Annette Bernhardt/Wikimedia Commons

Only by abolishing colonialism will Palestine be free

In an extract from her new book, Nada Elia explains why activism must be decolonial and intersectional to secure the future of Palestine.

Nada Elia

02 Feb 2023

It is impossible to overemphasise that today’s activism must be transformational. It must be decolonial, seeking full liberation from the mental and generational shackles of the oppressive system, and not merely anticolonial, aimed at ousting the occupier. Achieving justice for Palestine entails more than abolishing Israeli apartheid. The inertia of over a century of inequality, and of the privileged status of the settlers as they forcibly and violently dispossessed, and continue to dispossess, Palestine’s Indigenous people, cannot be reversed solely through the formal dissolution of the oppressive system.

The present plight of formerly colonised countries around the globe, after they gained their independence, as well as the ongoing circumstances of the Black and Indigenous people of North America, who theoretically have equal rights but who have remained criminalised, hunted, caged, and murdered, is proof that eliminating legal barriers without addressing the practical consequences of injustice does not redress historic inequities. Therefore, even as we are organising to overthrow Israel’s state-sanctioned violence, we must look beyond apartheid as the primary means of oppression of the Palestinian people.

Beyond apartheid, Zionism itself must be abolished. It is an essentially racist, supremacist ideology, and the oppressive system it has produced cannot be reformed. Abolition hinges on the understanding that reform – making changes to an existing system – does not solve the problems created by that system, it only helps maintain the system by making it less obviously abrasive, without transforming its corrosive core. Today, this argument is being made about the police all across the US, with a number of grassroots organisers and public intellectuals debunking myths that the police are an overall positive social force, where rogue elements occasionally go awry.

“In the context of Palestine, abolition hinges on the understanding that a reform of the Zionist state cannot possibly solve the problems created by Zionism, it only helps maintain them”

Abolitionists argue instead that the system is not broken, it is functioning exactly as it was always intended to. Therefore, there is no need to “fix” it, to restore it to its original form, because that form itself is oppressive at its inception, as it remains to this day. When was “the system” not broken, abolitionists ask? When was it not racist, when was it not violent, when we know that the origin of the police forces in the US south was as slave patrols, while in the US north, they were first established to thwart protests for better labour conditions? The call for abolishing the police, and prisons, is not recent, having been discussed in the US, for example, almost 20 years ago by Angela Davis in Are Prisons Obsolete? and by anti-carceral grassroots groups such as Critical Resistance, and INCITE! Feminists of Color Against Violence, who understood that their communities are endangered, not protected, by the “security state”.

However, abolition has now entered popular discourse, with organisers demanding at protests nationally that police forces be defunded, and the abolitionist Mariame Kaba writing an op-ed published in The New York Times titled ‘Yes, We Mean Literally Abolish the Police‘. Police abolitionists are very clear about the necessity of building strong structures to support disenfranchised communities that have never been “served and protected” by the police. As Angela Davis writes: “Abolition is about organising community alternatives to policing and mass incarceration, about using the breathing room afforded by these small victories not to propose a slightly better version of the same, but to shoot for something radically different.”

In the context of Palestine, abolition hinges on the understanding that a reform of the Zionist state cannot possibly solve the problems created by Zionism, it only helps maintain them. Seeking to reform the Zionist state assumes that Zionism’s initial impulse – which is premised on settler colonialism and necessitates land theft, dispossession, displacement, human and cultural genocide – is acceptable, but that something went wrong, somewhere down the line.

For instance, a reform limited to the West Bank and Gaza implies that al-Nakba – Palestine’s catastrophe – did not start around 1948, but in 1967. Ending the occupation of the West Bank and Gaza Strip would not dismantle Jewish supremacy in those parts of the Palestinian homeland first occupied in 1948; nor would it address the Right of Return of Palestinians displaced from those cities and villages occupied in 1948, without which the Zionist dream would not have materialised. Indeed, the “peace process”, with its endless round of futile talks, is an illustration of the attempt at “reform”, rather than abolition.

What that process has led to is an entrenchment of dispossession, now subcontracted to the Palestinian Authority. Instead, one must ask: “When was Zionism not a supremacist ideology privileging some people over others, based on perceived ethnicity? When did Zionism not necessitate the ethnic cleansing of the Palestinian people? Was there ever one brief moment, from its inception to the present day, when Zionism was not violent?” Zionism cannot be reformed; it must be abolished.

And abolition in the context of Palestine, as in all contexts, also presumes that one is working to set up the alternative at the very same time one is dismantling the oppressive system. The many initiatives developed by Palestinians today are radically different from what governments have been proposing and supporting since before 1948. Farmers are already establishing sustainable, community-supported agriculture. Educators are crafting liberatory and inclusive curricula. Feminists are setting up the infrastructure for a post-Zionist society that is also post-patriarchal. Public intellectuals are crafting detailed proposals that rise above partitions and borders. And Palestinians, both in the diaspora and the homeland, are forming global alliances around causes that bring us together, rather than set us apart.

“By looking beyond apartheid, and beyond Zionism, we can start envisioning the future of Palestine, one that is beyond various binaries”

This book discusses some of these while exposing the irreconcilability of Zionism with justice, sustainability, feminism, liberation. By looking beyond apartheid, and beyond Zionism, we can start envisioning the future of Palestine, one that is beyond various binaries, whether these be the obsolete “two states” delusion, or the “homeland” and the “diaspora” division, or even “Jews” and “Arabs”, as if these were mutually exclusive, rather than a colonial invention. Historically, these binaries have been used to divide, yet they have also always had inherently blurred boundaries and criteria. This is evident in the fact that even fourth-generation Palestinian refugees, whether in the Gaza Strip, or in Seattle, Washington, always recall the city or village their families were displaced from.

Moreover, a refugee from Yaffa in present-day Israel, would not be “returning” to their hometown if they were to move to the West Bank, where the new state of Palestine is to be located, according to the ever elusive “two-state solution”. Nor would someone from Haifa be “returning” to Khan Younis, in the Gaza Strip, also envisioned as part of that new, amputated Palestine. They would still be displaced, denied the right to return to their homes. Palestine has historically existed as the land between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea, and partial liberation is not justice denied, it is, quite simply, impossible. This is why, following decades of governments and politicians attempting to establish an independent Palestinian “state”, Palestine’s public intellectuals and activists are looking outside the framework of a two state solution, to explore nationhood in the context of decolonisation, instead of state building. This is the transformative vision that accompanies abolitionist calls, and which we are already witnessing among Palestinian feminist organisers.

A new form of activism

From Gaza to Ramallah to Haifa, to New York City and Oakland, California, as a people, we Palestinians are united in our yearning for liberation. Yet, for those of us living in the Global North, we have also joined ranks with other racialised, marginalised, and oppressed communities because our circumstances align us with the surveilled, the criminalised, the disenfranchised, the communities seeking to make this world a better place for all of us, not just a good place for the privileged few.

In today’s rapidly evolving context, it is imperative that organisers and activists tend to the many fronts simultaneously, and intentionally, so as to set the foundations for a future Palestine that avoids the trappings of the always-struggling postcolonial nation states of the 20th century. Black solidarity with Palestine is longstanding, having found its clearest expressions during the Civil Rights movement, when the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the Black Panthers, Angela Y. Davis, Malcolm X, Kwame Ture (formerly Stokey Carmichael), Audre Lorde, June Jordan, and Muhammad Ali, among many others, supported the Palestinian people, while African leaders from Nelson Mandela to Kwame Nkrumah also supported Palestinian liberation.

More recently, Black-Palestinian solidarity has been injected with renewed energy in the wake of the hyper-militarisation of US police, the latter being due in no small part to their joint training with Israeli security forces. And a recent statement by The Red Nation collective opens with the assertion that “Palestine is the moral barometer of Indigenous North America”. Meanwhile, Palestinians in the homeland and the global diaspora are actively educating themselves about the struggles of Black and Brown communities around the world and sending tips on confronting police violence from the Gaza Strip to Ferguson, Missouri.

“We must practise decolonisation in scholarship and discourse, as much as in natural resources such as land and water”

In this book, I explore the hopeful arc of this new type of activism, as I discuss how today’s intersectional, joint struggles are paving the way to a dignified life for all. As I challenge the dominant discourse on the question of Palestine, I also intentionally ground my analysis in the writings of grassroots organisers in the USA, as well as the many stellar Palestinian scholars, activists, and organisers who have carved out the space for this discussion. Many of my sources are also Palestinian, rather than from the Global North, even when the latter are available.

In an era where we rightly want to hear primarily from queer, and/or Black, and/or Indigenous peoples about their lived experiences, the plight of the Palestinian people remains one of the few instances where observations by outsiders are considered more valid than inside knowledge and scholarship. This is not to dismiss the value of some important contributions by non-Palestinians, but hinges instead on my conviction that we must practise decolonisation in scholarship and discourse, as much as in natural resources such as land and water.

Just as the Western narrative has long dominated the discourse on Palestine, so have non-Western voices been valued in the West over the voices of Palestinians, who should be the ones articulating their own experiences, analysis, and hopes. This is especially the case in writings critical of Israel, where Jewish allies who denounce Israel’s crimes are given more prominent platforms than Palestinians who resist and survive Israel’s crimes. The valuing of allied scholarship over Indigenous knowledge is passé, and should be stopped, and reversed, just as colonialism itself must be stopped, and reversed. And the myopic denunciation of the micro level of gendered violence, which would look at “conservative Arab culture” but not at the broader level of gendered violence of settler colonialism, is no longer acceptable. Finally, to marginalise the analysis of women’s contributions in an “accessory” chapter, rather than as part and parcel of our collective sumud and the beacon of our full liberation, is no longer admissible.

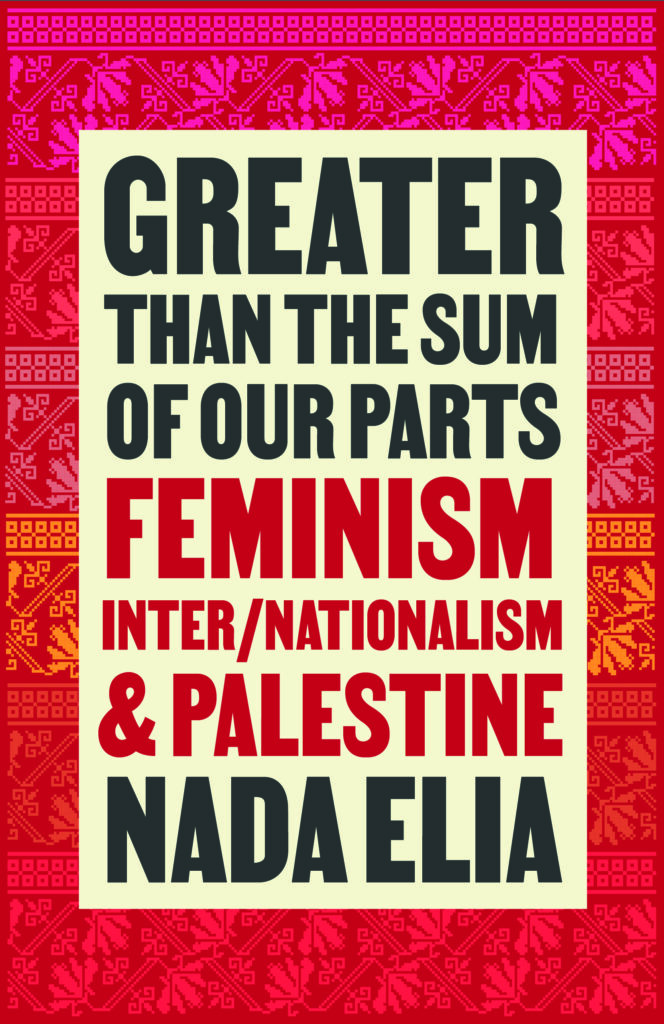

Greater Than The Sum Of Our Parts: Feminism, Inter/Nationalism and Palestine by Nada Elia is a new book published by Pluto Press, available for purchase here.

The contribution of our members is crucial. Their support enables us to be proudly independent, challenge the whitewashed media landscape and most importantly, platform the work of marginalised communities. To continue this mission, we need to grow gal-dem to 6,000 members – and we can only do this with your support.

As a member you will enjoy exclusive access to our gal-dem Discord channel and Culture Club, live chats with our editors, skill shares, discounts, events, newsletters and more! Support our community and become a member today from as little as £4.99 a month.