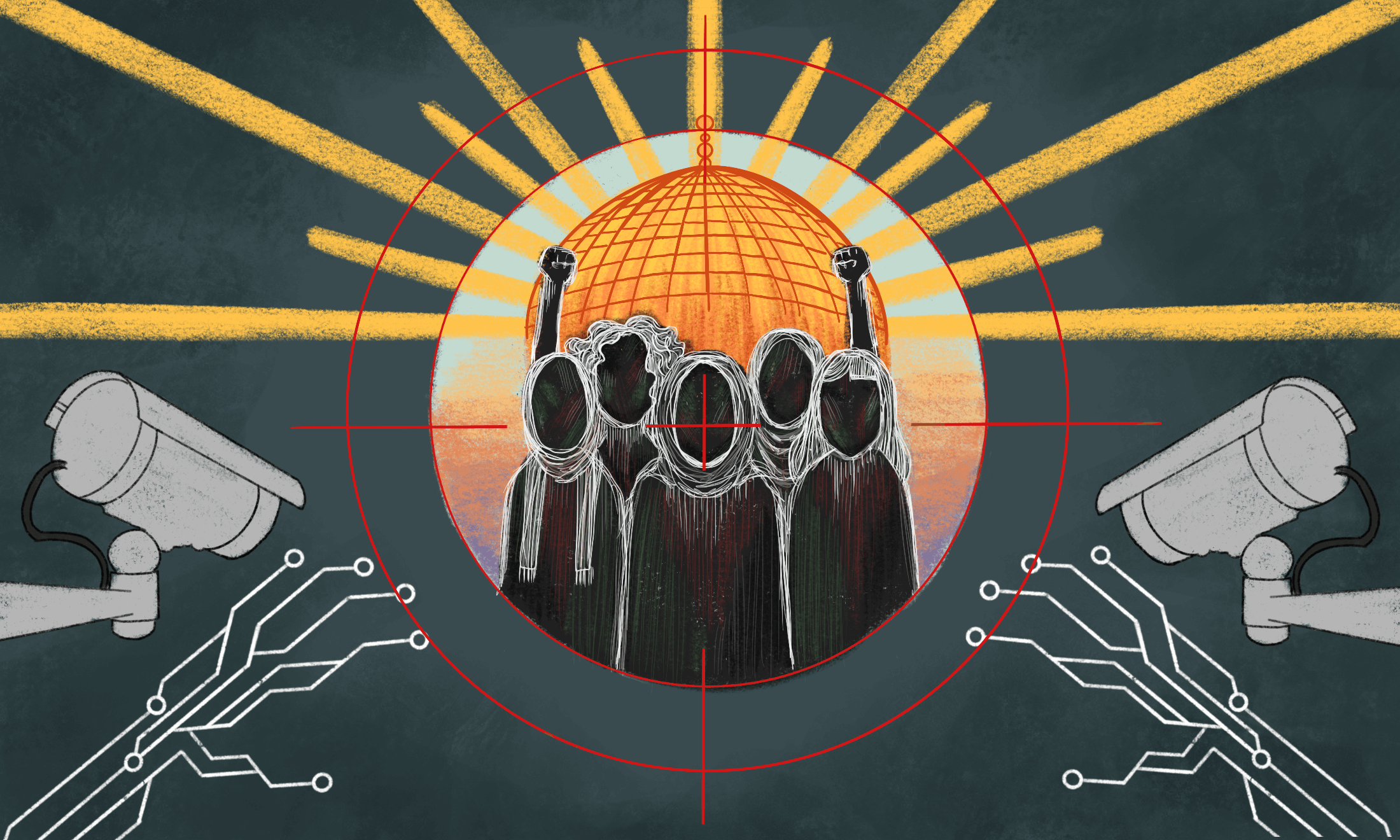

Nuanced discussions about Palestine in mainstream media are few and far between. Palestinian activists who are leading the struggle for liberation are commonly smeared as terrorists and anti-Semites. Often, Palestinians are described as an uncontrollable Arab population that needs to be contained by Israel’s punitive measures, for the sake of national security. However, the feelings and perspectives of actual Palestinian people are often absent from these discussions. The Sea Cloak, a new collection of 11 short stories by Nayrouz Qarmout, seeks to redress this silencing, by shining a light on the human experience behind the conflict.

Nayrouz is a Palestinian woman who grew up in a refugee camp in Syria and was later returned to Gaza as part of the 1994 Oslo Peace Accord. She has remained in the besieged territory and now works in the Ministry of Women’s affairs. In her writing, Nayrouz champions women’s rights and highlights the plight of not just being a Palestinian enduring the complex layers of Israel’s occupation, but doing so under the watchful eyes of patriarchy. She aims in her writing to encourage the global discussion of Palestine to incorporate much more nuance, by highlighting the Palestinian plight through the lenses of culture and humanitarianism.

Showing the many faces of Palestine

In the first story of the collection, Nayrouz describes the experience of a young girl living in Gaza, wanting to break free from traditional norms. The story is set in the context of the rise in popularity of Hamas, a Palestinian Islamist political organisation, in the 1980s. This era brought with it a surge in traditional sentiments in Gaza, which meant that girls and women were increasingly forced to adhere to conservative social and political attitudes.

Hamas was established out of the Islamic charity al-Mujama al-Islamiya, which was formed in 1973 as a social hub offering food and healthcare to effectively bring Palestinians back to Islam. The group was led by Sheikh Ahmed Yassin, who then became the spiritual leader of Hamas, when it was established 14 years later. Al-Mujamaa al-Islamiya had several campaigns that deliberately targeted women, including promoting wearing the hijab. By the late 1980s, it was seen as almost taboo for women in Gaza to not have at least one form of headcovering.

Hamas continued the legacy of al-Mujamaa al-Islamiya in policing women — especially after the group took control of Gaza in 2007. In 2009, Hamas police attempted to detain Palestinian journalist Asma Alghoul because of how she was dressed, and for behaving “unislamically” at a beach. She was wearing a t-shirt and jeans and was laughing out loud in a mixed-gendered friendship group.

“Nayrouz takes the reader through a story of a young girl finding freedom in Gaza’s sea”

Nayrouz takes the reader through a story of a young girl discovering her individuality as she begins her journey to womanhood; finding freedom in Gaza’s sea. Before the siege, Gaza was known for its mesmerising coastline and the Gazan people has an important connection to their beaches. In the story, not only does the sea represent endless opportunity, but reminds readers of this part of Gaza’s unique geological character which doesn’t usually hit the headlines.

Hamas isn’t mentioned explicitly in the story, nor is the broader political context of the conflict. The story focuses on the young girl, and the effects of the siege are described through her eyes. The general attitude of conservatism which characterises the region is shown through its impact on her world, such as girls and boys not being able to play together, and getting sent home from playing and being told to wear a hijab when her family decides that she is starting to “come of age”.

Nayrouz is from Gaza, but in the stories she also explores other parts of the Palestinian experience. She describes the different threats and challenges faced across the region such as people living in the occupied West Bank who have their livelihoods threatened by the expansion of Israel’s illegal occupation. The surge in building of illegal settlements means that Palestinians are constantly faced with the reality of potentially losing their homes to demolitions, expulsions and tunnel building underneath houses which destroy foundations, as is currently happening in the occupied East Jerusalem neighbourhood in Silwan. West Bank Palestinians have to deal with Israeli settlers thriving on their impoverished land on a daily basis.

Another story in the collection – ‘Black Grapes’ – illuminates this reality perfectly. It follows the story of a Palestinian man in occupied Bethlehem working on an Israeli grape farm in the illegal settlement of Efrat. The story explores his interactions with Israeli people — including his customers and boss– who discriminate against the farm worker on his own land. The story contains a series of twists: the farm worker faces casual racism from an Israeli customer, and is initially defended by his Israeli employer. However, the layered relationship between the two takes a turn when his employer later becomes his oppressor by depriving him of his rights.

“The complex relationship Palestinians have with settlers is apparent in Nayrouz’s storytelling”

The complex relationship Palestinians have with settlers is apparent in Nayrouz’s storytelling – on the one hand, settlers are complicit in the systematic erasure of any prospect of a Palestinian state, but on the other, human interactions on a personal level are more complex, and Nayrouz gives her characters agency within an oppressive context. The Palestinian farmworker is both defended and oppressed by his employer, but the over-arching environment is one in which he is dependent on an illegal settlement business to feed his family.

The oppressor in action is also shown in ‘White Lilies’, where the parallel realities of an Israeli drone operator and an Palestinian child are explored. The story reflects on the innocence of a Palestinian child watching an Israeli drone, whilst the operator in Tel Aviv aims to hit close by. The stark power-differential between the two characters is made clear; the child’s life depends on whether or not the man she doesn’t know in Tel Aviv pushes a button.

Subverting and re-making traditional story-telling

In Arabic story-telling, traditionally the writer or speaker puts most of their effort into giving the reader a sense of the scene in which the story takes place through close attention to minutiae and small details. One of the most famous examples of thisis the work of Palestinian writer and leading member of the Palestinian Marxist movement Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), Ghassan Kanafani. In his 1962 novel Men in the Sun, Ghassan takes care to describe the Palestinian land he is standing on – a symbol of nationalism and a pressing thought in every Palestinian’s mind, even if they aren’t physically in the country.

Because of this, a book of short stories in Arabic (as The Sea Cloak was originally written) is relatively unorthodox, especially because short stories only became popular as the printing press reached the Middle East in the 1870s. Rather than listening to long-winding stories that are staple to Bedouin Arab tradition, short stories were originally written for upper-class Arabs in newspapers.

The Arabic language is traditionally a language to be heard, rather than read, and so story-telling in Arabic generally emphasises scenery, especially because Bedouin Arabs had little access to visual aids in storytelling. Egyptian scholar Hussayn Fawzi describes the tradition as an essential tool which showed listeners and readers how Egyptian history was so essential to civilisation — something which he said would have been impossible to show on a cinematic scale across all socioeconomic classes before 1952. Nayrouz suberts this approach: rather than focusing on scenery before telling the story, she often describes the scene through the experience of characters.

Tales that humanise a conflict zone

Because Nayrouz’s stories lead with emotion and character, The Sea Cloak is a book anyone can pick up regardless of who they are and how much they know about Palestine. For allies who understand the situation in Palestine, the short stories illustrate an emotional dimension of what readers might already have learnt through news reporting and commentary on the conflict. For those who aren’t as well versed on the occupation of Palestine, the book is a unique tool of learning about the Palestinian experiences through human narratives, as opposed to cold statistics.

For Palestinians, the stories are a strong reminder of the emotional scars that come with occupation. In a context in which mental health care isn’t prioritised or euro-centric models and framings of mental health inaccurately describe, for example, the impacts of constant bombardment and living in a war zone, Nayrouz’s writing validates the diverse complexities of feelings that make up the Palestinian experience.

Reading this book is a reminder to Palestinians in the diaspora about how it feels to live under occupation. The Sea Cloak seeks to humanise a conflict which often feels out of reach and brings home human stories which encourage re-finding an emotional connection to the land. Nayrouz’s tender, moving, and confrontational writing is a reminder that it’s important to not just know but to feel.