Photography by Micha Frazer-Carroll

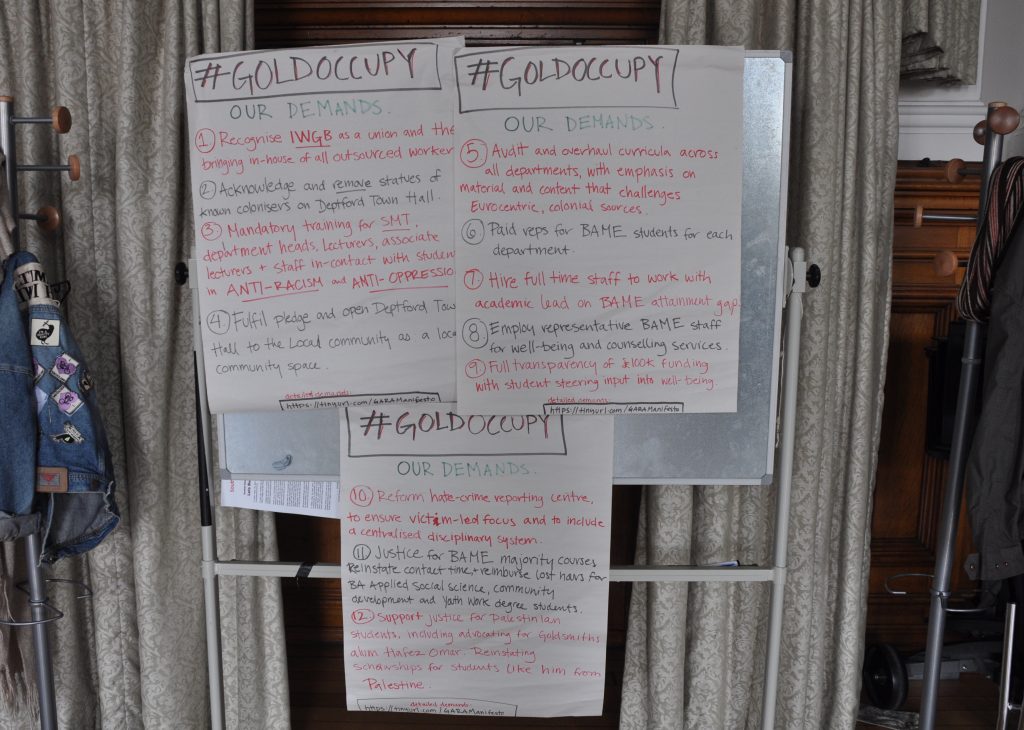

After 137 days in occupation, students of colour at Goldsmiths have won a long, gruelling fight against their university – marking what can only be described as a momentous achievement. The group’s demands, which the university has now agreed to meet, were extensive; including requesting that the university investigate the possibility of colonial reparations, reinstate scholarships for Palestinian students, launch an institution-wide plan to tackle racism at the university, introduce unconscious bias training for members of academic staff, issue an audit of the curricula, address statues of colonisers, and ensure training and investment for culturally competent counselling services, to name a few.

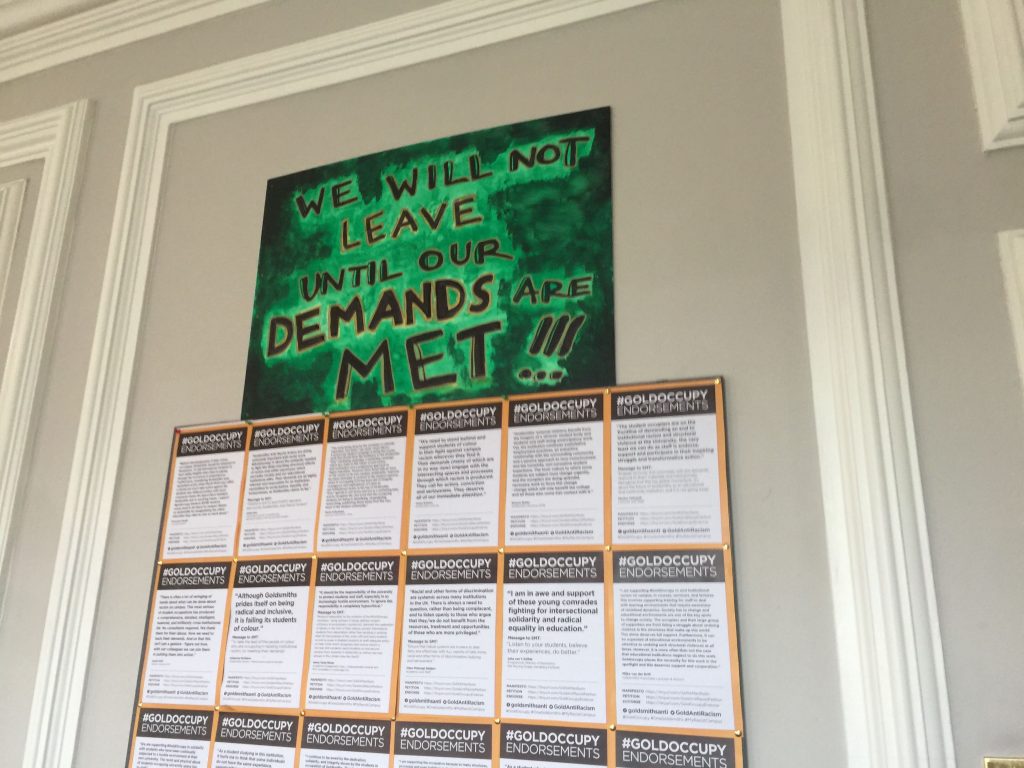

Fiona, a second year anthropology and media student, had previously told me that as far as they were concerned, it was “all or nothing” – the students wouldn’t leave the university’s administrative centre until their demands were agreed to be met. Even though the university pursued legal action against the students, with a court hearing taking place in the week before the occupation ended, Goldsmiths’ Senior Management Team (SMT) did eventually sign a legally binding document to commit to their demands.

“What we’ve done in four months, others could not do in four years”

I visited the occupation for the second time on day 136, the day before Goldsmiths put pen to paper. When I arrive, I walk straight past security and up the stairs. Back in my first visit in April, there had been a little interrogation about who I was here to visit, but by now, it feels like the guards are used to the revolving door of students, journalists, and members of the local community wanting to in some way be involved with the group’s historic anti-racist action.

When I was first looking into this story, I was struck by how much Goldsmiths Anti-Racist Action (GARA) had demanded. Their Google Doc manifesto read like a comprehensive list of systemic racial injustices that not only were deeply entrenched within the university, but extended into wider racist structures in the UK and beyond. But what struck me most about the demands is that many were costly – so getting the university SMT to agree to them was all the more impressive.

“What we’ve done in four months, other people could not do in four years,” Nishat, a first year sociology student tells me.

Sara, a co-organiser, who’s also sitting with us in the grand mint-green boardroom around a comically large meeting table, agrees. “The university took decades to address these issues – not even to work on them – just to address them,” she says. “But within the last four months we’ve had 10 out of 12 demands met. A lot of people did not expect that in the first week. People also looked at our manifesto and said we were asking for too much – but how can we ask for too much when we’re paying £9,250 for a university where most of our lecturers are racist?”

It makes a lot of sense when Sara puts it bluntly like this. It can be easy to question whether what you’re asking for is reasonable, or even feasible. But GARA were raising completely valid concerns, particularly with regards to racism in their teaching environments, including microaggressions like lecturers allegedly reading out the n-word. And after causing enough disruption, they had clearly got the university to acknowledge that too – at which point pots of money seemed to magically appear.

“If this university cared about students’ mental health, they would never threaten to call bailiffs or police on students of colour”

On the day we talk, GARA have already successfully got the university to agree to 10 demands in writing, and verbally during a draining 10-hour meeting, but a legally binding contract hasn’t been signed yet. Nishat and Sara explain why this is so crucial.

“We won’t leave until we have a signed contract,” Sara says. “We know from history that Goldsmiths has gone back on their promises. They did it when they revoked their Palestinian scholarships 10 years ago, they did it when they removed community access in 2004, so we’ve seen time and time again that we cannot trust this institution. That’s why we need something legally binding.”

Insidious, institutionally-embedded racism appears to have tinged every element of the group’s interactions with the central university. On my first visit, John, a third year music and computing student, claimed they were racially profiled by security, and Sara and Nishat posit that SMT’s behaviour during the 10-hour negotiation meeting was similarly racialised.

Photography by Micha Frazer-Carroll

“They were still tone policing us, claiming we were personally attacking them when the only reason we were really addressing specific members of SMT was because the demand in question was under their remit.” She admits that in the end the ordeal drove her to tears.

Sara adds that the emotional labour expended by students of colour, and the way it can take a toll on students’ mental health, went over the SMT’s heads. “I think they’re completely detached from how this all really affects us, and is a part of our everyday life. Students of colour currently have a risk of ending up with a criminal record,” she explains. “We laid out our trauma for them in that 10 hour meeting, but they left that meeting and then still called the police.”

She continues: “It’s like this university talks about mental health, but that’s false – if they did, they would never threaten to call bailiffs or police on students of colour.”

In a statement to gal-dem, Goldsmiths said they were “pleased” that Deptford Town Hall, a “vital teaching space” would be ready for the start of the academic year in September. They added: “We have listened to the issues raised by the protesters and committed to a comprehensive action plan addressing issues of racial justice and will be working hard to improve the experiences of our BME students and staff.”

The struggle to obtain a simple signed legal document was certainly intense. The occupation spanned exam term, and Nishat claims that a number of students had to defer their exams or even repeat the year because of the emotional toll of protesting against the university. Despite this, what they have achieved really does feel quite staggering; and it makes me wonder what it means for the future. GARA have made clear that the occupation has ended, but the group has not. And more broadly, it’s worth asking: if a cluster of ordinary students of colour can reclaim a university building and overhaul dozens of structures, policies and funding streams at Goldsmiths – is this possible elsewhere?

“Whatever other students of colour want to change within their institutions, it can be done. We are the proof”

“We all know this is not just a Goldsmiths issue,” Nishat says. “For all HE institutions across the sector, I hope we can be an example for other students to show that it’s achievable, and what we’ve done can be replicated elsewhere.”

And this has been evidenced in the solidarity and support they’ve had throughout the occupation, but also the guidance they have been able to provide to other student organisers. “We’ve already been in contact with John Hopkins University, who were also occupying for a while at the same time as us. That was in Baltimore in the US, and it was amazing that we had a link with them where we could Facetime them two or three times a week, and discuss our respective situations.” As a result, the support GARA had was international, as well as dozens of UK universities issuing statements in solidarity. The example set by their organising will also, hopefully, have lasting repercussions.

Photography by Micha Frazer-Carroll

I ask Nishat what she would tell other students who want to challenge entrenched racism within their institutions. She pauses. “Whatever it is that other students of colour want to change within their institutions, in terms of making it a more survivable and functional environment for them, it can be done. We are the proof.”

“At all times we have to be prepared to challenge institutions, and their complicity in racism. And it changes you. Myself four months ago, and myself now are completely different people – and that’s purely the experiences I’ve had in here, and learnt on the job.”

“One thing I’ve learnt through all this is that you have more power than you realise.”